“What happened to the warehouses?” sighs one of several girls in colourful wigs when a bustling crowd fails to coalesce for the annual New Year’s Eve street party. By midnight it picks up, but it’s paltry next to previous years and quiet by 6am. Just three years ago I arrived at 6am, confident the bassline would roll over into the next day… and the next.

Harringay Warehouse District, also known as Manor House, is an urban creative village that has flourished in North London for nearly two decades. The concept is as old as the hills: a thousand (predominantly) unpecunious artists and extraverts flock together to live a hippy, communal lifestyle, cushioned from the stark anonymity of the modern city looming outside.

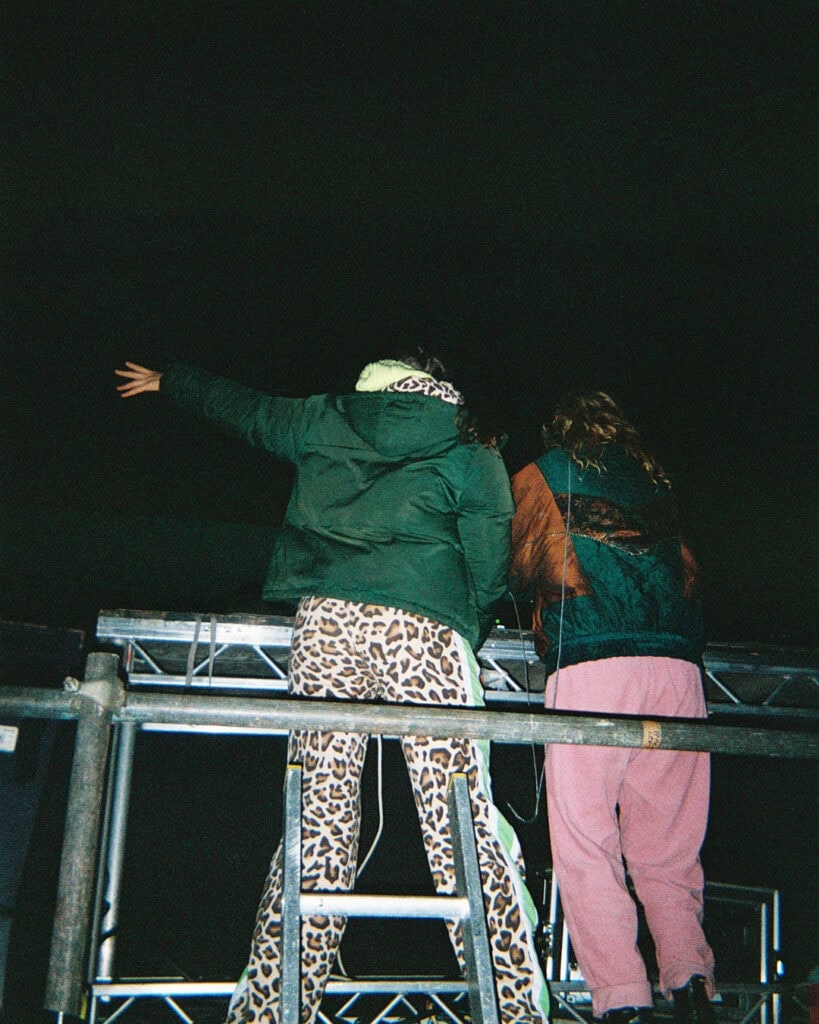

“This is the best warehouse district in London – Hackney Wick is gentrified now,” says a goth couple relaxing with me on a sofa, taking a break from dancing to our friend’s DJ set.

Not a lie was told. Harringay hasn’t lost its free, hedonistic charm. My springtime was still spent observing a dude dressed as Minion tumble around my garden smoking a DMT pen. But it isn’t immune to the predicaments that blighted Hackney Wick.

So, what did happen to the warehouses? One developer shamelessly told the 2019 documentary The Wick: “It’s your job as artists and musicians to make places like this cost more. And that’s where we come in.”

Rent for windowless box rooms has unjustly soared, pushing out the troopers who kept the party going. Contracts got signed to redevelop some units into flats, squashing the DIY spirit that made the lack of radiator worth it – I can almost get behind the “Make the Warehouses Grim Again” cap that’s been circulating. And maybe a cooler spot has cropped up that everyone is gatekeeping from us. Bristol, Margate? Deptford?

The warehouses sit somewhere between a commune and a co-living. It’s an intentional community centred on building meaningful relationships – but you aren’t exactly handed a scripture of utopian principles and told to quit your job to plant cabbages on an organic farm. It’s loosely anarchistic, but not by design.

Social media is obsolete – why add your sort-of-hot neighbour on the ‘gram when you won’t be able to avoid them at the under the sea-themed bash on Friday night, possibly on a half gram? Now that’s organic. In a modern city, graduates fight for a slot in each other’s social calendars and yearn for the days of bumping into their crush around campus.

Prior to it becoming residential, Maynards wine gums, pianos and orange juice were produced there from the early 20th century. Back then, Britain answered to the sobriquet “workshop of the world” for leading the Industrial Revolution. From the 1970s onwards, manufacturing dwindled.

Instead of emptying out into a ghost town, Harringay got populated by extraverts who prefer constant company to personal space. Beginning with just open-plan floors with no separate bedrooms, they crafted it into a home. They pulled together enchanted forest theatre set design and furniture picked up off the street (and checked for bed bugs).

For staunch warehouse veterans, once it dies they’ll start over in a new industrial unit. For others, it’s a temporary rite of passage: a crash course in handling the good, the bad and the ugly of human nature. During my time there I met indelible fire breathers, rune readers, blacksmiths, hyperpop musicians and ukulele enthusiasts. The community is blessed by love, solidarity and friendship, but also marked by addiction, theft and infestations.

For me, it’s a familiar place I return to when I need solace. Walking through that gate feels like a hug, and I know I’m not alone. Spaces like this deserve to be protected by the council, not demolished for gluttonous redevelopment plans disguised as “making it viable by funding it via regular residential units.”