We fear change. We fear ageing. And, most of all, we fear what it means to vanish – to be here, then not. As Epicurus once wrote, death is not a thing to be feared because it is nothing at all: while we are here, she is not, and when she comes, we are gone. Still, we resist it; we chase permanence, treat it as virtue, and build entire industries to mask the inevitability of time. But releasing that resistance opens something else, a space to witness what’s already passing. What does it mean to carry the feeling of something that’s already gone? In our boundless quest for continuity, Milena Naef’s sculptures suggest something more transient: a body passing through space, leaving only a trace of its form. There is no promise of restoration, only a quiet moment to hold space for what, inevitably, slips away.

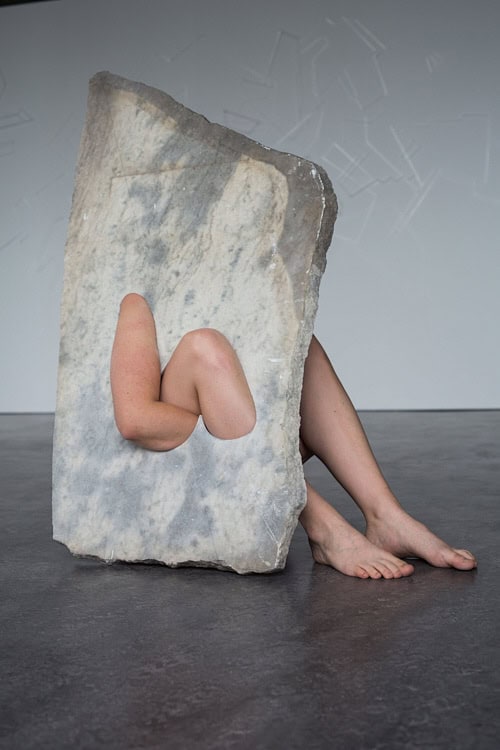

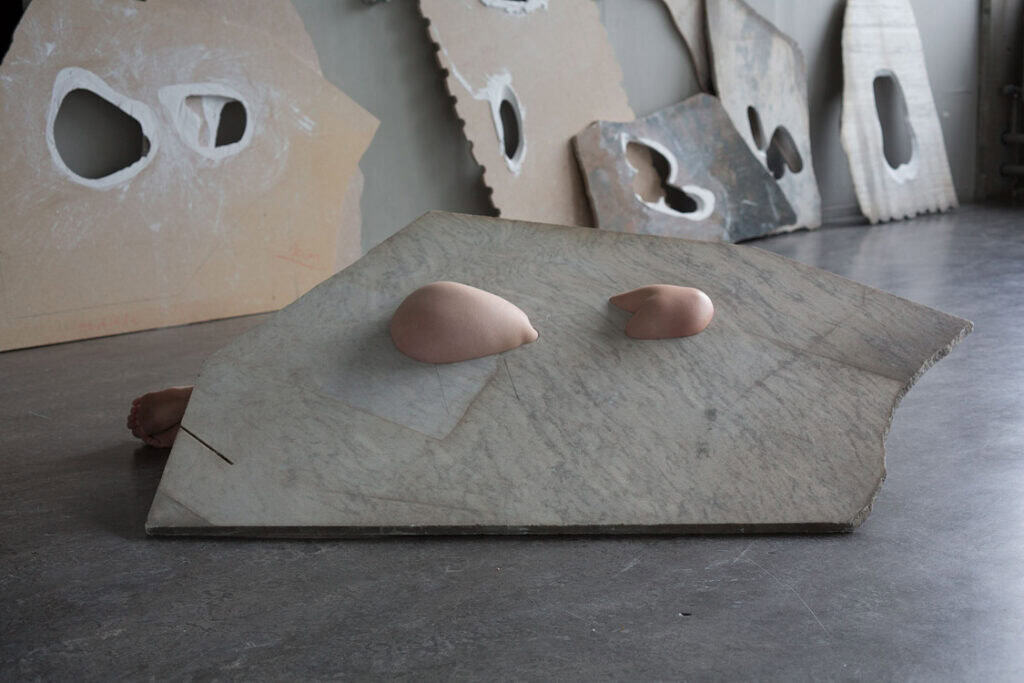

In her ongoing series Fleeting Parts, the Freiburg-based artist carves negative spaces from slabs of marble, voids designed precisely to accommodate her own body. These openings are not figurative carvings but exact bodily impressions: hips, legs, shoulders, back. The marble, cool and seemingly immutable, becomes a resting place for something as shifting and impermanent as flesh.

So, how do you carve for the body without ever depicting it, making space for something rather than from it? Naef didn’t set out with a fully formed concept. Her practice emerged in response to a sculptural lineage (and an instinct to deviate from it). As the fourth generation in a family of stone carvers, she speaks of feeling pretentious when attempting to work in traditional ways. “Coming from a family of sculptors, where the method involves removing material to shape something figurative, I felt that working in that same way wouldn’t make sense for me,” she explains. Without formal training in classical stonework, she instead found herself developing a language of absence; where her predecessors carved mass, she began carving space.

One of her first explorations was Weight of Four Generations, in which she carved the negative space of her leg into a marble block and rested the sculpture on her own body. The work’s instability, its reliance on the presence of the body, and its reluctance to settle into a final form would become defining features of her practice. “Is it complete when the body is inside? Or when it’s separate?” she asks. “That kind of ambiguity really excites me.”

The marble in Fleeting Parts carries the same sense of provisionality. “The work includes that potential, that memory or trace,” Naef says. “These slabs will outlive me. They become a kind of archive of the moment when they fit me. In ten months, maybe they won’t fit anymore. In sixty years, I’ll be gone.”

Though often associated with timelessness, marble is, in her hands, unpredictable and fragile. She frequently works with leftover slabs: damaged, weathered, already broken. Many bear a patina from years of rain. “I like to take these pieces as they are,” she says, shaping them only where necessary to accommodate a curve of her body. The choices are intuitive rather than symbolic, guided by the material’s limits and her own. Framing the Body pushes this fragility to an extreme: a three-dimensional structure built entirely from thin marble frames, seemingly held together by nothing but their own tension. “There’s a sense of volume, but it’s also just lines – very minimal, very delicate,” she says. “Nothing is really holding it up except itself.” It’s a piece that lays bare her interest in the instability of materials we think of as solid.

When she steps into a sculpture, the moment is brief and unannounced. Naef avoids calling these actions performances. “It’s just an interaction,” she explains. “I don’t stay in there for long. It’s not about spectacle; it’s about making that connection between the body and the material, even for a moment.” Often, her face is hidden in photographs, a decision that allows her body to become more universal, more sculptural. “I like the abstraction of seeing a body part–maybe you don’t even know which one–emerging from this heavy material,” she says. “There’s this strange contrast between softness and weight, between body and stone. And in that moment, I see the body not as a subject but as a material in itself.”

This logic of fragility runs through her work with glass as well. She discovered the material unexpectedly, arriving at the glass department of the Rietveld Academy after stints in film, sound, and jewellery. Working with kilns instead of the hot shop, she developed a technique of layering her drawings beneath sheets of glass, which fracture unpredictably in the firing process. “I can’t control how they break,” she says. “That aspect of letting go, of not being fully in control, is something I’ve come to appreciate.” There is clarity and wisdom in this surrender—Siddartha’s river running through it, teaching that all things flow. To grasp too tightly is to agonise, to release is to see: a philosophy of impermanence exquisitely embedded in Naef’s practice.

Despite the minimalism of her materials, her practice is dense with complexity. “For me, there’s already so much going on in that simplicity,” she reflects. Glass and marble, while compositionally and historically distinct, share a common tension in her hands. Both carry geological memory, formed under pressure, once fluid, now still. “The marble I use has these beautiful veins,” she says. “You can see the movement in the stone. It captures a moment of it being fluid, like a memory.”

Asked where she might one day like her work to appear, she imagines placing her sculptures in foyers and interior thresholds; transitional spaces designed to house bodies, to shape how we move and gather. These built environments mirror her sculptural language: voids shaped not to resemble the body, but to acknowledge its passing. Her attention to embodiment is both poetic and political. “We all take up space just by existing in a body,” she says. “That presence, that trace, is something we can try to be more aware of – how we move through and interact with our surroundings.” In her work, spatial awareness becomes a form of agency. “The way we occupy space says a lot about identity, access, and presence,” she adds. “My work reflects on that, on how the body leaves marks, both visible and invisible.”

Her sensitivity to the body has recently taken on a more collective form. She is a founding member of MARS (Maternal Artistic Research Studio), a growing network of artist-mothers working across Europe. “It’s about asserting the right to be both an artist and a mother – not one or the other,” she says. “We needed a space to talk about that honestly.” For an artist so attuned to the structures that hold us, this collective is a natural extension: a new kind of architecture, shaped by care.

What lingered after speaking with Naef was the way she returns to the act of observing; how a curve of the body can shape stone, what kind of space we enter, pass through, or leave behind. There’s no need to over-intellectualise it – she’s not making grand declarations. But there is a kind of thoughtful discipline in how she works: trusting instinct, leaving room for change, accepting that not everything needs to be controlled or completed. It’s not a rejection of permanence, exactly, but an honest reckoning with the fact that we never really had it.

One thing is clear. Whether marking herself in marble, translating drawings through shattered glass, or building structures of care, Milena Naef’s work returns again and again to a single, insistent question: how do we inhabit space, and what remains after we leave?

Naef’s work is currently on view at the Clark Art Institute in Massachusetts as part of Ground/work 2025, an outdoor exhibition exploring global craft traditions through contemporary sculpture. Her contribution, an abstracted marble form nestled into the landscape, extends her ongoing dialogue between body, material, and environment.