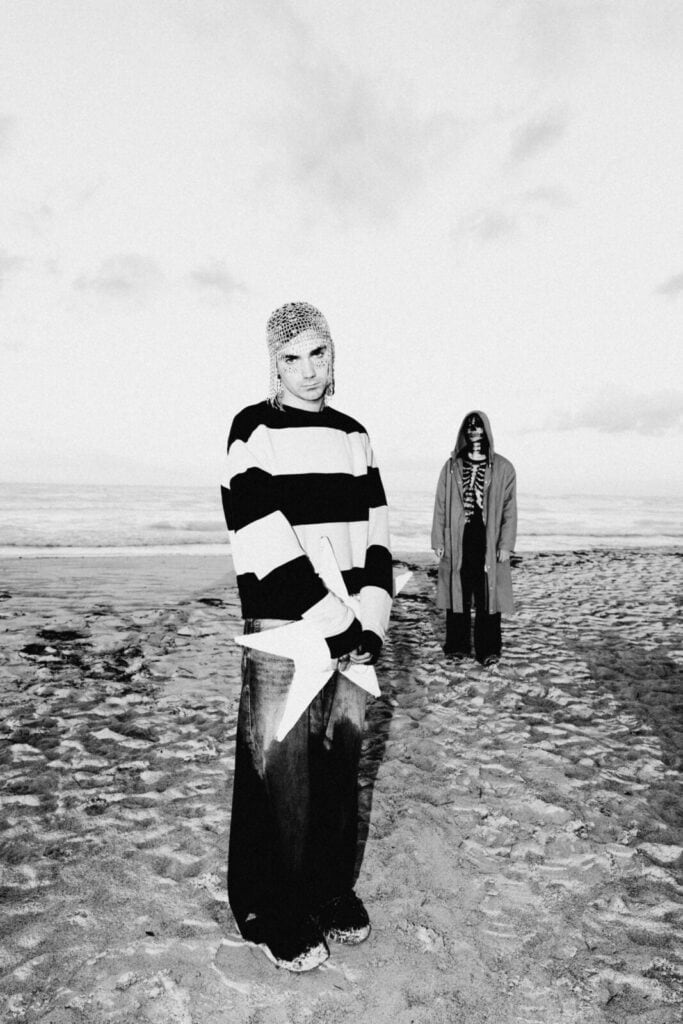

With Stellar Boy, Piccolo builds an emotional and visual universe that moves across music, drawing, and storytelling. A hybrid project, suspended between memory and dream, where the album and the graphic novel speak to each other as two sides of the same inner experience. At its center stands a fragile, masked character in constant transformation, becoming the core of a broader narrative about how we can tell our own stories without ever fully exposing ourselves.

Interview with Piccolo — Stellar Boy

Stellar Boy sounds like the name of a character even before an album. Who is this “stellar boy,” and when did you realize he could become the narrative center of the project?

Stellar-Boy is an alter ego of mine, mixed with the reflection of some people I know who have influenced me. He’s a clumsy character wearing an elegant Venetian mask, lost in a limbo between the dreamlike and memory. He first existed as the subject of an illustrated story, which then needed a sonic counterpart and that’s how the album was born.

The graphic novel accompanies the album like a second layer of reading. What is the relationship between the drawn story and the tracks on Stellar Boy? Are they parallel narratives, or the same story seen from different angles?

I’d say they are two different points of view on the same story or the same narrative experienced through two languages: visual and sonic. They share similar settings, and both talk about the same period of my life. I’m someone who struggles to be too direct, so I prefer to communicate through metaphors, twisted sentences, and a certain surrealism.

In Stellar Boy deep fragilities emerge, but there’s also a certain emotional distance. How much does this character coincide with you, and how much does he help you step back from what you’re telling?

To stay on theme I’d say “fifty-fifty,” but honestly I don’t even know the real percentage. Sometimes alter egos just like albums feel more like children to me: they’re born from a facet of my personality, but then they walk on their own legs. He helps me create distance from certain things I say, things I might never say out loud but that somehow need to be expelled from my body.

Drawing allowed you to visualize emotions that remain more abstract in music. Were there moments in the album that you only truly understood after putting them on paper?

The comic and the album inspired each other, even if the first impulse came from drawing. In general I like to visualize everything I do music videos, sets, clothes, environments. It’s an exercise in manifestation: it helps me clear my head and, above all, to make what I desire come true. And yes, there were moments in the album that I only understood how to communicate in words after drawing them.

The project’s aesthetic—between UK references, indie imagery, and graphic storytelling—is very coherent and recognizable. Did it emerge from the music, or did it also guide the writing of the album?

For me, imagery always comes first. I like to start from a concept, a color, a cover—it helps me choose words, sounds, and atmospheres and stay coherent. I try to mix as many arts as possible to look at things from different angles, but also simply because it’s fun. The aesthetic then took shape along the way, through a very hands-on process, from the comic to the music, all the way to the masks and styling.

Compared to your previous work, this project feels more narrative and layered. Do you feel Stellar Boy marks a maturation in the way you tell your story?

Yes. With this project I managed to raise my own personal bar again, and for me that’s the biggest achievement. Stellar-Boy was very difficult to conceive, but it definitely brought me to a new level of maturity. The next step will probably be something no one expects.

The album and the graphic novel build a whole universe. Do you see Stellar Boy as a closed project, or as a character that could keep evolving, maybe even through other languages?

I wouldn’t call it closed. For now, the aesthetic has been set, and now that it has a clear identity and a unique universe, it can walk on its own. What happens next is impossible to know maybe in a couple of years some director will have a vision and we’ll take it to Netflix, who knows. I’ve stopped asking too many questions about the future.

Building such a personal and layered project also involves risk. What was the hardest part to leave exposed in Stellar Boy?

Definitely the fragilities that come out through the writing, which now everyone can hear. But also the courage to post or show certain drawings. Detachment is the most important step for an artist: when you learn to create distance and share your inner journeys with others, you do good for yourself and for them.

The album writing and the work on the graphic novel influenced each other in terms of time and process. Was there a moment when one language took control over the other?

At first I didn’t really understand what was happening and I was carried by instinct and flow—things were being born and I just let them happen without forcing them. Then I realized the connection between what I was drawing and what I was writing, and I started to visualize the final outcome: I wanted an album and a comic that spoke about the same experience from two different points of view. In the end they always went hand in hand—music took over in the final phase, but in the beginning it was definitely drawing.