Lost was a dream – now it’s coming to an abrupt end. Maybe it had to be ephemeral; after all, the candle that burns twice as bright burns half as long.

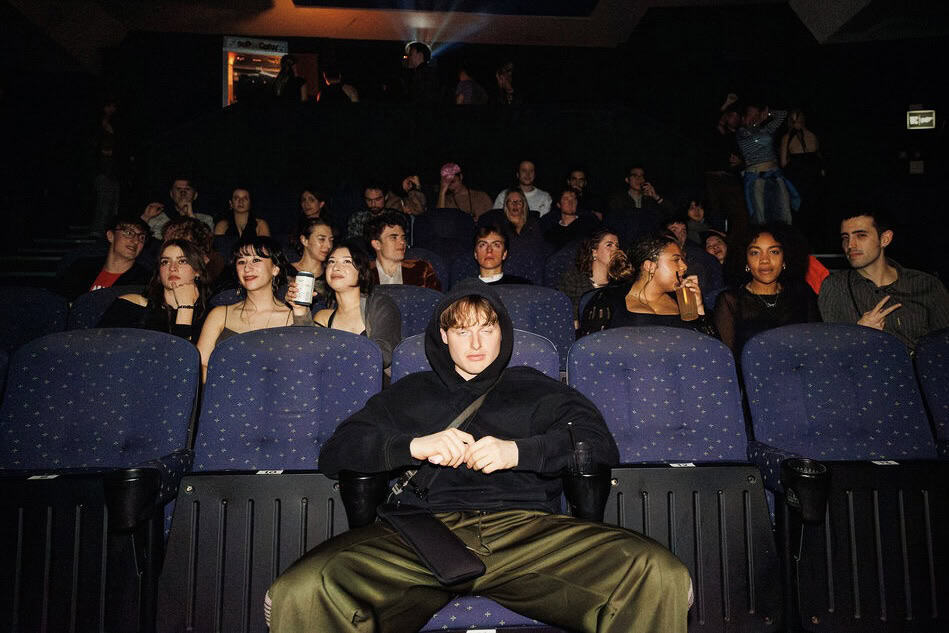

The immersive cinema-nightclub, launched in late October, transformed the former Saville Theatre-turned-Odeon into a “sanctuary for artists, audiences and dreamers.” And for a very special, short time, it was. This month, its interior is set to be gutted to redevelop the building into a hotel and circus. The collective has promised to find a new building to occupy and revive.

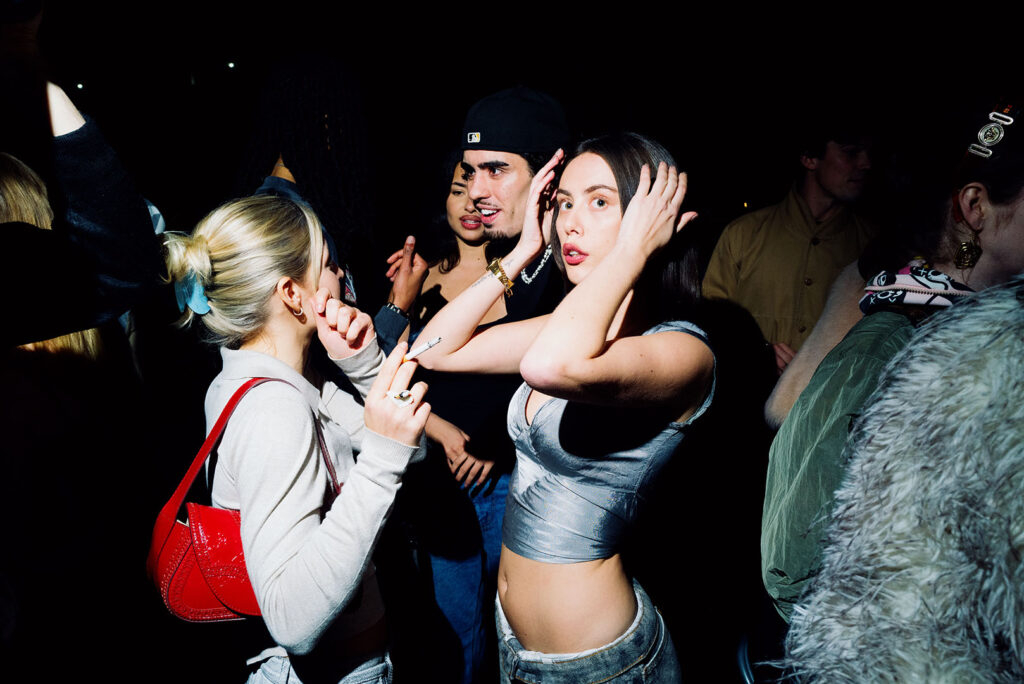

Despite its minimal online presence, word of a nightlife revival spread like news of a London Fashion Week afterparty. A generation hungry for “real” experiences got infatuated with a nightclub where phones didn’t simply get a sticker over the camera but got locked in sealed pouches.

Lost is onto something. And for a few weeks, they seemed to have it. They banned photography and refused to talk to the press, but the city was hooked. Less than two months after launching, pictures were splattered across Vogue, The Face, The Times and Time Out. People who hadn’t been clubbing since university were suddenly excited to go out again.

But we live in a capitalist hellscape. London eats its best ideas – an unselfconscious art-for-art’s sake club environment is tough to achieve, and even more so to keep up.

The moment a genuinely cool project emerges, it has a lifespan of a mayfly. Soho House is a prime example: it got overhyped, went from a place for artists to a place for anyone with an “artistic spirit”, then became a parody of itself.

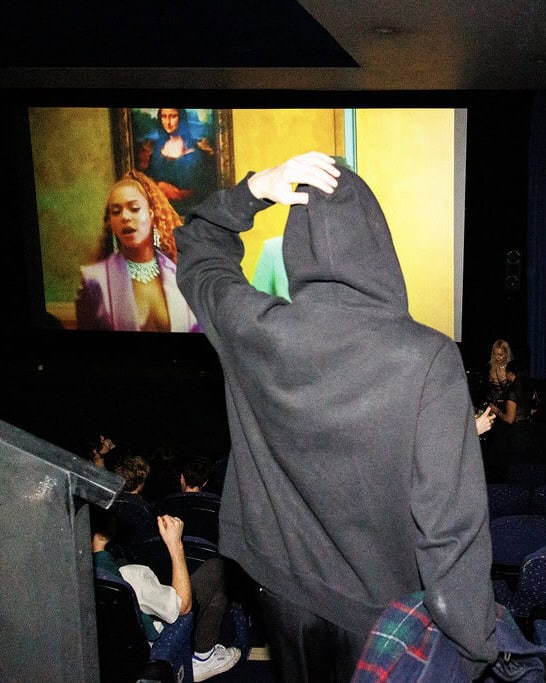

“The Lost founder” came up with his other project, Secret Cinema, as a child who “wanted to live inside the film”. He made his career crafting simulations of places so that audiences can feel like someone else, somewhere else, for a few hours.

The last time I was at Lost, Tom Willis – founder of Soho Reading Series, which he was hosting there – kept telling us how cool the venue was. But as I tried to lose myself in the labyrinthine maze of experience, revelling in the Lynchian dreamscape that, on previous occasions, had carried me through the night to the next day, I found myself feeling self-consciously awake.

Lost tried to create an unseen utopia where one could live fully in the moment.

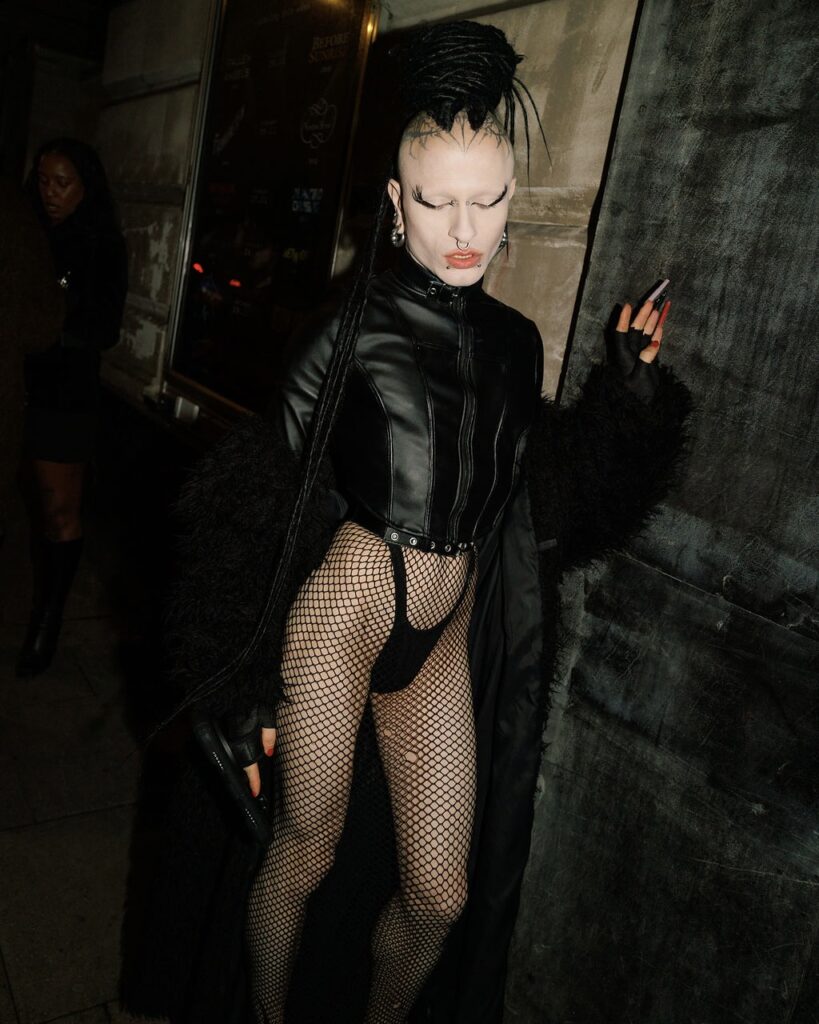

By the end of the two months, paparazzi lined the smoking area and were posing girls up by the wall in full view. We accidentally walked through a full-equipment video interview. Everyone seemed hyperaware of the potential of ending up on socials the next day, instead of Lost in the moment.

A bouncer guarded one of the rooms, turning people away as it was “shut for a private event”. To enter another, I was asked if I had a gold wristband. The powder room was full of people pushing to get into a stall. The smaller DJ booth room was vacant. Nothing was playing on the screen in the Lost theatre – although people sat expectantly in their seats as the chalk timetable had, between scrawled Instagram and Tiktok handles, suggested that something was supposed to be on the screen.

Lost is very possibly inspired by the incredible Fàbrica de Arte Cubano (FAC): an artgallery-theatre-nightclub-venue-bazaar in Havana, Cuba. It was built in an abandoned cooking oil factory and named as one of TIME’s 100 World’s Greatest Places. There are absolutely no photos of the inside – even the one in TIME is from the daytime, and provided by the venue.

But the iconic Cuban club exists in a place with no real hope for social mobility, which creates a wholly different art-for-art’s-sake club environment that London can only dream of.

The last time I was at FAC was a genuinely spontaneous lost-in-moment tropical night. I met a lady in a mosh pit who made me a shirt. I trailed her from the rock band hall, past an experimental film, down the stairs and through a photography exhibition. We found ourselves in a cave with a hip-hop cypher and then her shop. She biked the finished garment over to my AirBnb the next day. We shared a cigar overlooking El Capitolio.

Lost, by comparison, is like Plato’s cave. You’re at the hot new cave. It’s dark. You’ve never seen the sun. You’re chained up. A puppeteer throws shadows against the wall in front of you. London’s nightlife has been so dead since the pandemic that you mistake these shadow images for The Real Thing. “Wow,” you say. “I’ve been clubbing my whole life and never seen anything like this.”

Lost is onto something. Multiple trend forecasters report that clubs housed in disused urban spaces, promising “real” experiences, are the next big thing in London. From a soft porn cinema in Pigalle (Paris’ red light district) – to statements like “together we will open all the lost theatres”, Lost has posted photos to Instagram alluding to its mission.

Excitement around a nightclub is hard to come by at the moment. One in four UK late-night venues have shut since 2020, a figure that accounts for more than 3,000 defunct clubs in London alone. The number of pubs, bars and clubs holding a 24-hour alcohol license have fallen by two-thirds in the past two years, according to a report by Bompas & Parr – a rate that, if it continued, would see no nightclubs left in the capital by 2030.

But as the coolest thing we’ve got going in a city always looking to consume, Lost could burn out if it doesn’t learn to regulate better. I hope, in its next iteration, Lost doesn’t lose itself.

(From @lostclubnight’s Instagram stories. A mostly empty soft porn cinema in Pigalle, the red light district of Paris, and the exterior of Lost nightclub, a disused Odeon cinema in what was once the historic Saville Theatre)