This year, The Cold Magazine travelled to Geneva to attend the HEAD Genève Fashion Show: a major showcase of emerging talent, supported by industry-leading partners and a jury of notable figures across global fashion, including Louis Vuitton, Maison Margiela and Vogue Runway. Across both BA and MA programmes, the work felt unequivocally individual. What a cohort we had! These designers questioned everything, from construction to silhouette. I left Geneva electrified by the scale of innovation on display and full of excitement for what’s coming next.

In the following feature, we spotlight ten graduates: every MA designer and each of the prize-winning BA collections. (We also sat down with Matil Vanlint for a separate in-depth article on her collection, V*, which you can read here.) This selection represents just a fraction of the talent showcased this season (23 BA students and 8 MA students in total!) but together they offer a glimpse into what makes HEAD Genève such an essential space for fashion today: a school with serious technical facilities, tutors who invest deeply in individual creative paths, and a group of students whose collaborations generate truly extraordinary synergies.

Here, ten of HEAD Genève’s most exciting emerging voices speak directly about their collections, their materials, their experiences and the worlds they’re building next – our hopes are high for this lot.

Vincent Delobelle, Longing or Belonging (MA)

What inspired Longing or Belonging?

This collection is rooted in the experience of moving through the world as a class defector – navigating spaces where you’re not expected. For a long time, I felt that longing: hoping someone would extend a hand and silently say “yes, you’re allowed to be here.” But eventually I realised that belonging doesn’t come from someone else validating you; it comes from the act of dressing yourself on your own terms. It’s an attitude, a form of self-invention. Through fabric manipulation and handwork, you create your own space rather than waiting for access to someone else’s.

How did collaboration and process shape the collection?

The collection blends couture archetypes with upcycling, experimentation, and handwork done with friends. The process became its own community – embroidering, transforming scraps, building identity through touch and repetition. It was about performing confidence even when we didn’t feel we had the right to, acting like superstars when no one would ever call us that. Some of the strongest looks came from humble materials. One of the most dramatic dresses – the long white silhouette – was originally made from just three tiny bobbins of thread. We crocheted it by hand, creating a couture texture from almost nothing. The feather-covered helmet captures the transitions of moving between worlds: how the mundane can be elevated, how you rewrite expectations with humour and audacity.

How did HEAD Genève support you in this exploration, and what’s next?

My experience at HEAD was defined by freedom. Sometimes exhilarating, sometimes terrifying. The tutors don’t give you a mold or a formula; they place you at the center of your own process. That mix of liberation, responsibility and trust forces you to articulate your vision and build your own language. As for what’s next… everything is moving very quickly. The show was on Friday, and on Saturday I moved to Paris! I’m focusing on internships and collaborations. It feels like the beginning of something, and I’m ready for whatever comes next.

Clémentine Lejeune, Apparence Fragmentée (MA)

What was the starting point for your collection?

My collection was trying to dissect the emotions and entities that construct our appearance. It was a long process questioning our rapport to our own appearance and subjectivity and how clothes and accessories impact our construction. The aim was to figure out the fundamental link between materiality and consciousness. I try to reflect my own feelings about clothing and being dressed, like desire, vulnerability or delicacy, but also the entities that take parts of this process as heritage or affinities, so the most important part for me was to find textures that relate theses entities, by using pleats, coating fabrics or developing organic pattern. I think it was like developing my own fashion vocabulary and I really enjoyed that!

How did you explore expression and ornament in the garments?

I was thinking a lot about “outrance” – in Baudrillard’s words, “saying too much to say it right.” I had so much pleasure realising my garments, and reconciling myself with my affinities like historical costume, rich textiles, or old jewellery.

How did the HEAD Genève environment support that exploration? And what comes next?

The Master at HEAD was a beautiful space to experiment around my subject. I was always supported by my friends and helped by professors who were aware of my subject and my sensibility. It permits me to express something that looked so confusing at first, and finally to feel totally free to find out more.

For now I want to do some internship to discover the fashion world, like in Julia Heuer studio for now, but I really want to continue my research around appearance, clothes and subjectivity. The next step could be a phd or some residences to think about all these elements introduced during my master.

Noa Toledano, Everything Sinks But The Kitchen (MA)

Jewellery made in collaboration with @meryldegez

What inspired Everything sinks but the kitchen – both the title and the collection behind it?

This project started with a question: how can you accept yourself in the in-between, when you come from a culture that isn’t dominant and you evolve differently from it? My collection explores the paradox one can feel between one’s upbringing and what one becomes afterward. More specifically, it’s about feeling excluded from contemporary imagery. It comes from my lack of images, clear illustrations, and a unified representative heritage when it comes to my origins. Sephardic Jewish tradition doesn’t represent itself. It adorns and protects, it hides from the view of others and the « eye ». My title, Everything sinks but the kitchen, like the famous idiom, reflects a haste to leave. Noticing the overflow, questioning what we accidentally filter up, out of habit or intuition. The sink is me, and my flight instincts.

How did your materials and techniques translate those ideas?

This collection is made out of a mix of my textile techniques: naturally dyed prints, scales of wood on fabric and an obsession for knitwear, including weaved-in guitar strings and different kinds of linen. My aesthetic comes from a very specific and personal visual language that I invented through books of collages and drawings of characters – part of a profane mythology and a deeply inauthentic religious lifestyle. Some of it is tainted with my obsession for metal music and guitar players.

How did HEAD Genève shape the scale of your vision? And what comes next?

My time at HEAD gave me the opportunity to elaborate a collection of thirteen looks, which is a lot more than what most schools ask for. It allowed me to envision something on a much larger scale than what I was used to. It pushed me to reach out for help and collaborations. What I remember most about the show is my seven classmates and I, holding each other and being emotional as our collections went out. I would love to continue working like that and present a project for the Hyères Festival.

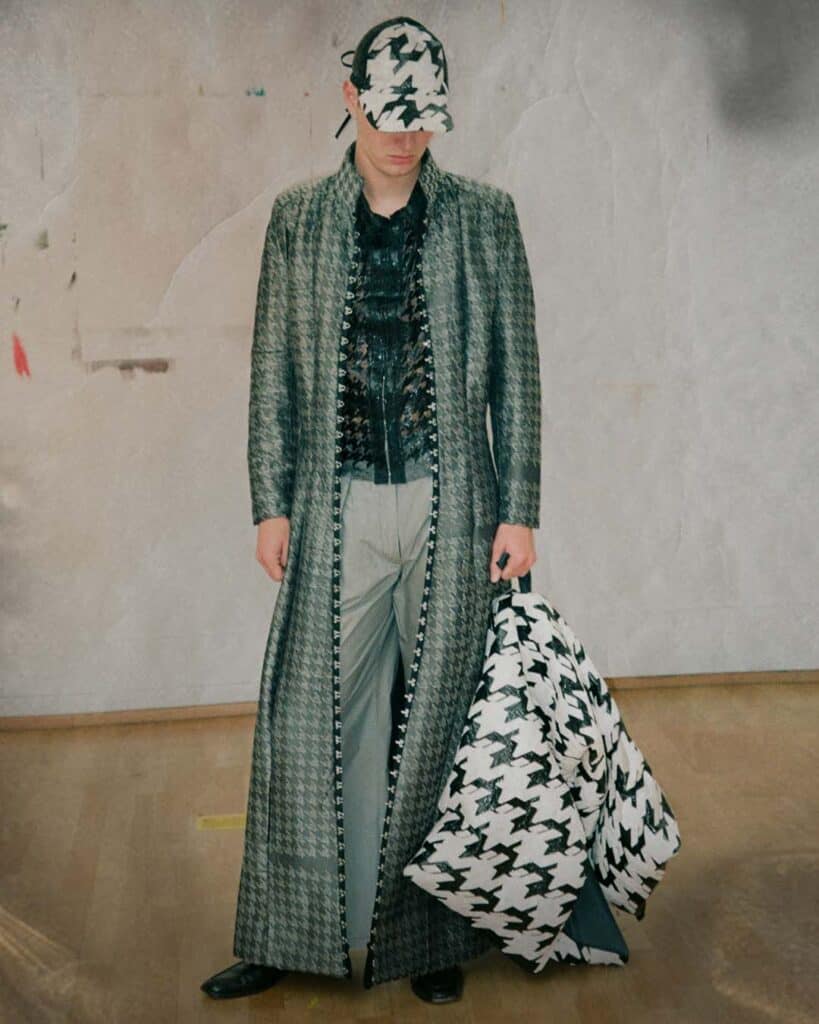

Ewen Danzeisen, Meet The Crows (MA) – Winner of La Redoute × HEAD Prize

What inspired your silhouettes, and how do they relate to how you want to feel in clothing?

The goal for my collection was to conceive garments as lived experiences, not just images – that’s when they fully become real and meaningful. My starting point was my own relationship to garments. What do I like, but also how do I want my garment to make me feel? Big and ample silhouettes, lots of layering, big comfy puffers, a touch of tailoring, and my Japanese roots – all of that is what I need to feel contained, safe, confident, and I guess a little intimidating. In Japan, where my mom is from, taking too much space in public and generally being loud is frowned upon. I wanted my silhouettes – my crows – to slightly reverse that posture: impressive volumes that make one’s own space, but also this shyness and reserved attitude which defines me.

Could you talk about working mostly in black and how you developed your materials?

The use of mostly black color was both a nod to my own way of dressing and a way to invite people to come closer to see what’s happening – I love black because it isn’t loud, but also has this presence. Yes, black sells well, but in a large collection with layered silhouettes, I needed to be really careful. My collaboration with Gruppocinque allowed me to really play and finetune the hues of black in my collection. Lots and lots of black, but also mixes of textures through nylons, wool, leather, heavy cottons, etc.

What do you want people to understand about your crows and how they’re worn?

I take the most pleasure out of making big outerwear garments – bombers, puffers, long coats – so that’s where I started. Mixing both my inspirations and skills came as obvious. I wanted to balance bigger pieces with the layering and simpler pieces they deserved. Sling bags, caps (my crow beak caps), scarves. It’s not just the big pieces, but also the accessories and the small details that make you want to look closer, touch and wear my collection. And finally, the crow: usually perceived as a bad omen, but really just a shy, smart and playful guy. I really want people to meet the crows.

Majd Eddin Zarzour, The Distance 0 (MA)

What is “the distance 0,” and what ideas shaped this collection?

My collection the distance 0 is the manifesto of our brand Majik Noir. The collection explores the topic of asymmetrical warfare. It is inspired by radicalized minorities that use fashion to combat social injustice, mainly the queers, the anarchists and the pro-palestinian. Their fashion approach inspired the collection in many ways such as questioning of gender code, embracing imperfection and use of symbolism. Diving in this approach of fashion allowed me to explore tools and materials beyond their usual use and develop complex patterns, sophisticated cuts and advanced patchwork.

How do your materials and construction reflect that political stance?

Our brand is a slow fashion local Swiss brand (including the production) that aims to offer stylish clothes and accessories with sophisticated cuts and advanced patchwork and other textile development. Our aim is to offer cross-matching pieces endlessly stylable with each other and safe spaces to explore one’s visual identity and learn clothes altering skills. Indeed, our brand will propose new pieces, but also upcycling and workshops. In an anti fashion spirit.

What comes next for Majik Noir?

Our aim is to offer stylish clothes and accessories with sophisticated cuts and advanced patchwork and other textile development… and safe spaces to explore one’s visual identity and learn clothes altering skills. New pieces, but also upcycling and workshops.

Thongchai Lerspiphopporn, When Hope Is Not Enough (MA)

How did you arrive at the idea of transforming jewellery principles into garments?

When Hope Is Not Enough” redefines my fashion practice by translating the structural logic of jewelry into garment-making. The collection began with the realization that my long-held craft skills were no longer sufficient in their original form; they needed to evolve. Instead of using jewelry as adornment, I treat its mechanics–linking, securing, interlocking–as the foundation for seams, volumes, and silhouettes. Each look is built through hand-assembled components, modular systems, and material experiments, many of which involved countless failed trials before finding the right balance of flexibility and strength. Working without a traditional background in pattern cutting or machine-based construction, the collection relies heavily on hand-craft, precision, and an architectural approach to making. The result is a body of work where craftsmanship becomes structure, and jewelry becomes a method for fashion.

What did the learning process at HEAD Geneva open up for you creatively?

Studying at HEAD Geneva was a process of rebuilding from zero, transforming my perspective as a jeweler into that of a fashion designer. Although the school offered guidance, resources, and technical support, the journey was driven by self-learning: adapting to new materials, production methods, and ways of thinking. This mix of independence and support shaped my voice as a designer.

And what direction do you hope your work takes next?

Moving forward, I aim to continue expanding this hybrid language of craft and fashion, exploring new techniques and deeper material research. I hope to bring this approach into a professional context, collaborating with fashion houses that value craftsmanship and innovation, and contributing a perspective rooted in precision, construction, and individuality.

Norma Morel, Madeleine (MA)

What ideas guided the creation of your collection Madeleine?

With this collection, I wanted to create a dialogue between past and present: an ancient wardrobe and my own world. One of my deepest inspirations comes from the memory of my grandmother’s atelier and the relationship we built together – she is the one who pushed me into fashion. I chose to mix pieces inspired by the old men’s wardrobe, partly from the 17th century, such as structured blouses and long coats, with more delicate, intimate elements borrowed from women’s lingerie. This contrast allows me to play with notions of strength and fragility, intimacy and appearance, and to question the boundaries between genders. Lace and silk are integral to my research for their finesse, transparency and sensitivity. They stand in stark contrast to more rigid or technical materials from the streetwear world, such as fleece and nylon. I like the idea that delicate fabrics can be worn in a strong, assertive way.

How do your fabric choices connect with memory and heritage?

I’ve chosen fabric treatments that evoke the wear and tear of time, as if the garments had survived the centuries. Tartan, in direct reference to the tartan found in my grandmother’s house, is a common thread running through the collection. I use it as an anchor motif, almost like a signature, but reworked in more contemporary cuts. My collection is a dialogue between past and present, a mix of codes, a game between delicacy and structure. It reflects who I am today: a mix of memories and contrasts.

What comes next for you now that your Master’s is complete?

Now that I have completed my Master’s in Fashion Design, I am ready to turn the next page and begin shaping my own universe. My ambition is to develop my brand and open a boutique in Geneva: a space where my creations can live, breathe, and evolve. I imagine it as a meeting point between emerging voices and established talents, where my pieces are shown alongside the work of other designers I admire. This boutique will also host a carefully curated selection of second-hand treasures, giving existing garments a new life and offering a more thoughtful, circular approach to fashion. In this hybrid space, I want to celebrate craft, creativity, and sustainability, while building a community around a shared love for meaningful design.

Léon Narbel, Noms, Prénoms (BA) – Winner of Bachelor Bongénie Prize

Jewellery made in collaboration with @aliciamaderland

What sparked this collection and the idea of anonymity?

This collection is called Noms.prénoms.ch. It is part of an ongoing anonymous project I have. We work – I say “we” because I am always collaborating with others, and because the focus should be on the garments and accessories rather than on a single designer or face. Nom.Prénom.ch is a creative project, not a brand, born out of a desire to slow down and create meaning. It imagines clothes as intimate objects that carry memories and create lasting bonds with their wearers. Inspired by the idea that “ideas think us,” we question temporality, transmission and authenticity in clothing design.

Could you tell me about your approach to construction and why it matters?

The research focuses on one-piece pattern making because it reflects our philosophy: unity and constructive simplicity. We work with what we call systems: ways of building garments or accessories that can be applied across archetypes. The first comes from folding a cross in two and cutting a hole into it. The second comes from peeling an orange in one piece, a need to slow down and take time to understand simple things. The third from an old US Air Mail bag:folds that create volume without shoulder seams. Modularity is important too: pleats that change with your body, tank tops that drape differently depending on your mood, bags with multiple handles or snap buttons to evolve over time. We want people to interact with their clothes and understand how they’re made.

How did studying at HEAD shape your approach, and what comes next?

Studying at HEAD was as challenging as it was interesting: very supportive technically and mentally, always pushing further when needed. Now I want to start a Master’s in sustainable development so I can teach design and sustainability, and also do consulting. I want to preserve my creativity as a pleasure and keep experimenting with patterns, designs, objects and materials. I’ll continue making clothes as long as I live, for people who truly want them, or simply for myself, friends and my lover.

Asma Haddad, Beyna Benkine (BA) – Winner of Prix Image / Direction artistique remis par Le Bal des Créateurs & Kevin Murphy

How did your story shape Beyna Benkine?

My name is Asma and it will be 4 years since I left my country, Tunisia, and my family to come study in Europe. After 1 year in Paris in a preparatory art class, it was at HEAD Geneva that I decided to continue my course to make my passion my future. It is at HEAD that my artistic sensitivity has developed, my technique has been forged and that I have emancipated myself intellectually. I was starting from zero but thanks to my teachers who are aware of everyone’s creativity and my class which has become a family, I have built myself and I have blossomed.

How do you merge Tunisian heritage with streetwear?

Through this collection, I chose to tell my story by combining two vestiaires that are familiar to me: Tunisian craftsmanship and streetwear. I grew up in the first and I am evolving today in the second. Beyna Benkine extracts the traditional clothing to integrate it into an urban wardrobe, translated through a non-Western and identity prism. Between memory and modernity, Beyna Benkine rethinks streetwear and brings back to life a craft of yesteryear rocked by memories, passion and nostalgia.

What identity does Beyna Benkine express?

The bias consists in merging these two universes without prioritizing one at the expense of the other. It is neither to orient sportswear nor to folklorise traditional clothing, but to create a hybrid territory that reflects a fluid, moving and multiple Tunisian identity. This collection explores what it means to wear a heritage while moving forward. It is a collection that pays tribute to the textile and symbolic wealth of Tunisia while offering new forms, freer, more current, closer to everyday life. Through her, clothing becomes a territory of expression, pride, and reinvention.

Mélanie Schiewe, Pretty In Pink (BA) – Winner of Prix de la Commune de Collonge-Bellerive – Soutien à la production

What inspired Pretty In Pink and your approach to gender?

This collection is inspired by a very personal experience linked to the way I’ve related to clothing since childhood. When I was little, my mother dressed me in what’s considered “feminine” clothing: dresses, pink, skirts, ruffles. I loved it, but it wasn’t always practical or comfortable. Later I became interested in the “masculine” wardrobe: simpler and easier to move in. As I grew older, I realised how much the way I dressed changed how people perceived me. When I wore feminine clothes, I was taken less seriously and felt less safe. When I wore masculine clothes, I suddenly received no respect. I grew tired of choosing between extremes. My collection hybrids these universes to create a wardrobe that feels true to me: comfortable and empowered. Ribbons, bows, ruffles represent resilience through softness: fragile at first glance, but actually strong. Football is a key inspiration, its symbols mixed with delicate elements. It’s about deconstructing stereotypes with humour, lightness and freedom. You can be strong without rejecting softness, soft without losing strength.

How did studying at HEAD shape your confidence and creative freedom?

Studying at HEAD has been a great opportunity. My class was incredibly supportive. Being able to share ideas and doubts helped me move forward. At HEAD, each of us has the freedom to explore our own universe. There isn’t really a “wrong direction.” Of course, you still have to defend your project, but HEAD gives space to experimentation, and that allowed me to find my voice.

What are your next steps?

For the moment I’m working in a clothing store to gain money and experience. Next, I’m looking for an internship in Paris or London, to gain a clearer understanding of the fashion industry. I feel I need to step out of the school bubble. And maybe afterwards, I’ll consider pursuing a Master’s in textile experimentation.