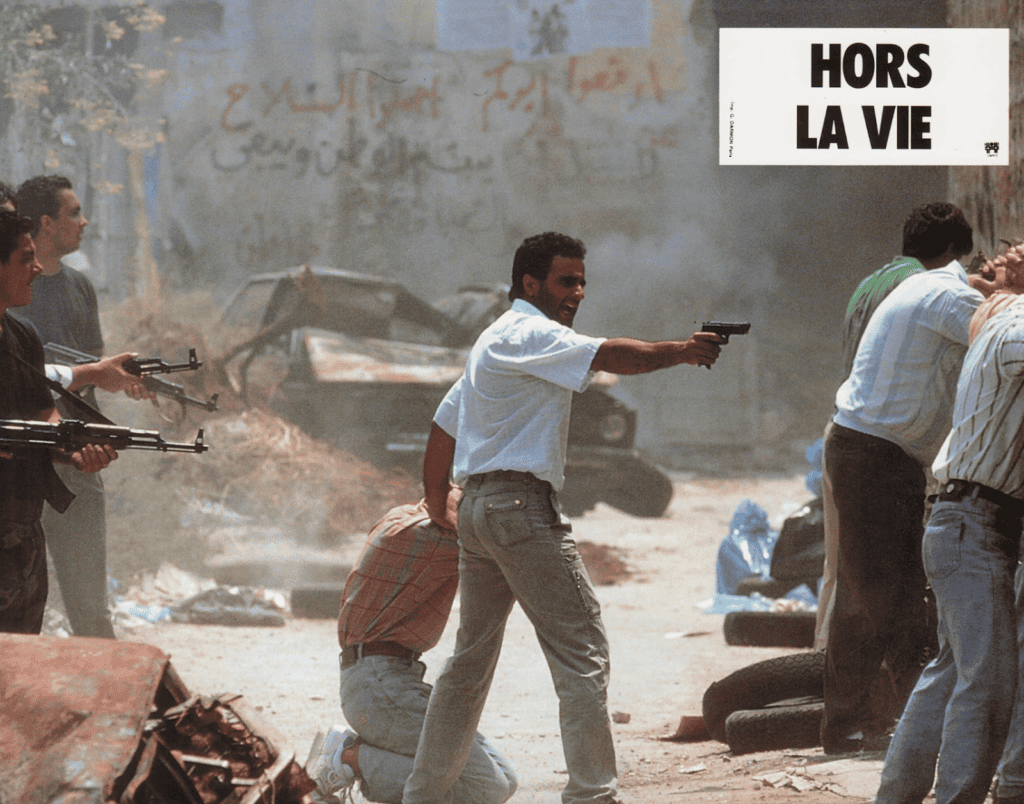

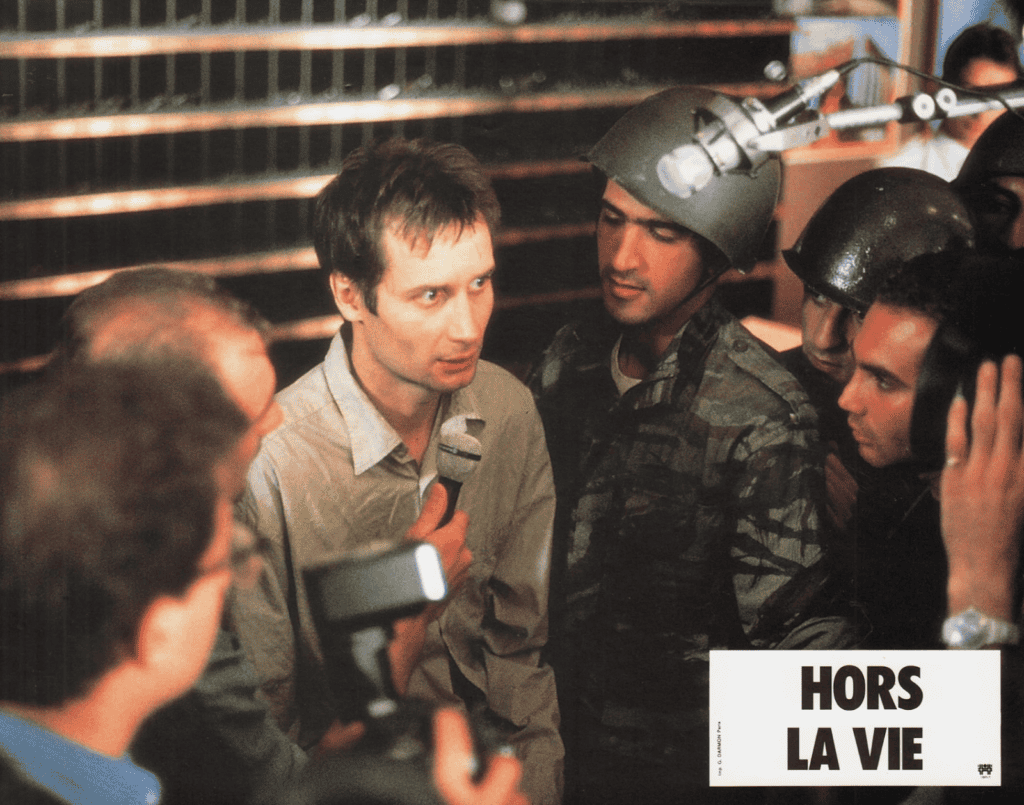

In the era of constant coverage, the visibility of suffering in asymmetric conflicts across the Middle East and Africa – such as that of Gaza or Sudan – remains politically opaque. With technology allowing wider, grassroots coverage, clarity continues to be obscured by conflicting political claims. Nowhere is this conflict better captured than in Maroun Baghdadi’s Hors la vie (Out of Life, in English), a film that typifies the tension between suffering and political meaning: in content, in form, and in function. Indeed, Hors la vie has come to represent a contested site of memory for Lebanon and its defining civil war.

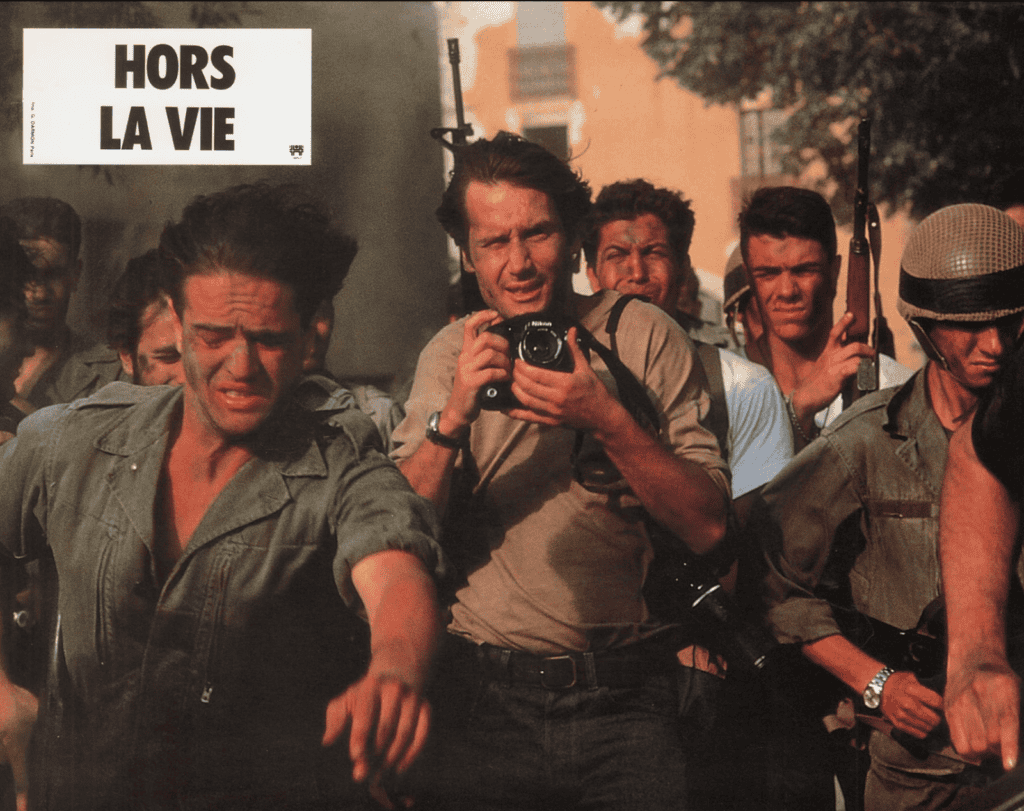

Released in 1991, the film tells the story of French photojournalist Pierre Perrault, who, while

covering the Lebanese Civil War, is abducted, detained, tortured, and exchanged as a geopolitical bargaining chip. The plot is largely inspired by the kidnappings of various Western figures, including academics, diplomats, intelligence officers, and journalists, during the height of the conflict. Perrault in particular closely resembles French journalist Roger Auque, kidnapped in Lebanon in 1987 and a figure long rumoured to be an Israeli spy – a fact confirmed in 2015.

The revelation of his espionage exemplifies the potential for political actors to manipulate conflicts in unstable regions such as the Levant.

Centering the narrative perspective of a Frenchman opens the film up to orientalising criticisms, exacerbated by notable omissions: namely any reference to the indelible history of Franco-Lebanese relations or French mandate of Lebanon. And while the war has been the subject of Lebanon’s national cinema, Baghdadi’s cinematic preoccupation with the war climaxes in a work in which one (foreign) man’s personal ordeal prescribes meaning to a nation. In many ways, this focus undermines the broader scope of his filmography, which explores the tragedy of Lebanon and its citizens trapped in cycles of conflict.

In fact, Hors la vie stands incongruously in Baghdadi’s work, a cinematic enterprise steeped in conflict and identity amid competing ideologies, enduring division and national uncertainty. His tragic death shortly after the fragile placation of warring sects has only reified the prevailing message of his work: an insistence on pluralism over futile sectarian conquest. From this perspective, Perrault is not an apolitical spectator but a political actor whose presence shapes the international perceptions of the war and even the course of events.

Even so, Baghdadi was uniquely positioned to pursue his work. Dividing his time between Lebanon and France, Baghdadi established himself early, gaining access to industrial support through foreign investment and transnational co-productions. Though his work focused on Lebanon, it is important to note Baghdadi’s ability to navigate film production in East and West, with his success in France likely shaping the international perspective of the film.

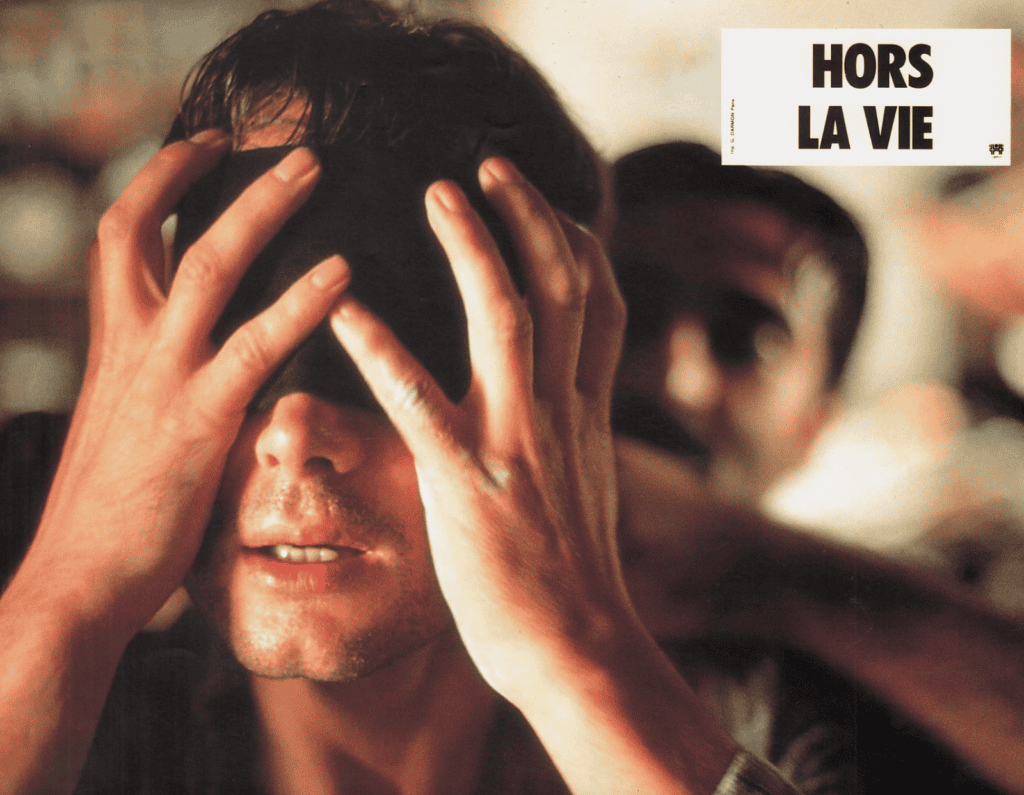

Hors la vie is marked by its notable deviation from Baghdadi’s earlier work, which explored and challenged Lebanese national identity. The film is distinctly unsentimental and impassive in its depiction of the physical and psychological toll exacted on one man – notably, a Frenchman – a

choice that is clearly intentional. The film avoids explaining the conflict, its combatants and their

history, instead placing us within temporal confinement – only seeing what is shown. We are, much like Perrault, subject to the shifting dynamics of the parties involved. In this way, the austere portrayal of the conflict prevails in capturing the unpredictable nature of political negotiation. Finally, much of the runtime concentrates on Perrault’s captivity.

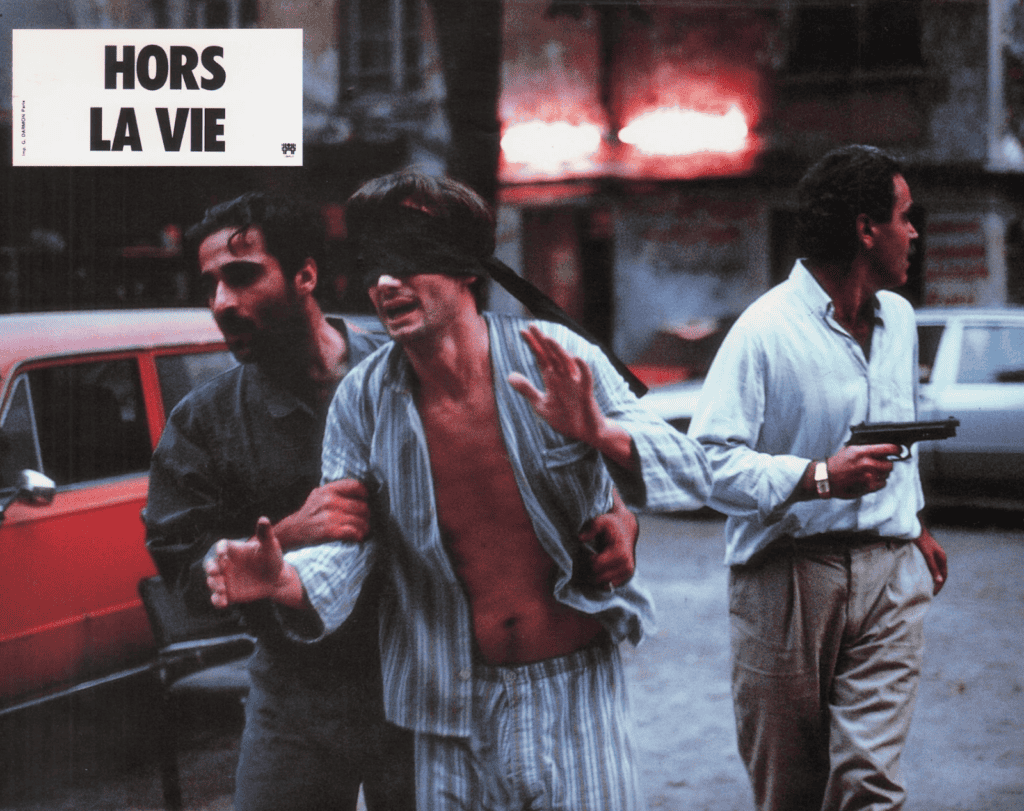

Perhaps the most striking motif is Perrault’s transportation across enemy lines, concealed in a series of makeshift positions. From one location to the next, Baghdadi introduces a revolving cast of captors, reinforcing their uniformity despite conflicting political claims. While the victimisation of the Frenchman remains at the fore, Baghdadi hints at the humanity of Perrault’s captors through their ideological entrapment and their thwarted personal aspirations. The carousel of captors further functions to emphasise parallels, from one militiaman’s desire to become an actor to another’s wish to learn French. Baghdadi is attentive to the men behind the militias, not flattening them into terroristic tropes but presenting them as caught in a national conflict they help reproduce, yet hope to escape. The potential to depict a nuanced moral economy within the war is never fully realised, circumvented by Perrault’s resolutely coded victimisation.

Indeed the opening of the film features a procession of mourning women holding photos of their deceased – an event that quickly descends into chaos and, for Perrault, creates content for capture. Perrault is unmoved by the horrific sights of mangled bodies, emotional devastation and frequent death; he is insistent on taking photos even when urged not to. He is steadfast and committed to the pursuit of documenting violence – rushing into the line of fire with a horde of gunmen or photographing street executioners, mere feet away. Perrault shows no signs of fear. On the contrary, he is confident, bold, even courageous in the face of danger.

That is, until he is confronted by two militiamen who insist he photograph them by a hanging corpse – a command Perrault is reluctant to oblige – soon after, ripping out the film and discarding it on the floor. A close-up shot of this discarded film ominously presents the title card “Un film de Maroun Baghdadi” (‘a Maroun Baghadi film’). Such a formal creative choice reiterates Baghdadi’s precision and serves as proof of Perrault’s moral conscience; indeed, he is just heavily invested in his work. The power Perrault possesses in this instance is, however, important to note, holding in his hands the ability to determine the story that is told – not the natives.

Which leads us back to the figure on whom it was freely inspired, Roger Auque. Abducted in 1987, Auque’s 319 days of captivity came to an end through political intermediaries that negotiated his release. Auque would go on to write Un otage à Beyrouth (A Hostage in Beirut) – forwarded polemically as an account of the “torment that innocent prisoners in Lebanon are enduring” outlining the conditions that would later be emulated in Baghdadi’s film. Much like the film, it is his suffering at the centre of the film’s construction. And whilst this form of self-narration is not inaccurate in book nor film, its authority is challenged when Auque revisits it decades later.

In his autobiography Au service secret de la République (In the Republic’s Secret Service), he states: “Today, I am revealing my dark side. I was not just a journalist; I was paid by the Israeli secret services to carry out certain missions…” going on to further state “As I have already said, I have always had a great need for money. My dark side was not limited to the Israeli services. I also worked for the French.” Such an account emphasises the epistemological fracture in spectatorship – usually legitimate grounds for critique that becomes a form of symbolic violence when compromised.

Hors la vie is a stunning, visceral piece of cinema. The technical achievements in recreating the gripping account of Roger Auque are deserving of the praise the film received at the time of its release. Yet, Hors la vie sits out of place in Baghdadi’s contemplative and prescient tapestry of a divided Lebanon. The film is a product of Baghdadi’s maturing aesthetic proclivities that outgrew partial sentimentality or undeserved emotionality.

The film’s intended function can at best be understood then through a post-Orientalist lens, as one that holds a mirror up to the absurdity of Lebanon’s Civil War. Yet the personal ordeal – and the truth behind the inspiration of that ordeal – reveals a far more nuanced reality in contemporary conflicts. Similar to Perrault, we are desensitised in our consumption of these conflicts, drawn to the violence that erases native civilians who bear the consequences of the politically opaque. Hors la vie would go on to win the Jury Prize at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival – the first Lebanese film to win an award at the prestigious festival.