“Is society a shit show?” Ahead of his second solo show at London’s Carl Kostyál gallery, Callum Eaton’s answer is simple: “Yes.”

A quick glance at What A Shit Show reveals the truth in this semi-ironic, semi-serious quip. Across the wood-clad walls of the Savile Row gallery, Eaton draws on the absurdity of the Dada movement and the low-meets-high sensibilities of Pop Art. In ‘Toxic’ (2025), a collaged cut-out painting, he depicts a kitchen cleaner with its handle and wilting flowers arranged into a modern-day bouquet — both beautiful and literally poisonous. In ‘You Got Burnt’ (2025), the texture of a charred piece of toast is rendered in neurotic detail, while a mid-scene car crash in ‘Hurt People Hurt People’ (2025) feels both true-to-life and utterly out-of-place.

This uncanny and, at times, unserious odyssey through everyday symbols, consumer products, and near-disasters gives way to a world where everything we know feels suddenly ridiculous. As Eaton tells me, he seeks to create a “space where reality can become slippery,” open to new interpretations in new contexts. Today, his probing at the boundary between order and absurdity feels particularly necessary – after all, are we not mere moments from our own car crashes?

To use ordinary symbols as statements on the contemporary is an approach familiar to Eaton. In fact, the Goldsmiths graduate is best known for paintings of life-size ATMs adorned with what we’ve come to expect from late-stage capitalism — think Coca Cola, Lloyd’s Bank, and even some ads for a “very sexy / busty / brunette”. Where the new exhibition extends this series is in the works’ shape. With a new cut-out approach, Eaton’s objects are literally decontextualised.

In the lead-up to What a Shit Show, Cold Magazine spoke with Eaton about irony, disaster, and what he learned during his recent residency in New York. Walking through topics as serious and unserious as one expects, Eaton is revealed to be startlingly sharp, concise and touch wry.

The COLD Magazine (CM): Why are we obsessed with car crashes, burnt toast and catastrophe?

Callum Eaton (CE): You’d need a psychologist for the official answer, but it’s about experiencing fear at a safe distance. It’s not too far off from watching a horror film – you can confront something disturbing without being directly involved. There’s something very human in that impulse.

CM: Is society a shit show?

CE: Yes.

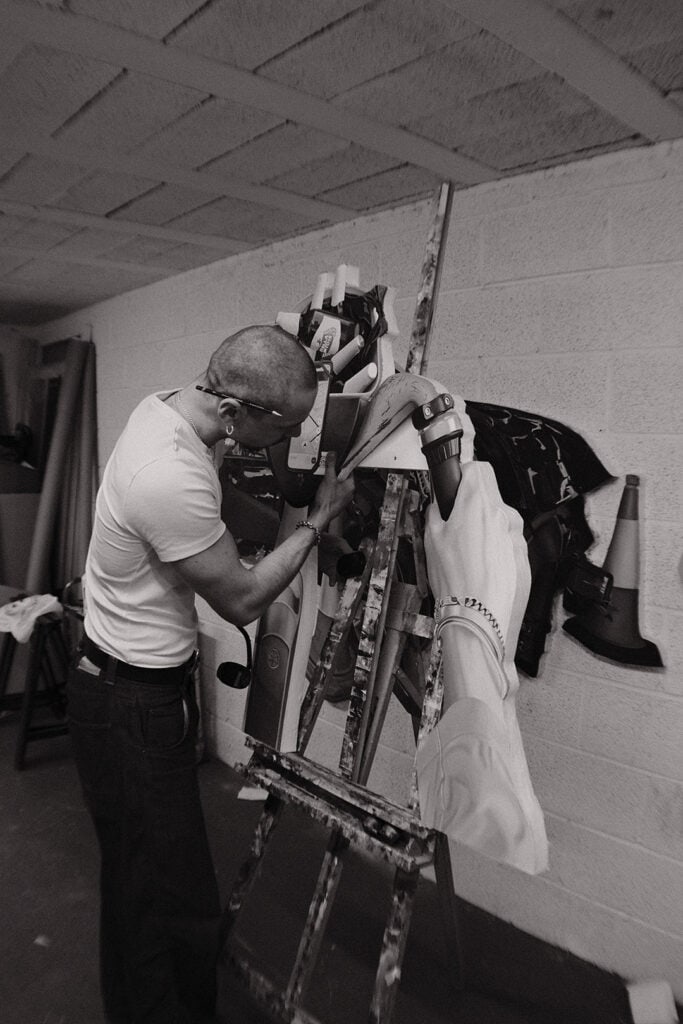

CM: Walk us through a day in the studio.

CE: I’m an early bird, which I inherited from my dad. I usually get to the studio around 8:30. The cycle there – also a hobby inherited from my dad – is where I mentally map out the day. A mandatory black coffee on arrival, previously paired with a cigarette – but I’ve quit – and then I dive straight into painting. I’m quite methodical. My works are layered. I’ll paint until around 6pm, then head to the gym, which I’m trying to substitute for the pub. It works… sometimes.

CM: You’ve described choosing subjects as like ‘picking out rings in a second-hand store’. Does that still feel true? What draws you to a subject now?

CE: I still photograph anything that catches my eye, often without logic or purpose. I have an instinctive urge to document it. Later, a red thread usually reveals itself. With What a Shit Show, my early subjects – a burnt piece of toast, a car crash – made no sense at the time. But I trusted my intuition. At this point the process feels more like being a sniffer dog. I follow the scent of whatever interests me.

CM: You’ve also just completed a residency at the Christine Mack Foundation in New York, a city defined by consumerism and chaos. How did it shape you?

CE: I loved it there. I seem to have a strange ability to stay calm in the eye of a storm. Except in Times Square, which is my hell on earth.

The constant movement and noise of big cities really inspire me – the sirens, the endless change, the detritus that accumulates. It’s a lifetime of subject matter. I’m also drawn to liminal spaces like a random street corner or a view from the train window. I often find those in-between places more interesting than the destination.

CM: Let’s move further into your work. As your pieces approach hyperrealism, they become a touch uncomfortable. How does the ‘uncanny valley’ – the discomfort when non-real things feel almost real – play into your practice?

CE: The realism in my paintings pushes them into a space where reality can become slippery. The ‘uncanny valley’ is that moment when recognisable things start to feel unfamiliar, when the everyday becomes eerie. I’m interested in that psychological wobble. You’re forced to confront reality. By rendering objects with that level of precision, I’m not trying to fool the viewer — I’m trying to get them to look again.

CM: How do irony and absurdism encourage critical reflection?

CE: Replicating everyday objects spotlights how absurd they really are. Humour is also a powerful disarmer. It creates an entry point, making the work more accessible.

CM: A few years ago, you were known for your ATMs, painting within their pre-determined rectangular structures. Now, you’re creating cut-outs. Why?

CE: Making the cut-out works changed everything. Before, I was confined to square and rectangular canvases. Surprisingly few objects naturally fit those shapes — architecture does, but everyday objects tend to be irregular, curved, or awkward. Cut-outs gave me the freedom to focus on more personal subjects.

CM: The exhibition features objects on the brink of disaster – a car crash, burnt toast, an empty fire extinguisher. What drives this focus on risk, suspense, and impending destruction?

CE: Usually, I have a rough vision for a show. This time I had none. I was simply drawn to these things. It’s been a challenging year personally, and the studio is where I process things indirectly. I always go through a breakup when I paint smashed or broken objects. I think painting without a predetermined outcome lets my emotions choose the subject for me. Even with this rationale, it does feel strange.

CM: In What a Shit Show, which piece stands out for how it caught your eye?

CE: ‘Hurt People Hurt People’ (2025), which depicts a car crash. On one of my cycles to the studio I took a wrong turn and ended up coming out of Hackney Marshes onto a different part of Lea Bridge Road. I saw a horrific car crash. I immediately started taking photos. I felt like Jake Gyllenhaal in Nightcrawler.

CM: Reframing everyday symbols as cultural artefacts recalls Andy Warhol’s blend of high and low. Do you see yourself among the Pop Art movement?

CE: They’re my contemporaries, even if they came before me. What I’m doing wouldn’t be possible without them taking those early leaps. I like to think I’m continuing the conversations they started.

CM: There have been many critiques of Pop Art-inflected works as unserious or of everyday subjects as low-brow. What is a ‘serious artist’? Are you one?

CE: I take what I do seriously, but at the end of the day, it’s just painting. I’m not curing cancer. Being an artist is a privilege; setting your own brief, working on what you want, when you want. That’s not normal. I’m grateful every day that it is.

CM: Do you feel tension between appealing to high-art collectors and maintaining your tongue-in-cheek sensibility?

CE: Honestly, no. I think people respond to work that feels genuine. I’m naturally a cheeky person, so that comes through in the paintings. I’m not trying to be tongue-in-cheek — I just am. As an artist you spend a lot of time on your own and embedding inside jokes into the paintings keeps it fun for me.

There is also a part of me that recognises the absurdity of being an artist and my work can sometimes shine a light on that. Making a painting of a crashed car that is worth the same if not more than a decent actual car. That’s mad!

CM: And finally, what’s your personal vision of a ‘shit-show’ day?CE: Funny enough, that was one of the original concepts for the show. I wanted a Joycean day-in-the-life narrative where everything goes wrong: spilling coffee on a laptop, getting a flat tyre, ending the night too drunk and texting an ex. That would be a truly spectacular shit-show.