When my Zoom call with Bryn Chainey finally connects, there’s no audio. If any speech does come through, it’s garbled at best, inhuman at worst. Several minutes of hang-ups and call-backs later, we finally get to speak with one another, and our interview begins with a slight distrust on my end that Zoom would even be recording the call at all. Technology, it seems, is not our friend.

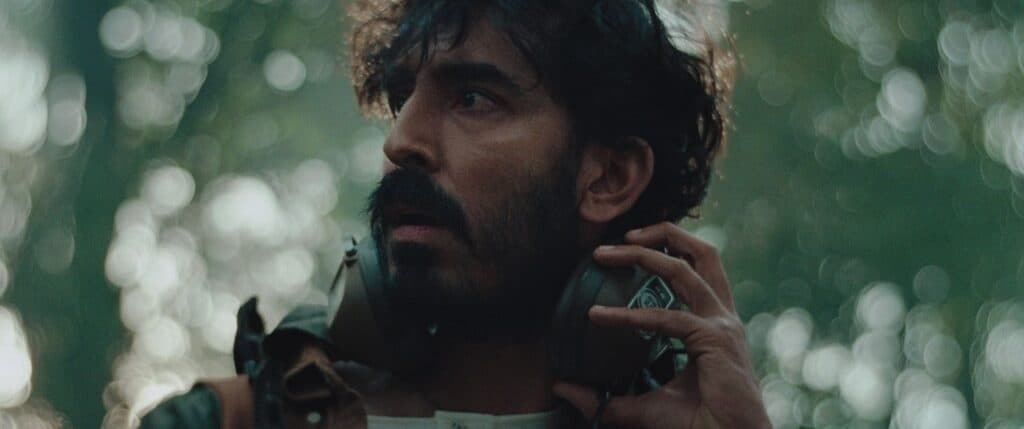

We’re calling to discuss Chainey’s feature debut Rabbit Trap, a folk horror film set in the Welsh countryside of the 1970s. Starring Dev Patel and Rosy McEwan as married couple Darcy and Daphne, it follows the pair as they move from London into a remote cottage. Daphne is a musician, a character fashioned after the female pioneers of early electronic music, and she’s searching for inspiration in the natural landscape – a world of wind, moss, and howling. Darcy, her sound engineer, ventures into the landscape to record her audio, but as he drifts outward he begins to pick up a strange sound, something like a song. And so a door is opened.

Inspired by his lifelong love of folklore, Chainey delves into the world of faerie through the appearance of a strange child: possibly ageless, somewhat genderless, and with a feral edge (played by Jade Croot). As we discuss in the interview, children recur throughout folklore for their proximity to “the other.” Chainey speaks about fairies and goblins as volatile, wounded forces – the parts of ourselves abandoned early, left to grow wild. In these child-figures, he finds a rich psychological language, and with Rabbit Trap crafts an intimate story of trauma unravelling and uncoiling.

Arriving amid a renewed interest in folk practices and folklore, Rabbit Trap doesn’t treat pre-Christian mythology as something inherently scary. Instead, as Chainey explains, it approaches these belief systems as vital and capable of healing. It certainly charmed me. And by the end of our laggy, fractured Zoom call, I couldn’t help but think that perhaps the faeries themselves were interfering with our Wi-Fi, meddling in our recording as they do with Daphne’s music.

The Cold Magazine (CM): Tell me about how the movie started. What drew you into Welsh folklore specifically?

Bryn Chainey (BC): The short film that I’m most proud of was also a fairy-tale-style film. I did it in Germany in 2013, it’s called Moritz and the Woodwose. That short is also about repressed memories, stumbling upon ancient folkloric powers in the woods, and those forces being part of a journey of self-discovery. I found that it was a story I needed to tell better, and more comprehensively. I know it’s been said that filmmakers just keep making the same film over and over again from different angles, and that’s probably what I’m going to do for a while – keep riffing on self-revelation through nature and through magic.

I think my first interest in Welsh folklore came from my dad. He’s Welsh and my mum is English, and I grew up just knowing about fairies, goblins, pixies, creatures like that. It was all in the children’s books we were given. I learned about pixies and fairies at the same age I learned about Father Christmas, God, and history.

There’s that time as a kid when you’re being told about events or characters you’ll never experience yourself, but you’re told they’re real. You go, okay, that’s true. And then there’s a man who comes down the chimney and brings you presents – okay, cool. And then there are fairies who live in the woods.

As you get older, you become disillusioned: there’s no Father Christmas, there’s no justice or democracy, or whatever it is. But still, somewhere deep down, they remain true. That was a long-winded answer, but since childhood I’ve thought of nature as being slightly conscious, and that consciousness is expressed through these creatures. It’s a way to understand nature, and a way to understand parts of ourselves that might be hidden from us.

CM: It makes sense to personalise nature through mythology. I think there’s a lot of possibility for self-revelation in these stories, especially because so many involve children. Children are swapped or kidnapped far more than adults. Was that something you were thinking about when making the film?

BC: When I decided to hone in specifically on Welsh goblins, there were a few research texts I leaned on. The biggest one was a book called British Goblins, published in 1880 by American journalist Wirt Sikes. He travelled around Wales interviewing people who had seen fairies or goblins. When I say fairy, I don’t mean Tinkerbell or some little winged child. I mean a ghoul, a bogey, or even a force. Fairy is also a place, capital-F Fairy, where elemental spirits live.

Sikes compiled these accounts, and there’s very little consistency in goblin behaviour. Sometimes they’re seductive and want to be part of the human world. Other times they want to drag humans into theirs. Sometimes they punish people for the smallest things, like not giving them enough attention, or breaking some arbitrary rule. They’re volatile and easily offended.

The consistency I found was that volatility, that reactionary quality, which felt very childlike to me. It shifted my perspective. I began thinking of goblins and fairies as the wild twin we all lose at birth. There are cultures across Europe that believe when you’re born, part of you enters the world, and part of you is cast out, thrown into the woods. That part grows feral. It survives on cunning. It grows claws and fur. Its eyes darken.

And part of the journey of self-actualisation is to go into those woods – the forests of our consciousness – and find that wild twin. Not to kill it, but to bring it home. To integrate it.

So that became my interpretation of fairies: they’re the parts of us that were cast away. Once I found that lens, Rabbit Trap locked into place. It became about an inner child that was wounded long ago, abandoned into the wilderness, and has grown strange, feral, hungry.

CM: I was also thinking about how, in pre-Judeo-Christian belief systems, gods were so human – petty, jealous, disastrous. Greek and Roman mythology especially.

BC: Yeah, and it’s the same in the Old Testament. Yahweh is petty and jealous. He literally says, “I am a jealous God.” The first commandment is basically “I’m the best, only me.” It’s very childlike. “Me, me, me.” They need that attention to live.

CM: So I wanted to go back to Daphne and Darcy: your choice to make them musicians, and the importance of sound. I loved how sound became such a visual and visceral character in the film.

BC: Sound came a little later. I always knew I wanted a couple confronted with Celtic fairy forces, and I knew madness, or the boundary between creativity and madness, would be part of it. There’s something inherently mad about wanting to create.

I considered different kinds of artists, and sound emerged through further folklore research. Music is central to Welsh fairy encounters. There’s an account in British Goblins of a man who saw a procession of goblins singing through the valleys. He said it was the most beautiful song he’d ever heard, but he couldn’t remember the melody afterward. It was forbidden to be remembered. That fascinated me. It connected to repression, memories you can’t access. The man remembered the words, though, and those were written down. We used those words as the lullaby the child sings in the film.

Music felt like the door into Fairy – not a visual door, but a sonic one. That also lines up with people I’ve spoken to since releasing Rabbit Trap, including paranormal investigators. Many feel the film reflects real experiences more accurately than most. One podcast host I spoke to – he’s interviewed hundreds of people about ghosts, Bigfoot, aliens – believes the supernatural isn’t allowed to be seen. You can’t photograph it. But sound is allowed. You can capture something with sound.

That idea has a long history. In the Bible, encounters with God or angels are often voices. God appears to Moses as a burning bush and a voice. You’re not allowed to see God, it would destroy you, but you can hear Him.

CM: It seems that public interest in folklore keeps resurfacing every few years. It’s certainly popular at the moment. Why do you think it has such staying power?

BC: I’ve thought about it before, and the one thing I can say is that with Rabbit Trap, in terms of it belonging in that folk horror landscape, I wanted to do something a bit differently.

I didn’t want to treat fairy forces or pre-Christian Celtic mythology as demonic, or as something to be overcome or defeated. That’s a big trope of folk horror, and it doesn’t really jive with me – the idea of an Englishman going into the countryside and encountering rural folk who are backwards, or screaming, hysterical fairy figures that need to be destroyed. That doesn’t line up with my research, and it doesn’t line up with what I want to say about Celtic identity. You mentioned pre-Christian mythologies earlier, and I think a lot of that negativity toward so-called “pagan” belief systems is a leftover from when the Romans came in and demonised the native Britons and everything they believed. We’ve never really undone that.

So something I’m trying to do with my films is present a landscape of Britain that predates Roman and Christian invasion, and to restore some dignity to those beliefs, not treating them as relics that haunt us, but as something vital and natural to the land, and something that can heal.

It treats all the characters as wounded creatures who share a longing to belong, and to be loved. That was a very conscious decision, even though it probably means the film doesn’t have as big an audience as it could have.

CM: Something else I wanted to ask about was gender. Daphne is such a pioneer figure, but at the same time her work keeps her at home while Darcy explores the landscape. And then there’s the child – played by a female actor but presenting as male.

BC: With the child, the way we approached it was as an ageless, genderless, species-less being. But for the story to work, and for the child to get what it wants, it presents as a boy – because that’s what allows Darcy and Daphne to trust it.

If this creature had shown up as a girl, they’d have had far more questions: Why are you out here alone? Where are your parents? But you encounter a feral little boy in the countryside and you kind of go, This is just what boys do. So it made sense for the character to present as male, and for that ambiguity to remain unsettling. There’s always a question mark: who are you really?

Maybe one in ten people have been angry about the casting, saying they were distracted because it was a woman playing the role. But that says much more about that audience member than about the film. We suspend disbelief for almost everything in cinema except, for many people, gender. And I find that really telling.

As for Daphne: she’s the breadwinner. She’s the genius. Her name is on the records. Darcy is her engineer and assistant.

There were a few things I wanted to do. For one, I don’t see enough married couples in cinema who actually get along – who are still hot for each other, still connected physically and emotionally. I wanted to show a couple with real communication problems, but who still have love and sensuality between them. Daphne is also based on real women, pioneers of electronic music like Delia Derbyshire, Daphne Oram, Suzanne Ciani, Laurie Spiegel. These were obsessive women who were often labelled “difficult.”

I wanted to pay tribute to them. Her personality had to match that intensity. Delia Derbyshire, for example, was an alcoholic for a time, lived in the countryside, took a younger husband, was controlling, there are great books about her. I wanted to reflect some of that complexity. For me, it also just reflects my own experience. I’ve almost always been in relationships with creative women, and the dynamic is very different from the standard masculine/feminine roles you see in films. It’s more fluid – who earns, who leads, who supports, who struggles.

I wasn’t trying to make a statement so much as reflect reality, the reality of artistic couples and the tensions and tenderness that come with that.

CM: I thought the relationship felt very real – tender and tense at the same time. I loved the bathtub scene.

BC: That’s my favourite scene too. And Rosie [McEwen] was incredible. She didn’t even know her hair was curly until we shot the film, I taught her the curly-girl method. I’m obsessed with curly hair. Rosie was thrilled when she realised she’d had curls hiding there all along.

CM: I keep seeing the word “trust” used in writing about the film: trusting actors, trusting audiences. Is that something you consciously think about?

BC: Yeah, trust is huge. Trusting the audience to interpret, to dream – David Lynch calls it “room to dream.” That’s what I crave as an audience member. When a film leaves no room for imagination, I feel disappointed.

But it’s a balance. You don’t want to strand people completely. Throughout writing, shooting, and editing, we were constantly asking: Are we giving too much exposition? Too little? Are we patronising, or being obscure? I actually thought I’d over-explained, but once the film started playing, many people felt it wasn’t enough. That’s something I’ll always be working on.

CM: Finally, I wanted to ask about the landscape. What was it like working so closely with nature?

BC: Location was huge. We couldn’t afford sets, so everything had to be real. The house needed to be accessible, remote, and run-down enough that we could trash it more. It took nine months to find. We ended up shooting in North Yorkshire, near Harrogate, even though the film is set in Wales.

I love films where you feel the landscape, where you feel muddy, damp, cold. That was a priority. And the shoot really was like that: foggy, drizzly, muddy. Nature forced us to adapt. There was a whole sequence involving an overturned tree, called “the old hag”, that we just couldn’t find. So we rewrote it on the spot, turning several fallen trees into a kind of chorus. That’s just one example of nature reshaping the film.

The weather gods were kind to us. Nineteen-day shoot. Eight days outdoors with clear skies. As soon as we moved indoors, torrential rain hit. Perfect timing. Maybe some entity liked the script.

CM: Maybe the fairies.

BC: Exactly. If they weren’t pleased, they’d come for me.