Stepping into Crude Hints (Towards) at London’s No.9 Cork Street, the idea of an interior begins to unravel. Co-curated by artist Charlotte Edey and Ginny on Frederick’s own Freddie Powell, the exhibition turns rooms into sites of speculation – places where memory and material collide, where ordinary objects take on the weight of ritual. Across two tightly curated spaces, 33 works cluster in unexpected constellations: sculptures and artworks that question identity, multimedia works that fracture into archives, and surfaces that glow with both care and decay. It’s a show about the comforting and unsettling instability of the spaces we inhabit, interiors refusing to stay still, folding time and meaning into something perpetually unfinished.

The show’s title comes from John Soane’s speculative manuscript, Crude Hints towards a History of my House (1812). Here, his home becomes a future ruin, narrated by an antiquarian speculating on its origins. Rather than a straightforward record, Soane layers fiction and archaeology, describing the house as part Roman temple, part burial site, part magician’s lair. Soane is accompanied by a contemporary poetic text by Hannah Regel, Crude Hints Towards a History of My Flat, where she reflects on bringing her first child home and the shifting, mutable nature of inhabited space. This writing acts as a quiet counterpoint to the visual works.

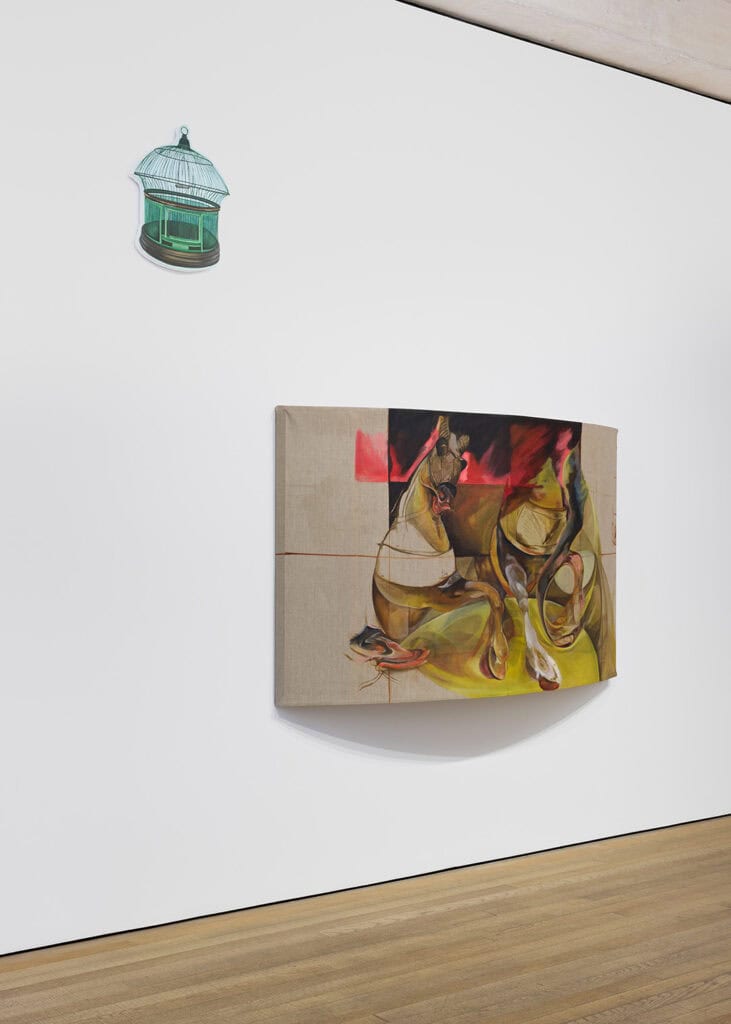

In the show itself, I found myself crossing through the boundaries of different spaces, my eyes moving across the works of 22 artists – each a fragment of an imagined interior, a nest of work, a different rhythm. Shigeo Otake’s The Crossroads of the Six Realms (2024) and The Pest (2025) pulse with surrealist energy and immersive worldbuilding. Otake’s adorably unsettling characters feel like emissaries from a parallel domestic universe, their presence both playful and uncanny. Elsewhere, Christina Kimeze’s diptych Caryatid I (2025) and Caryatid II (2025) push figuration to its limits. Her ghostly bodies hover within confined spaces, opened up to and closed in by a stark monochromatic palette – a meditation on a disorderly system and spatial tension. Edey herself contributes a single work, Axis Drift (2025). An exercise in symmetry, its pentacle-like structure hinting at ritual and orientation within an unstable interior.

The Cold Magazine spoke with curators Edey and Powell during the show. What follows is a conversation about origins, processes and layered logics behind Crude Hints (Towards).

The COLD Magazine (CM): What came first: the impulse to curate an exhibition together, or the discovery of Soane’s Crude Hints as a touchstone for the show?

Charlotte Edey (CE): I’ve been obsessed with the Soane Museum since I was a student, I’ve drawn there countless times. I came across Crude Hints towards a History of my House while researching for Thin Places, presented at Frieze London last year. Soane imagines his residence – Lincoln’s Inn Fields – as a ruin inspected by visitors in the future. Masquerading as an antiquarian, he analyses the “strange and mixed assemblage” of artefacts, fragments, documents, artworks, and curiosities, speculating about whether the self-reflective construction was originally a Roman temple, a burial site, a convent or a magician’s lair.

It’s such a strange, speculative text. Soane is inviting the reader to inhabit multiple, possible histories. It is a natural framework for an exhibition with multiple interpretations of the interior.

Freddie Powell (FP): Charlotte has been with the gallery since its foundation, and I have a terrible habit of leaving her studio with a book or article she’s pressed into my hands and then returning it very late, often months later. The impulse to organise something together was already there — we’d been circling around the idea for a while after Frieze London.

CM: How did your decisions develop moving from concept to artists to installation?

CE: I had been researching at the Jencks Archive and Drawing Matter in Holborn. We were interested in having artists approach a single subject from different vantage points. Aldo Rossi, John Hejduk, and Charles Jencks are all incredible theorists with a deeply poetic understanding of space and architecture as a receptacle for meaning and memory – it was these works that formed the early anchor for the rest of the show. In the spirit of Soane’s collecting, Hejduk’s Sentences on The House has been pinned on my wall for years – a Bachelardian reflection on space and living. I feel lucky to display two of Charles Jencks’ drawings in the show – they are for his Garden of Cosmic Speculation, a thirty-acre cosmological masterpiece. For the install, we aimed to echo the Soane collection: fragmentary, personal, maximalist. It’s this layering of objects that fascinates me.

FP: I wanted to avoid a clean, linear narrative. Soane’s house is full of unexpected sightlines and shifts in scale, so we tried to preserve some of that energy in the gallery. Certain works sit in clusters; others occupy an architectural pause or a threshold. It offers moments that feel dense and layered, followed by quieter spaces where a single work can resonate on its own terms.

CM: The artist list spans generations and geographies. What was the logic – or intuition – behind bringing these particular voices into dialogue?

FP: Placing contemporary artists alongside figures who shaped spatial thinking for decades is really energising. I was also excited to bring in artists who haven’t appeared in the wider gallery programme yet, and the larger space at No.9 Cork Street allowed that. The moment where Megan Marrin’s work hangs high above Okiki Akinfe’s monumental, curved canvas is magical, and including both Jordan Nassar and Machteld Rullens highlights their incredibly singular relationship to a material, with Jordan’s Palestinian embroidery and Machteld’s constructed cardboard — each holding memory in a very physical and architectural way.

CE: The building itself is inverted — a layered space most of the works in the show occupy. Christina Kimeze’s work utilises the caryatid pillar to explore systems of interpersonal and emotional support, while Sophie Giraux makes wax rubber casts of wallpaper to archive the interior, which deeply reminds me of Charlotte Perkins’s The Yellow Wallpaper (1892).

CM: The show inhabits a space between construction and repair, certainty and speculation. How do you imagine moving in the space, stepping into unstable interiors?

FP: I imagine visitors moving through the space almost like exploring a house that’s slightly out of sync with itself. The semi-domestic hang, with the salon tucked into the back, encourages moments of discovery: a work looming overhead, another tucked around a corner, or one like Julien Monnerie that demands you crouch or step closer.

CE: Soane’s house today feels almost completely frozen in time, with all his thoughts, collections, lists, and letters left just as they were in 1837. That sense of things being paused lets you really feel the idea of the interior as a kind of extended archive: a place where architecture, memory, and identity are all stored together. Crude Hints shifts with that same idea, exploring interiors as spaces on the edge of things, where time, memory, and the self all coexist.