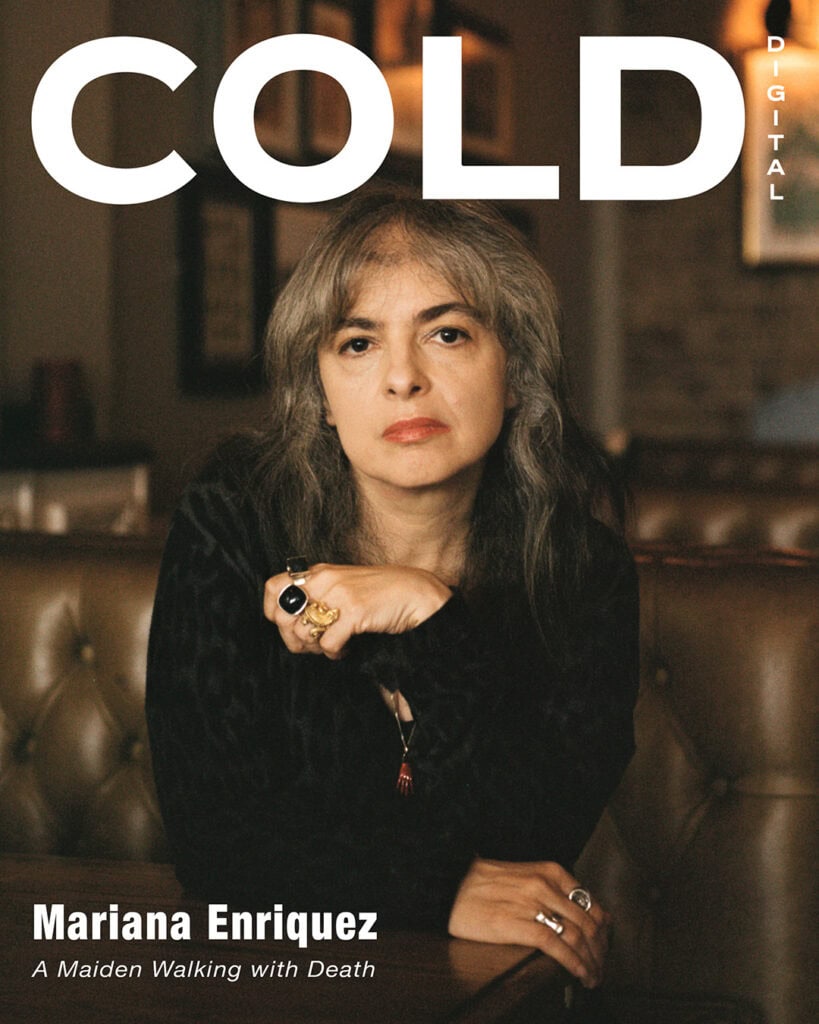

Here lies nothing. Just dust and bones. Nothing. So states a tomb in Recoleta Cemetery, belonging to a certain Mendoza Paz and, one day, to the ashes of Mariana Enriquez, if her friends are to fulfill her wishes. For Enriquez – celebrated Argentine author, powerhouse of the neo-gothic genre, rockstar of all things morbid and occult – death is everywhere. In her beloved short story collections, it takes the form of ghosts, children, insatiable fetishes. In her latest novel, Somebody is Walking on your Grave, death is a little different.

Originally published in Spanish in 2014, Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave has since been revised and newly released in a luminous English translation by Megan McDowell. It marks Enriquez’s first work of translated non-fiction, a memoir chronicling her pilgrimages to cemeteries around the world. In the opening story, she recalls a youthful trip to Genoa, where she met a street violinist who accompanied her through the Staglieno Cemetery, a marble celebration of Eros and Thanatos (the ancient Greek personifications of Love and Death, respectively). There, amid the statues, they made love and parted ways, never to meet again. It was at this moment, she tells us, that her love affair with cemeteries began, a fascination that would carry her across continents, in the company of friends, guides, lovers, or, occasionally, alone.

This book does many things at once. In each chapter, Enriquez visits a different cemetery, becoming part anthropologist as she uncovers the histories and traumas buried within. Each chapter also stands as a contained story of her own travels, a portrait of lesser-known corners of the world animated by their Gothic sensibilities. But perhaps most compellingly, it offers longtime readers a glimpse of Enriquez herself – funny, passionate, and sharp, a friend accompanying you through the dark.

The Cold Magazine (CM): I loved the first chapter. It’s such a fun, evocative piece about young love, your fascination with cemeteries in Genoa, and that erotic experience among the tombs. I was wondering if what you describe there, especially that moment of desire in the cemetery, marked you beyond being just an introductory story. Did it shape you personally or influence your writing in a deeper way?

Mariana Enriquez (ME): I don’t think so, at least not directly. It’s more of an accumulation of things. I chose that story to open the collection because I wanted something young, fun, and nostalgic to show that early fascination with the gothic and the romantic. But cemeteries also have that sense of trespassing, of entering a space that’s forbidden or mysterious. I never really thought of it that way when I was younger, but I see it now.

And of course, I’m Argentinian; I grew up during the dictatorship, when people were being disappeared. There’s another piece in the book where I write about attending the funeral of a friend’s mother, a delayed funeral, because she had disappeared in the 1970s, and her remains were only found in the 2000s. So that gave me the idea that beyond my young fascination, and the fact that as a writer I’m fascinated by ghost stories and urban legends, there was also this deep, political, traumatic, personal feeling.

CM: A thread that runs through these stories is your interest in Gothic literature and its authors. The opening reminded me of Mary Shelley and the myth that she lost her virginity on her mother’s grave. Do you see yourself as part of this Gothic lineage, and do these authors become reflected in your own life?

ME: I learned, as I was investigating other writers, especially female ones, that there’s a very strange kind of kinship. At first, when you start writing, people sometimes ask, “Why do you choose horror when most horror writers are men?” But that’s not true. Most of the important horror writers are women.

All three Brontës, all the main ghost story writers of the nineteenth century like Elizabeth Gaskell, even in Spanish literature too – those women were always nearer to the supernatural, to the Gothic, to that intense romantic thing. And I mean “Romantic” as in Romantic literature, not falling in love. You can see that it’s because those feelings and obsessions were not considered legitimate ones, they were seen as things for women to entertain themselves with. In that marginalised space, they built a tradition. So yes, I do feel it’s connected – something you might not notice at first when you start, but later you look back and realise, Oh, and she, and she, and it’s pretty amazing.

CM: I love Gothic literature, and I’m fascinated that it has become so popular again – even though for a long time it was disregarded. But even when it wasn’t written by women, it always had a largely female readership.

ME: Because women are more attuned to these things. I think at this stage, what women do and what women like becomes mainstream. It’s great! I don’t let people put down “girly” things because they’re mainstream or very popular. Let us have our moment. Why can’t we have our moment?

CM: Something I found recurred in these stories is that you’re rarely alone in the cemeteries. Sometimes, like in San Sebastián, you have friends who are kind of Chiron figures – they take you along. And sometimes, like in Lima, you meet people in the cemeteries. How important do you find companionship within this strange space?

ME: Most of the time cemeteries are quite empty. So the people you find are kind of weirdos, and there’s a camaraderie. It really binds you. In San Sebastián, for example, I start with the fact that my friend Begoña brought me dirt from Dracula’s castle. So you have friends who go with you, who share the same tastes and obsessions, and it’s like a rite of passage to do these things together.

Then there are people you meet in the cemeteries, and they can be fascinating. For example, in New Orleans, I met the artist Arthur Smith. He made the most amazing decorations on graves. He was in his 80s, and the city has been trying forever to get him to do an exhibition, but he just doesn’t want to. His work is in the cemeteries.

Or you find absolute weirdos, like the guy in Lima. There’s something about death and cemeteries where familiarity is OK – I had sex there – but there’s a point where it becomes too much. I can’t always point out exactly where that line is; I only know when I see it. But it’s interesting to investigate that, see what’s wrong, what’s fun.

CM: You spoke a little about your friend’s mother’s funeral, but at what point in your life did you know this collection of stories would become a book – almost like a memoir?

ME: Well, it was when Martha’s mother appeared that I said, okay, this could be something. These are not just combinations. I don’t keep a diary, and the closest I have to one is this. So I decided not to make it just a travelogue; since I found that personal connection, I decided this has to be a memoir.

Because my fiction is very crazy, it’s not autobiographical at all. But if this was going to be personal, I wanted it to be very, very personal. I wanted to make myself, the narrator, also a character. It’s not fiction, but the narrator’s voice has to be a character. It can be just me walking around, but it has to have an authoritative voice about these cemeteries, because I really investigate them. So in a way, I say: I’m a historian, an anthropologist, a folklorist, and a goth.

CM: I have a quote from one of the stories that I found very interesting, where you write that “Argentines have a problem with the subject of ghosts […] they don’t see the attraction, can’t grasp the quaint appeal.” In your fiction, Argentina is an incredibly fertile landscape for ghost stories. Even in this book you detail the insane journey Eva Perón’s corpse traversed. I was wondering if you could tell me a bit about that tension. Does it fuel your writing, or does it feel like you’re pushing against something?

ME: I think I’m pushing against it, yes, but it’s something weird, because it’s like people don’t want to recognize it. For example, the first time I came to London, I remember arriving and thinking, wow, they have haunted house tours. We don’t have anything like that, not because we don’t have ghost stories, but because people are scared of them. They get superstitious, and they don’t think it’s fun. You have to be a sociologist to understand why. For example, people don’t talk about the body of Eva Perón. It’s something we’d rather forget.

It’s strange, because on one hand, very extreme things happen in Argentina regarding death, and on the other hand, everyone shies away from the supernatural part of it. I think it has to do with class, too. South American societies have a deep divide between what’s considered rational, civilised, and the beliefs of not just indigenous people, but also European immigrants who brought their stories from their little towns. All of that – pagan beliefs, indigenous beliefs, European ghost stories – gets dismissed because, as a country, we want to be “civilised.” There’s a big thinker in Argentina, Sarmiento, whose political stance was “civilisation or barbarism.” As a country, we chose civilisation – everything else was considered barbarism. I don’t think people are thinking about Sarmiento all the time, but there’s something in the culture that really rejects that, and that ends up being very dismissive, even awful, toward popular things and popular expressions.

CM: Across your fiction you’re very interested in the dead and in hauntings, but not usually in the setting of cemeteries. I was wondering if you could tell me why these two don’t always come together in your stories?

ME: I’ve never felt cemeteries were haunted in any way. I don’t know why, really… I think hauntings are more on the side of the living than the dead. Cemeteries are places people don’t tend to go; most of them are quite abandoned. They are places of memory, but memory doesn’t really act there. In my short stories, I work with ghosts representing memory, trauma, things happening to the living, so they are near the living. That situation of nearness, that kind of closeness to a ghost or a haunting, wouldn’t really happen in a cemetery, because people don’t interact with that place much. So I prefer ghosts in houses, cars, schools – where people are.

CM: I read that one of the first horror novels you read as a child was Stephen King’s Pet Cemetery, a gift from your uncle. I was wondering if that was formative for you, and if it contributed to your love for cemeteries.

ME: Oh, I guess it is. I was terrified, terrified! I threw it away from my body as I was reading. But the pet cemetery – the description of it, the idea – I think at that age I hadn’t even thought about pets being buried. And I was fascinated by that. In the book, the family has it in their backyard. I thought, how cool would it be to have a cemetery in the backyard? There’s a long scene where they read the graves and these birds… I don’t know, I thought it was so cute. So yes, I guess it was immensely, immensely influential.

CM: Another thread I saw across this book was rock ‘n’ roll. There’s both the legacy of dead artists, but there’s also you, as someone who’s very in love with rock and roll. That devotion is something I also recognise in your fiction. I was wondering if you could tell me a bit about this intersection between death, love, and rock-and-roll fanaticism.

ME: I think fandom is one of my big interests, both as a participant and as an observer. I shy away when it gets too crazy, but I still understand the sentiment. In rock and roll, and also in pop music now, especially with women pop stars, there’s clearly a devotion that’s… I don’t think it’s religious; I think it’s mythological. These are our goddesses, and gods, and minor gods, and elves, and we project a lot onto them. I don’t mean that in a bad way; I mean it in a good way. Girls discovered the Beatles, they discovered everybody. There’s something very mystical and mysterious about that.

The connection with death, of course, is obvious – the burning bright and dying young, the 27 Club… It’s a modern myth. And that relationship between artists and fans is very intense. When you fall out of love with a musician, it’s like falling out of love with a real person, you forget completely. There’s a kind of melancholy in that, because something dies inside you. Then, of course, there’s the relationship between women, death, music, ecstasy; that’s mythological too. Women dancing with Dionysus, with Pan, the gods of nature and music – Orpheus being killed by the Maenads because he was devoted to Apollo and not to Dionysus. They loved him too much; they wanted him on their side, and when he wasn’t, they killed him.

I’ve felt that at shows. As a rock journalist, I’ve thought, my God, if they give this man or this girl to the audience, they’re going to eat them alive. That desperation is very religious. It’s like communion: “this is the body of Christ.” There’s a whole ritual, ceremony, devotion.

CM: Finally, as a cemetery connoisseur, do you have a favourite time of year and time of day to visit a cemetery?

ME: Very obviously, before nightfall. Five o’clock is perfect, and in autumn, definitely. In the summer, cemeteries can… this is kind of disgusting, but they can smell. In spring, there are a lot of bees and stuff. In winter, it’s just excruciating, you’re in the middle of nowhere, very open, very cold. Autumn is perfect.