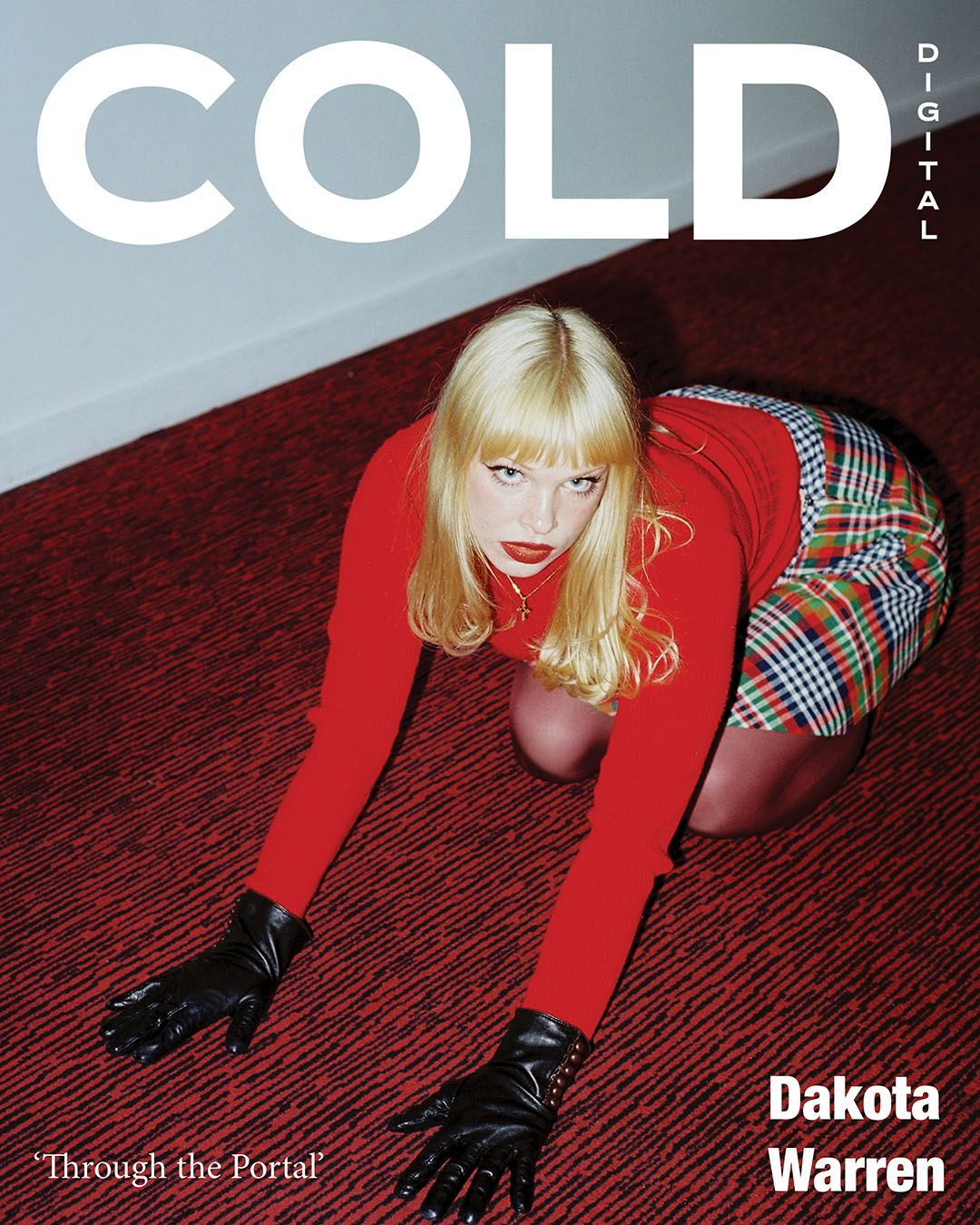

Through the Portal: A Conversation with Dakota Warren

Written by: Lexi Covalsen

Edited by: Lily-Rose Morris-Zumin

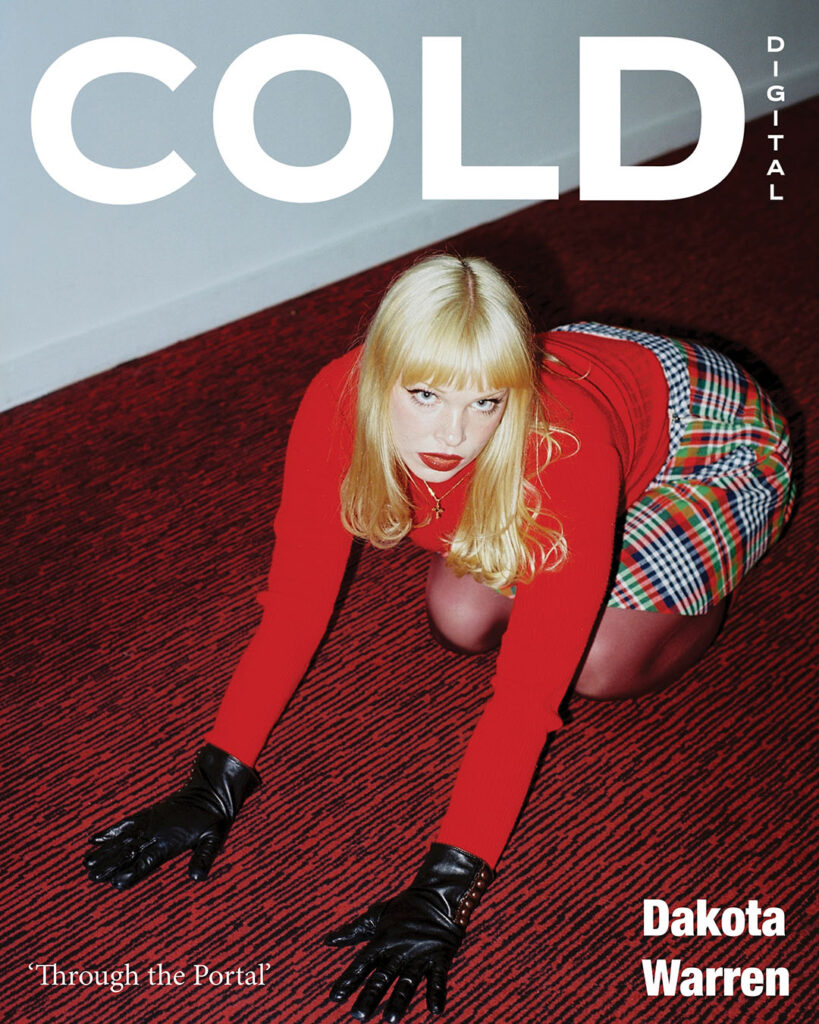

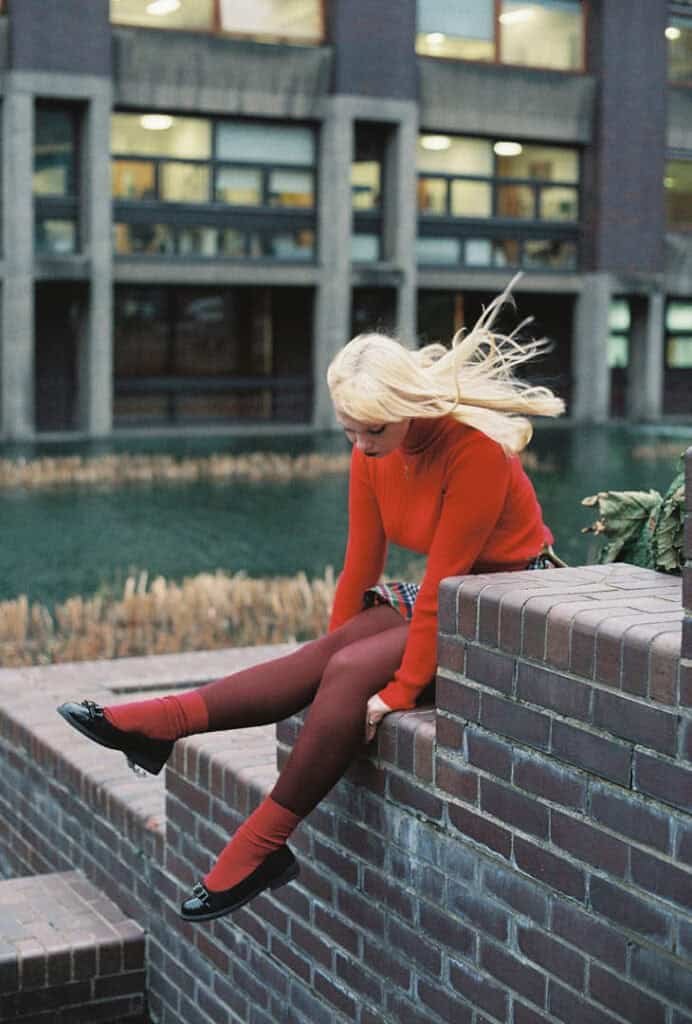

Photos by: Luvi Camera

When Dakota Warren first appears on my screen, the light from her laptop camera shifts and flickers, tracing her face as she laughs. “I just got a new MacBook,” she says. “It’s doing this weird face-tracking thing. Forgive me if I look distracted,” she laughs. Even through the pixelated lag of a midweek Zoom call, Dakota radiates a kind of 1960s wunderkind energy; white blond hair, sharp eyeliner, a soft sweater patterned like something out of The Twilight Zone. She seems half in this world, half already imagining the next.

I’m dialing in from a borrowed study room at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, door locked to keep out the chatter of school children and the squeaks of their trainers at bay. She’s in London. Outside, it’s one of those rare English afternoons when the sun decides to make an appearance, flickering through the turning leaves. And yet, England – both my home and Warren’s adopted one – plays only a walk-on role in our conversation. Warren’s thoughts are elsewhere, fixed on the dusty small towns of rural Australia. It’s there that her new novel, Be Happy I Am Mad, set for release in spring 2027, begins.

After launching onto the literary scene with her 2022 poetry collection, On Sun Swallowing, Warren quickly became an internet darling of the Dark Academia age. It’s easy to see why: her writing pulses with the immediacy and energy of online culture, yet it’s grounded in a carefully crafted, cinematic sensibility — contemporary womanhood filtered through the worlds of Donna Tartt. Every line feels deliberate, every image thoughtfully composed, reflecting a unique voice that’s as visually striking as it is intellectually compelling.

But Warren is on the cusp of something new. Three years since her first collection and two years since founding Nowhere Girl Collective, the online community she built for emerging writers and artists, she’s about to publish her second novel – a feverish, first-person coming-of-age tale. “It feels mad,” she admits. “I still pinch myself some mornings and get scared that I’ve made it up.”

The way she says it isn’t self-deprecating; it feels like confession. She talks about portals – a word she returns to again and again. There was the portal she walked through when she quit her job, left her country, and decided to become, as she calls it, “a capital-W writer.” There’s the portal she’s writing through now, shedding one world to enter another. “I’m big on environment and I’m big on intention,” she tells me. “I had to move out of the country and quit everything to even let myself think of being a writer. It had to be all or nothing.”

It’s tempting to romanticise that – all or nothing, leaving your dusty town for the big city, that sudden leap of faith—but for Warren, it’s not just an aesthetic. This is her real life, and it seems like a wild ride that she’s still trying to navigate. For this new book, she’s going back to where it all began.

“Australia,” she says, “has given me this kind of solitude and space and dust and stillness to grow as my own person, and I attribute my upbringing in Australia in this kind of this dusty, desolate place to who I am as a person and to my writing style and to the themes that I constantly repeat and find in my works, whether it’s poetry or fiction or essays or journal entries.”

Her poetry is full of that dryness – palpable heat. As she writes in one poem, “Yes, I can feel the burn too. I felt it my whole life.” Even now, thousands of miles away from home in London, she still writes from that place. “In order to let myself walk through the next portal and write about being a London girl or whatever…First, I need to pay my dues [to Australia]”

When she talks about her work, there’s a kind of sacred chaos to it. Nowhere Girl Collective, her sprawling online platform and creative community, began as “a place for people who didn’t know where else to put their art.” The name fits: a refuge for those in between places, ages, definitions, too tender or too weird for the usual literary gatekeepers. Each month, she posts an open prompt – twenty-four themes and counting – and writers from around the world submit poems, stories, and confessions. “I wanted to keep it messy and human,” she says. “It’s an anti-gatekeeping platform.” An invitation, she says, to other young women who feel like they might not have a seat at the IRL table of literary happenings. “Let’s all hang out together in this little online space,” is Warren’s battle cry.

And yet, when she describes the warehouse launch party – two hundred tickets gone in minutes, poems hung up on concrete walls, red wine and readings and noise – it sounds like a reincarnation of Warhol’s Factory, but for a new kind of generation: young, literary, internet-born, and allergic to pretension. “I just remember standing there looking around like, wow, this is actually quite quintessentially human and very necessary.” That night, she says, “people became friends for life.”

We talk about ambition, community, and the strange geography of artistic hopes. In Australia, she says, “it was just a big dream.” London, by contrast, feels like a conversation you can actually enter. I tell her I grew up in Georgia – small-town America, all Baptist churches and Trump campaign signs in yellow-green yards – and that I know that same hush of being “too much” in a place that asks for less. “We call it tall poppy syndrome,” she says. “When one poppy grows taller than the rest, everyone cuts it down. How dare it grow taller?”

We laugh, but there’s truth in it. The shame of wanting more. We sneer at ambition when it’s artistic, and not practical. “People who shame you for chasing your passion,” she says, “are often people who didn’t let themselves chase their own.”

Her voice softens when she talks about writing itself – the act, the labor, the shift from hobbyist to professional. She describes herself as “an absolutist,” someone who can’t half-do anything. For Warren, writing is about writing and not much else. “You can always tell when somebody is writing to be a Writer versus writing to write,” she says, “There is a massive difference.”

It’s not a visual project for Warren. As stylish as she might be, she didn’t get in the game to make it onto people’s Pinterest boards. “I feel like anytime I start talking about writing or literature, I get so cliché,” she laughs. “It really is so hard not to because—I mean, clichés exist for a reason, right? I feel like when the clichés come out, it’s just the passion seeping through.”

That passion finds its form in what she calls the “in-between space.” “I’ve always written in the in-between space,” she says. “I’ve always merged diary entries and poetry and confession and essays.” Her first publication, marketed as a poetry collection, is really one of these hybrid creatures. “It’s got poetry, but it’s also just got blatant journal entries slapped in there. And extracts from essays, cut up and pasted into these strange formats that resemble something like a poem.”

It’s a style that feels entirely her own – a kind of digital-age fragmentation that somehow reads as timeless. One wonders if the forthcoming novel – sapphic, gothic, and set within the dreamlike terrain of childhood and dirt roads – will inhabit a similar in-between space.

We circle toward queerness naturally, the way all the best conversations do, through laughter, confession, and a shared sense of recognition. When I ask if her novel was always going to be sapphic, she laughs. “There was never any other way,” she says. “It was always going to be this. Everyone always says that your first novel is the one where you have to get everything out – everything you’ve built up wanting to say up until that point. So I wanted to get out the rural setting, this sapphic story, the otherness, the queerness against the religious backdrop.”

“I just wanted to say all these things,” Warren says, emphatically, her hands moving and glitching on the laptop screen. The passion is, indeed, seeping out. “The first novel is just vomit. So let’s see how that goes,” she laughs.

That’s when we return to the idea of the portal. Like a fever breaking, this first book seems to have drawn out something – some toxin or shame that clung to her from the world she came from. The writing, she suggests, is less an act of invention than of purification: of being a certain kind of girl (a nowhere girl, perhaps?) and coming to peace with it. The result feels less like a debut than a transformation, a crossing over.

There’s a freedom, she says, in telling a story that isn’t autobiography but still hums with confession. “It’s safer that way,” she admits. “You can deal with things through the characters. You can say, ‘that wasn’t me – that was her.’ But of course, it’s always a little bit you.”

Her novel, like much of her writing, treats queerness not just as identity but as a mode of seeing. “People ask why it’s queer,” she says, “and I’m like, because everything about it is fluid. There’s an openness between genres and genders. It just is this constant, flowing, natural thing.”

The story, the structure, the emotions. It’s about being in motion. That same motion, she adds, defines love between women itself: the fine, dangerous line between devotion and obsession. With sapphic queerness, “you have this deep, uninhibited bond of friendship” which makes everything a bit more twisty. “Every queer thing I’ve ever had has been so perfectly intense and overbearing, it does kind of spiral into this madness” she says. “I don’t want to find the line between crush and obsession. I’m having fun in the in-between.”

Our conversation then veers into, of course, Sappho and vampires. It’s Sappho’s physicality that inspires Warren most. “Just the look of the female in itself,” she says, is described in such gorgeous terms that I would never think of. That was a big ring for me”

Next up is Carmilla by Sheridan Le Fanu, the “OG sapphic vampire gothic horror,” and Milk Fed by Melissa Broder. “That book made me feel a bit sick,” she says, “but that’s how I like to feel at the end of a book.” I tell her I agree – that art should sting a little. Often I find myself getting to the end of something and thinking, as one writer put it, “It was alright…but where’s the poison?”

Warren grins. “Exactly. You don’t want to feel comforted by literature.. Art is meant to disturb.” There’s something vampiric in the grin she gives the camera as she says this, and I feel even more excited to get my hands on her forthcoming novel.

When I ask Warren how she feels about being called a “confessional writer,” she doesn’t flinch. “I do confess a lot in my writing, but there’s security in the confession.” “If you put everything out there, the real secrets don’t have power anymore. You remove the shame.” She pauses, her tone suddenly serious. “We have such a shame culture, especially in our generation. Everyone’s obsessed with being clean and polished and perfect. I’d rather be messy and human.”

Later, she will email me a quote from the author Heather Havrilesky: “Being a confessional human being for me is like a defense mechanism. If I can tell you the flaw before you see the flaw, then maybe it’s okay.” I read it a few times and think about how rare it is to see someone own their vulnerability so openly. In a culture built on self-editing or strategic vulnerability, Warren’s approach feels truly radical. Hide nothing, gain everything.

That’s her rebellion, I think. No more “clean girls.” Just nowhere girls: writing through the mess, chasing portals instead of polish. Dakota laughs when I say that. “Exactly,” she says. “No more clean girl. More nowhere girl. Nowhere girl summer, we laugh, but when we look outside, it’s clear from the blue hour, British gloom that what we’re really stepping into is more of a nowhere girl autumn – and there couldn’t be anything more apt.

Our Zoom call warns that it’s about to end. “It feels fitting,” she says. “Portals, loops, circles – it all comes back around.” Her face flickers again in the light as she waves goodbye. I close my laptop and catch my reflection in the black screen – a girl from rural America who has just finished speaking with a girl from rural Australia about London parties and lesbian poetry and everything in between.

Writing has always been a kind of magic, but I’m not sure I’ve met anyone who understands that as intuitively as Warren does. She just keeps building portals – one sentence, one confession, one world at a time. And maybe that’s what the best art does: it doesn’t invent a world around you anew, but reminds you that the place you’re in – whatever town, or city, or stuffy room, is just one portal. You can jump out of it and into a new one any time you like.