It’s a Wednesday evening, just after six, and I’m standing by the National Theatre stage door. It’s February in London, so naturally it’s raining. Water has crept up the fibres of my jeans to my knees, and my umbrella leaves a small but stubborn puddle on the floor. Inside, I’m asked to sign in and pose for a quick security photo. A printer hums and produces a sticker labelled Guest. I stick it to my coat, feeling, despite myself, faintly smug.

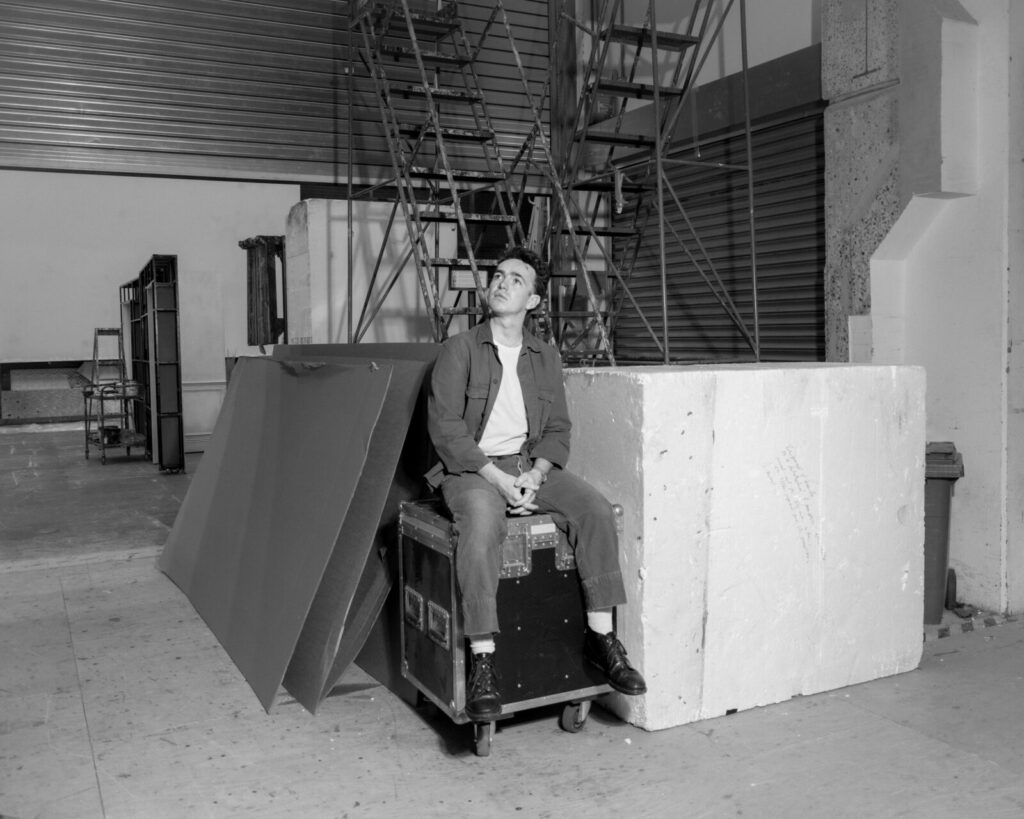

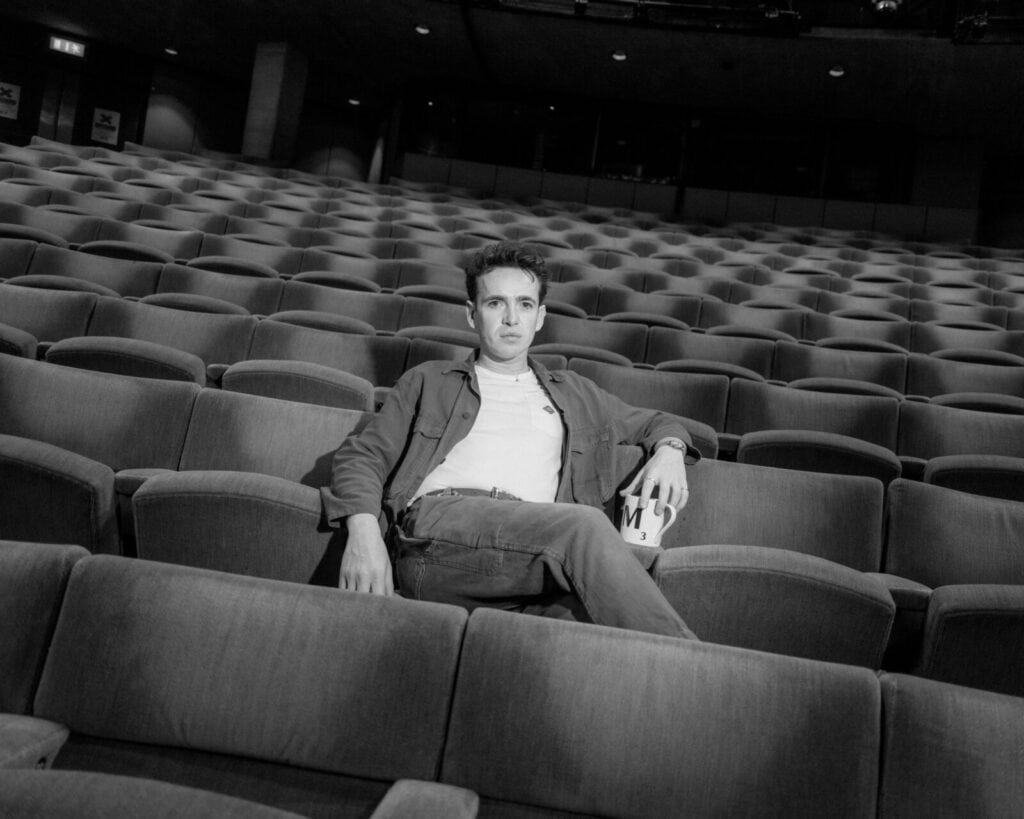

I’m here to meet Laurie Kynaston, who is about to make his National Theatre debut in Man and Boy. I’ve been to the theatre countless times before, understanding it as an audience member, but never like this, not behind the scenes, not in the spaces where the work actually happens.

Around me, actors, cast and crew drift in and out, pausing to wave and smile at the women on reception with the easy familiarity that comes from long rehearsal days and late performances. It’s hard not to think: what a place this must be to work every day.

I’m led through a sequence of coded doors, into an industrial lift, and along a stretch of narrow corridors before arriving at a small room where I sit and wait, notebook open, questions at the ready.

Kynaston appears a few minutes later, carrying none of the early-evening fatigue that usually settles over London at this hour. Dressed simply in blue jeans and a white T-shirt, he brings with him a calm, purposeful warmth. We begin talking almost immediately, with the comfortable rhythm of two people picking up a conversation already in motion.

Man and Boy, Terence Rattigan’s post-war drama, is preoccupied with power, inheritance, and uneasy paternal legacies. This production marks Kynaston’s first appearance on the Dorfman stage, thirteen years after his professional debut in The Winslow Boy at a regional theatre in north Wales. In the years since, he has moved between stage and screen, most recently appearing in Leonard and Hungry Paul and the Netflix thriller Fool Me Once, seen by more than 100 million people worldwide.

In this production, Kynaston plays Basil, a character caught in the fallout of his father’s ambition. As we talk, he returns to the careful characterisation the role demands, the shifting power between father and son, and the difference in discipline required for the stage rather than the camera.

Sitting opposite him, just the two of us in a small backstage room at the National, this kind of intimacy feels worlds away from the scale of the Olivier stage he is soon to step onto.

The Cold Magazine [CM]: You made your debut 13 years ago in another Rattigan play. How does it feel for your debut National Theatre show to be another Rattigan piece?

Laurie Lynaston [LK]: So that was The Winslow Boy, about 13 or 14 years ago, my first ever play. I was 18, on my gap year, and part of a youth group at Theatre Clwyd in North Wales, where I’m from. The production was directed by Terry Hands, former Artistic Director of the RSC, and they’d been auditioning in London but hadn’t found the right person. My youth theatre director encouraged me to go for it, so I did, and ended up playing Ronnie Winslow.

At that point I didn’t really know what I was going to do with my life. I thought about drama school, but I had very little experience and didn’t know anyone who’d taken that route. I grew up in rural mid-Wales, not an environment particularly focused on the arts, but I had a brilliant drama teacher and spent most of my free time in the drama studio, that’s really what sparked it.

So to now be making my National Theatre debut in another Rattigan play feels very full circle. That first experience feels both five minutes ago and a lifetime away. Working at the National is a huge deal for any actor and something I’ve always wanted to do, so it feels especially meaningful that it’s with the same writer who was part of my very first play.

[CM]: Gregory says at one point that love is “a commodity I can’t afford,” and later Carol suggests that what binds him and Basil might be “love, or contempt, or both – or neither.”

Those exchanges feel like the emotional centre of the play: Basil, and the audience, trying to work out whether a man so driven by power and self-preservation is actually capable of love.

How did you approach Basil in this dynamic, someone who has gone out on his own to escape this push and pull, but can’t help being drawn back in?

[LK]: Basil is told several times, usually by his partner Carol, that he dislikes himself or has a kind of contempt for himself. That’s quite a tricky thing to play because the exact reason for that isn’t explicitly spelled out in the text, so I had to dig into it and ask: why does someone feel that way about themselves? And how do you communicate that to an audience, not just through what other characters say, but through what’s going on internally, the inner monologue.

I think the best way to describe it is that his self-contempt comes from the realisation that he still worships his father, even though he desperately wishes he didn’t. He’s always lived in his father’s shadow. Gregor is so mesmeric, intense, and impressive that it’s very hard not to be drawn in by him. But once Basil begins to see that a lot of it is performance, that he’s a conjurer, a trickster, he feels both duped and ashamed of how much power that still has over him.

[CM]: The critic Billington connects Gregor to figures like Robert Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein – men whose power relied on the erosion of real intimacy.

Basil is pulled into that ecosystem of power without ever fully belonging to it. Did you find yourself thinking about contemporary parallels, not just monstrous figures, but the people around them who benefit, comply, or stay silent?

[LK]: I think audiences have always been fascinated by characters who operate without the same moral limits as everyone else. I’m not saying Gregor is simply “evil”, but there’s always been a curiosity about how people like that think, how they justify their actions, and how they’re able not only to get away with things but often rise to the very top and be treated almost like demigods. That fascination goes back centuries, it’s at the heart of so many stories, from Shakespeare to modern film, because we’re drawn to trying to understand what makes someone like that tick.

I wouldn’t go as far as calling him an Iago figure, but he is an extraordinary character. Not to excuse his actions, many of them are deeply troubling, but he has this ability to captivate a room and bend situations to his will. He’s incredibly skilled at constructing an image and persuading people to see what he wants them to see, which is part of what makes him so watchable.

In terms of contemporary parallels, he feels less like a single real person and more like the kind of powerful industrial figures of that era, the Rockefellers, the Hoovers, men who became public icons simply through wealth and influence. The play is set in the 1930s, which was really the dawn of that culture: not just film stars, but businessmen becoming celebrities in their own right. There’s something very deliberate about placing the story in a moment when money, power and aspiration were so tightly bound together, particularly in an American, capitalist context.

What’s interesting is that Gregor understands exactly how to construct that image, and why people are drawn to it. Watching him is almost like watching a slow-motion car crash, you know he’s behaving terribly, but you can’t quite look away because you want to understand how he’ll manoeuvre his way through it.

By the end, you see a real shift in the dynamic between him and Basil. Gregor even refers to Basil as his conscience, the part of himself he tried to push away years earlier. That tension is what makes their relationship so painful, Basil is still trying to reach him, while Gregor is holding him at arm’s length.

[CM]: The play is set in 1934, but its themes of power, succession and reputation feel strikingly contemporary, some people have even compared the tone to the TV show Succession.

It’s been said that the staging will have a modern feel in a similar way. With the current political climate in mind, do you think a more modern staging changes how audiences interpret the story, if at all?

[LK]: Yeah, absolutely. As you’ve read in the script, it’s that world of these big, moneyed families. I think the Succession comparison is that sense that they can just have anything. There’s that moment in Succession where the character Roman Roy says to a kid, “If you hit this again I’ll give you a million dollars,” and they can just do that, almost just to mess with someone.

So in the rehearsal room we had to remember that these big gestures, things that normal people in the 1930s wouldn’t even have dreamt of, were completely normal for them. When they talk about figures like “I’ve left you a million dollars,” that would now be the equivalent of twenty or twenty-five million in cash. It’s basically play-money to them.

There’s also the moment where we realise Gregor is wanted and up for arrest, and Basil comes in with the newspapers and drops them on the table, saying, “What do you think of that?” In the kind of Succession world of it all, that gesture almost feels like another big power move, but in reality that’s the point where everything becomes very real. He actually is being wanted by the FBI, and that’s genuinely frightening. So it’s about remembering that they are playing with fire, and that even though inside their bubble it can feel trivial, the consequences are huge.

They’ve lived in a world where they think they’re invincible and have no need or want because they have that much money. Basil is different. He’s living as a piano player on 26 dollars a week and has cut himself off from his father’s money, so he’s had to learn the practical realities of life very quickly.

[CM]: Frank Langella, who previously played Gregor, once said, “The darker I make him, the more the audience seems to like him,” almost in a Richard III sense. How have you approached workshopping the dynamic between Basil and Gregor with Ben Daniels?

[LK]: He’s been with the show for a couple of years now, since it was in its infancy and they were doing workshops, so he just knows it incredibly well. He’s extraordinary, and it was almost a bit daunting in those first couple of weeks coming in and working with him and thinking, “How am I going to match this?” because he has this incredible energy and really embodies the part. But very quickly we built a friendship and trust with each other, and that’s allowed us to push the relationship to those extremes, really fight and hate each other, and then also love each other and not want to say goodbye. So it’s been brilliant.

[CM]: Man and Boy mattered enormously to Rattigan as he saw it as his last chance to be taken seriously. Why do you think it matters now? And what do you hope audiences take from Basil specifically?

[LK]: Well, as you say, it deals with these big figures you hear about in the news, people we think we understand, or think we know what makes them tick, and the play maybe gets you slightly closer to how those kinds of people operate. But it’s also a family drama. It’s about not fitting within your own family, trying to move somewhere new and build a different life, and still being drawn back into that world.

It’s funny as well, it’s camp in places. It is Rattigan, after all. There are lines like “your girlish intuition has led you astray”, which are still there because we haven’t changed the script. Those very specific Rattigan-isms are enjoyable to play and, hopefully, enjoyable for an audience too. We’re just pushing them in a slightly different direction. And there’s probably no better place to try that than the National Theatre, which has that history of being quite radical, of working with interesting people and doing things differently, and having the resources to take those risks.

In terms of why it matters now, it speaks both to those larger power dynamics and to something much more personal, the feeling of trying to step outside the expectations you’ve been born into and realising how hard that actually is.

With Basil specifically, I think he has a really strong sense of integrity, but he’s also quite lost and fighting against something that may ultimately be a losing battle. If he were able to be more open and more honest with himself, things might be easier for him, but that’s exactly what he struggles to do.

[CM]: You moved from filming Leonard and Hungry Paul into theatre quite quickly, and the two projects sit in very different tonal worlds. How do you experience the shift between screen and stage, and what does each space allow you to do as an actor?

[LK]: The shift from TV to stage is quite different, but the short answer is that it’s a real joy, and a bit of a privilege, to get to do both.

They’re completely different processes. On a TV set there’s often very little rehearsal You might run the scene once to see where it sits on camera, then you shoot it forty times from ten different angles and move on.

Theatre is the opposite. You rehearse for weeks and then every night you go out knowing that whatever happens out there is something you’ve created together as a company, and there’s no one coming to save the day if something goes wrong. That’s what makes it dangerous and really exciting. The rush afterwards was extraordinary. There’s something about live performance that you just can’t replicate anywhere else.

People still want to come together, sit in a room, and share that collective in-breath before the same story unfolds. That’s been happening for thousands of years, and I don’t think that disappears, it might change, but the impulse is still there.

Terence Rattigan’s Man and Boy runs at the National Theatre, London’s Dorfman Theatre from 11 February to 14 March 2026.