Jake VanDorn (George C. Scott), a devoutly Calvinist business owner from the Midwest, lives a life centred on work, family and God – until his teenage daughter Kristen (Ilah Davis) disappears from a church trip, turning up months later on an amateur sex tape. Unsatisfied with the efforts of the police, Jake sets out into California’s seedy underbelly to find her himself.

It’s screening tonight (30th July) at The Nickel, a 37-seater grindhouse cinema that boasts a curated programme of the transgressive, the forgotten and the downright bizarre. A passion project of proprietor Dominic Hicks, the cinema is a reaction to what he sees as the increasingly sanitised ways that art is produced and consumed. “I look for things that are not so cautiously created. The flaws in it tend to be where the interesting moments come through,” Dominic explains. We’re catching up in the basement, now a fully-licensed bar and extension of this vision – think scuzzy paint-stained floors, deep red walls and exposed brickwork papered with retro softcore mags. “I miss when artists were putting themselves out there and they were wrong. Their wrong-headed feelings, their prejudices, their flaws. Where they fall short of the mark and it’s just there on the page.”

Legs McNeil, punk legend and co-author of The Other Hollywood: The Uncensored Oral History of the Porn Film Industry, feels similarly. “It just seemed a bit of nonsense to me,” he explains in a pre-screening video interview. “They didn’t have to kidnap anybody. Everyone in the porn industry wanted to be in the porn industry.” He also disagrees with the dichotomy the film sets up between sex work and faith. “Some of the most Christian people I ever met were porn stars. There were a lot of very decent people and a lot of very indecent people. Like life.”

But Jake VanDorn’s real-world counterparts weren’t too pleased with the movie either. Schrader chose to set and film the first act of the movie in his hometown, Grand Rapids, Michigan, but was not received with a warm welcome by the townspeople. In a 1979 interview with the LA Times he revealed that the town also did not like the movie, considering its depiction of Dutch Reformation Protestants a caricature. And like Kristen, Schrader too is a California runaway, diverting to study film at UCLA instead of training for the ministry. He was even fired from his hometown job for writing a film article in a student newspaper because his devout community frowned upon the entertainment industry as a whole.

When I point this out to Dominic, he’s surprised – and pleased. “So he’s a natural contrarian!” he grins. “And now he’s conservative because Hollywood’s gone left. That’s what he’s interested in – being a stick in everybody’s side.”

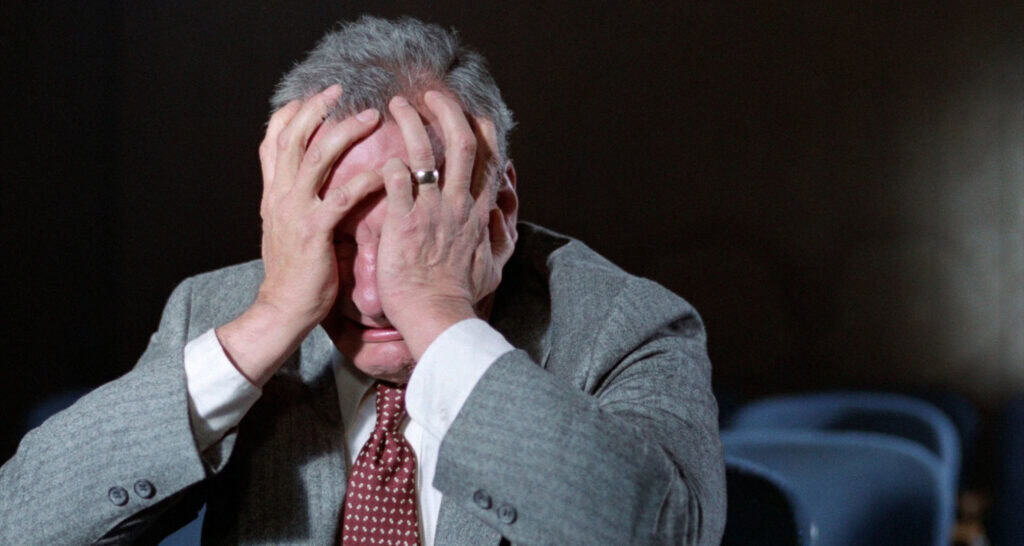

This to me is the crux of Hardcore. Conservative in its resolution, Protestant in its thrust, but slippery in its delivery because it enacts the very thing it condemns. The AAFA didn’t like Hardcore because of its stance on porn. Perhaps the Calvinists didn’t like Hardcore because, like the jailbait, virgin-defiling genres of its namesake, it paints a portrait of a God-fearing man and subjects him to ritual humiliation. Our pleasure as viewers lies wholly in Scott’s performance of intense mortification throughout his time in the underworld – we revel in seeing where he must go, what he must wear, what he must witness. It’s not his teenage daughter that the camera lingers on as VanDorn watches her sex tape: it’s Scott’s tortured face, a drawn out sequence of tears, screams and rendings. In Hardcore, we are watching a kind of spiritual pornography, the fantasy of moral agony. And we delight in it.

In some ways, it’s the ambivalence of the film that situates it so perfectly in The Nickel’s programme. Immaculate from a technical perspective but muddied in its morality, it’s these kinds of imperfections that Dominic looks out for – hypocritical, perverse, ugly. “And you can walk away afterwards and you don’t have to have dinner with the c***t,” he adds. Instead, I leave The Nickel feeling elated that this kind of aesthetic sensibility isn’t dead.