Every now and then, a video resurfaces of Slam Bamboo, a forgotten ‘80s electropop band, playing a segment for live television for the Cleveland, Ohio area.

As the chipper TV host presents them to the eager applause of Middle America, the camera swoops round to the singer, a young man with glasses and hair in the shape of a curly rhombus, who launches into their apparently hit latest single. It’s so nice, waking up to you, he warbles, as an even curlier haired drummer bounces around in the background. The song is sugary sweet, perfect for the audience of spectacled older women in stiff tweed blazers that watch from the stands. Then, at some point, the camera flicks away once more, this time to the keyboardist – and we finally catch sight of him. An inexplicably young Trent Reznor, a far cry from the grimy frontman of the band Nine Inch Nails that he is fated to become. And yet, however domesticated for the masses of live broadcast, his all-black outfit singles him out from the rest of the band like a thumb so sore that it’s suffered third-degree burns. In this flickering spectre, a prophet from a long-forgotten past, the ghost of a machine starts to shake its chains.

Nine Inch Nails solidified their reign as the darling of 1990s alternative rock through a combination of catchy song structures, raw lyrics, and a bacchanalian blend of industrial, new wave pop, and metal genres. The result was something much less a plastic industry product, fit with all the glistening bells and whistles of a Mattel doll, than a Lynchian cyborg of disturbing proportions. Though their 1989 debut, Pretty Hate Machine, put them on the map with its synth-heavy screams and monstrous thumps of percussion, it was with the 1994 release of their second LP, The Downwards Spiral, that put them on the map.

The album was recorded at ‘Le Pig’, Reznor’s L.A. studio – also known as 10050 Cielo Drive, where Sharon Tate was murdered by the Charles Manson crew. It’s here that many of their best-known hits were released into the wild: opening with the tumultuous ‘Mr Self-Destruct’, the track list goes on to include ‘Hurt’ (famously covered by Johnny Cash), as well as ‘Closer’, whose music video sent unsuspecting MTV viewers across the world foaming at the mouth.

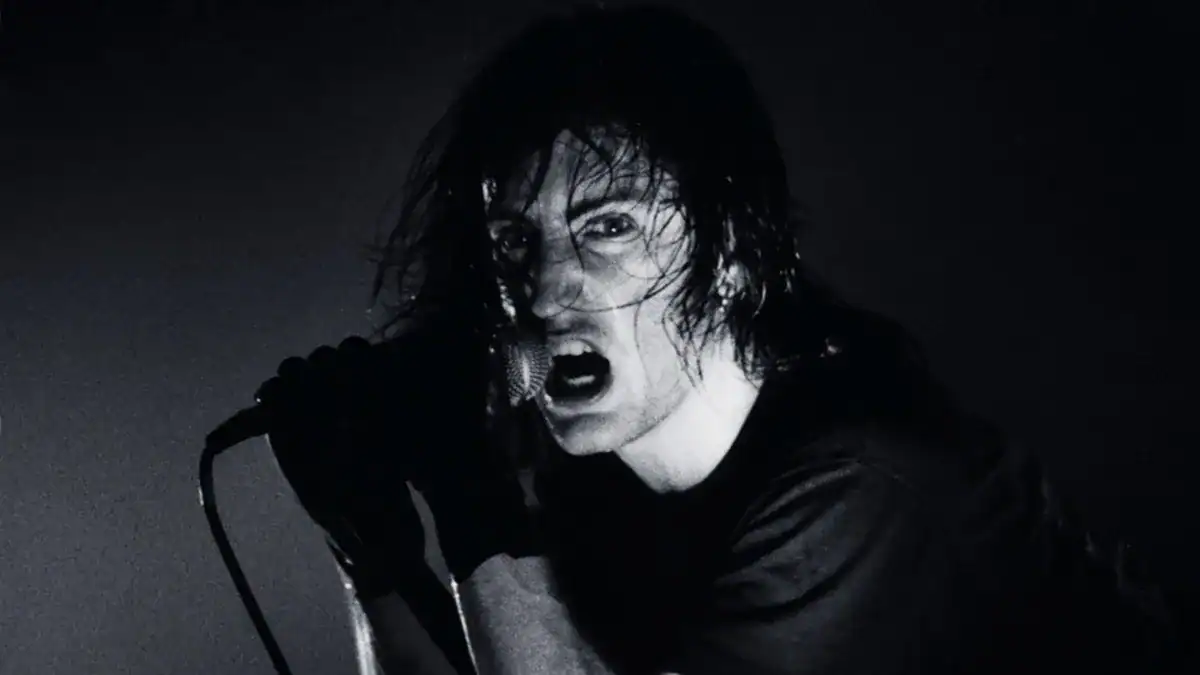

Director Mark Romanek’s visuals are both stomach-curdling and violently moreish. In one shot, Reznor, blindfolded and bound, gasps in pleasure before the camera; in another, he screams in full close-up, cheeks bristling as his furnace goggles brace against an unseen force. All mesh and leather, he churns and stares between segments of various oddities: a monkey tied to a crucifix; an infantile skeleton; a beating human heart, plugged into a web of plastic tubes. Beating back and forth throughout, Reznor belts the radio-friendly litany of the record (I want to fuck you like an animal / I want to feel you from the inside) with two sliced-up cow carcasses swinging from hooks behind him. It’s the feeling that you’ve intruded on a mad scientist’s laboratory – and, upon swivelling to grapple for an exit, found that the way out is far, far behind you.

Yet despite the music video’s grotesqueness (not to mention the incessant bleeping required of a radio-friendly edit of the song), ‘Closer’ rocked MTV like a grenade in a Barbie store. The channel’s viewership had skyrocketed into the new decade with a new generation of rockstars, popstars, and 24-hour cable programming, until its name became synonymous with the loved and loathed world of the mainstream music industry. Nine Inch Nails finally became a household name, pioneering a new wave of industrial metal that would prop up artists like Marilyn Manson and Rammstein in its wake. However, this was not without its controversy. The foundations of what became known as ‘industrial’ music had been laid with bands like Throbbing Gristle and Monte Cazazza, grubby misfits who had crawled their way up from the underground with their sounds of thrashing machinery and grating vocals, all primed for maximum indigestibility. As ‘Closer’ went painfully mainstream, Reznor’s twisted vision may have scared respectable Middle America to death – but boy, did it sell.

But it’s wrong to frame Reznor’s artistry as yet another tale of corporate ‘selling out’. The paradox of 1990s popular culture fetishised often-abstract concepts like ‘independence’ and ‘authenticity’ against the backdrop of a hungering neoliberal economy – one fraught with the onslaught of an advertising frenzy upon everyday life with a never-before-seen ferocity – only for what was once ‘alternative’ to be sucked into the gaping maw of its capitalisation. Nirvana had suffered it only a few years prior, despite their vehemently anti-industry posturing – soon enough, the whole ‘grunge’ scene (the label itself pushed upon the ‘Seattle sound’ by the media, fusing Kurt Cobain’s basement punk with Soundgarden’s psychedelic metal riffs as if they were the same beast) had fallen victim to the pariah status of ‘sell-out’.

When they played Woodstock Festival 1994, thousands of restless concertgoers jostled and heckled in the crowd, ready to blow. They were one of the biggest attractions at an event boasting the likes of Aerosmith, Bob Dylan and Santana – and yet, when the performance shuddered into gear, it wasn’t radio-friendly melodies spurting out from the speakers, but grinding, gurgling, machinelike noise. Reznor and co exploded onstage covered in mud, a wry reference to the antics of the crowd that had been left to fester in the pit. As they burst into a rendition of ‘Terrible Lie’, they move like the cogs of a lurching, mechanical monstrosity. It’s a hazy, raging fever dream, a nightmare of wailing and muscular spasms, as if each member of the band were trapped in a testosterone

Much of the staple ‘90s look that permeated everything from Buffy to Blade sprung from the tsunami-like presence of Reznor and his disciples. Leather was king, from trench coats to trousers, exerting a bullish look of hypermasculinity – slick, angry, dominating. As he shoves and staggers back and forth in his performances, crashing into the unsuspecting shoulder of a guitarist, the unprotected limb of the drummer, the innocent appendage of a sound tech rushing to replace the mic, Reznor collides around the stage like a wartime berserker. The keyboard, once the instrument that kept him domesticated on daytime television, is pounded, assaulted, dismembered – in one recording, Reznor subjects a Yamaha DX-7 to a perverse sexual scenography, to the roaring approval of the crowd. The Self Destruct tour was a feeding frenzy for the freaks, ultra-violent and hyper-testosteronized, grinding across continents to sink its rust-stained teeth into whichever sadomasochist would reach out and let it.

At the same time, this hyper-macho fever dream was subversively feminine, aching with the allure of S&M culture and, crucially, the perverse vulnerability that crept out from each performance. Reznor would often appear onstage in makeup, more alike to a cabaret performer than the devil-worshipping nut many media outlets gleefully made him out as. His face is ghoulish – yet almost delicate, verging into drag as the macho pretensions of his contemporaries fall flat and boring in comparison. As he screams about bloodstains, Hell, and the death of God, Reznor rocks garters and fishnet stockings, flagrantly rejecting the posturing of the glam rock and hair metal that had dominated the 1980s.

What’s left is something tender – yet theatrical, too. Pointedly unlike Cobain and his signature lumberjack flannel, Reznor delighted in the darkly flamboyant, taking the dramaticisms of heavy metal with the flair of subversive drag elements. As the guitars descend into mechanical crackling (using the signal-processing software Turbo Synth, his riffs descend into pure noise, rising and rolling with a nightmarish thrill), a fleshy hitch of breath catches in the air, hiding behind the crush of the machine.

Reznor is an anomaly, a rich complication in a sea of the straightforward. His music bleeds out like inhuman sonic ooze from an industrial corpse, slamming and revving up a flailing mass of aluminium parts. It’s pure power: the grinding of bodies, the cyclical distress of a band in total, hive mind synchronisation. At the same time, he casts his spell across his audience with an unexpected rawness, peeling back the skin to reveal the nerve endings beneath. He’s macho yet delicate, a sell-out yet subversive, a mechanical crush of contradictions. Reznor is, after all, human under that machine. Not a robot or an automaton, but a cyborg – flesh and blood and steel.