Jafar Panahi walks into Sala Sinopoli in Parco della Musica, a red velvet-clad auditorium in the Flaminio area of Rome. He’s not wearing his signature tinted glasses, so his eyes are visible and his gaze is warm as it sweeps across the applauding room. We are gathered to watch his newest film, It Was Just an Accident, winner of the Palme D’or, make its Italian debut at the the 20th Rome Cinema Festival, held from 15 October until 26 October 2025.

That evening, Panahi was being honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Award by none other than Giuseppe Tornatore, a legend of Italian cinema and the director of films such as Nuovo Cinema Paradiso and Stanno Tutti Bene (Everybody’s Fine). “His films remind us that, above all, cinema is an instrument of peace, a language of freedom,” Tornatore states in his opening remarks, adding that “[Panahi’s] new film has the strength to shake consciences like few others.”

The two embrace and exchange praises. Panahi then calls his wife, Tahereh Saeedi, onto the stage to dedicate the award to her for her birthday, joking in his native Persian, “If I’d known it was this beautiful, I would have kept it myself!” Their daughter, Solmaz, drifts past in a long white dress, smiling knowingly as I wish her mother a happy birthday, also in Persian, when they pass my seat on their way to the front of the room.

Following the receipt of the award and closing remarks, those on stage resume their seats in the auditorium. The lights dim, and I peer over my shoulder one last time to see Panahi a few rows back, looking concentratedly ahead. It isn’t every day that a legend of Iranian cinema, an internationally recognised figure of the country’s defiant art scene, sits in a cinema kilometres from home to watch their latest work with you.

The opening scene transports us to the rural outskirts of Tehran at night, depicting a father driving his heavily pregnant wife and their young daughter along an isolated road. Their daughter, bashful but eager, urges her father to turn up the radio, spurred on by her mother. Though any opportunity for endearment is quickly stripped when the father collides with a stray dog in the middle of the road. The eponymous accident is the perfect example of the butterfly effect – the car breaking down, a squeaking prosthetic leg, a traumatised mechanic, and so on – spurring forward the chaotic tragicomedy which unfolds thereafter.

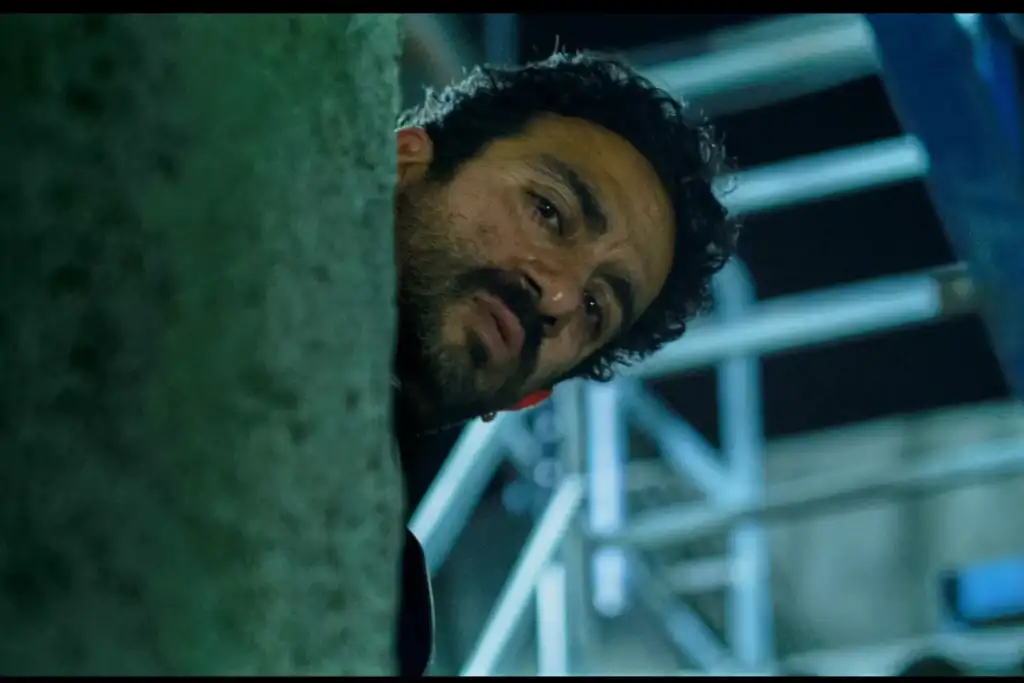

Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri), the aforementioned mechanic, proceeds to rally his fellow ex-prisoners of Iran’s notorious Evin Prison from across Tehran, seeking their assistance in one surprisingly difficult task: identifying their torturous and malevolent prison guard. One by one, bookseller Salar (George Hashemzadeh), wedding photographer Shiva (Mariam Afshari), her bride and groom Goli (Hadis Pakbaten) and Ali (Majid Panahi), and Shiva’s hotheaded ex, Hamid (Mohamad Ali Elyasmehr) partake in this deeply tumultuous and emotionally laborious journey, bringing the worst, and perhaps the best, out of each of them.

It’s not wrong to assume that this film is about revenge, as many have noted. But more significant, I think, are the questions it poses on personal efforts of resistance, recovery, and rectification under state repression. How can ordinary people reconcile the instinct to keep their heads down with the growing urge to demand change? Panahi, undoubtedly drawing upon years of censorship, has masterfully captured the ripples of authoritarianism in this wry and genuine story.

One of the film’s subtler yet most telling depictions of repression lies in its treatment of language. What is lost through subtitles is that Vahid, who speaks Farsi for most of the film, lowers his voice to speak Azeri when on the phone with his mother. Iranian Azerbaijanis, while the country’s largest ethnic minority, maintain a distinct identity from the Persian majority, fostering a sense of both alienation and vulnerability under the state. They often face forced assimilation, with attempts to preserve their language and culture frequently suppressed. In 2016, for example, six Azeri activists were arrested for participating in a gathering on International Mother Language Day on what authorities called “unsubstantiated charges of espionage.”

These sorts of claims on behalf of the Islamic Republic against its people aren’t anything new. And Panahi, having been arrested twice, is privy to this; he seems to use the film to show how oppression permeates all levels of society, affecting men and women, the wealthy and the poor, people of diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds alike. But what he also captures is change. The women in the film are depicted without their headscarves in most contexts, representing a changing tide in Iranian society where women are slowly acquiring more autonomy in the way they publicly present themselves. Similarly, the characters’ unabashedness and willingness to question the very authority that had once silenced them hint at intergenerational shifts in quietly pushing against long-standing restrictions. In this way, Panahi balances a portrayal of systemic oppression with concurrent glimpses of resilience and social transformation, showing that even under intense pressure, the desire for freedom and self-expression in Iran persists.

Back in Rome, during a masterclass the following day, Panahi returns to the stage to provide insights on his filmmaking process. Despite producing a film with such obvious choices for who’s good and who’s bad, villains and heroes, the director’s reflections rejected this notion altogether. He explains that his films are not meant to be political or moralising, but are intended to serve as a window into the nuances of interpersonal and social relationships.

In a film where a former inmate and her prison guard weep together, their shared vulnerability renders them simply human, rather than two opposing political figures. Yet the question of past atrocities remains inescapable. Like Panahi’s characters, we as the audience are compelled to confront a difficult choice: should violence be met with violence, regardless of who’s inflicting it?

As the credits roll after a stark final scene, the audience rises in a rare standing ovation. Panahi stands in his row, illuminated as he acknowledges the room with palpable gratitude. It’s crucial to recognise that It Was Just an Accident is more than fiction; the conflict and hardship it depicts are endured by common people in Iran every day. In the director’s own words from that evening, “when you want to create social films, you are obliged to do all that you can to make it believable – to merge the story with reality.”