For a poet, the first line is everything. And for Dan Whitlam that first line came when he was cut open, stabbed twice at 16 with a screwdriver.

Let it be known I told him I would resist leaning too hard into this part of his story (no doubt it’s well-chronicled) but it’s hard to want to start anywhere else.

In the nation that gave the world the Romantics – the bleeding, brilliant minds of Shelley, Byron, Coleridge – one must admit the idea of a new English generation’s poet finding his voice through such an act is compelling, to say the least.

That origin of Whitlam’s voice, discovered as a means of processing his physical trauma, pushes beyond backstory and begins to flirt with something greater. Mythos, we might say.

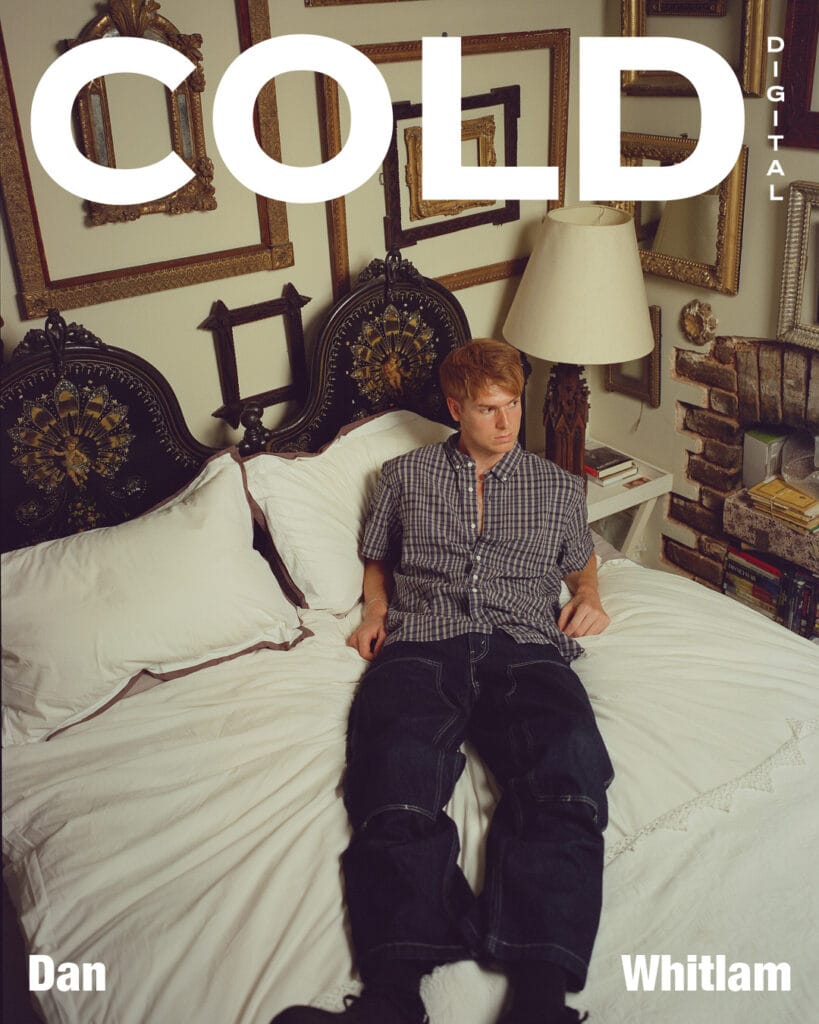

And the idea would be fitting. As I spoke with Whitlam, I couldn’t shake the sense I was speaking with an archetypical figure. Deep-voiced, dark-eyed, dressed simply and with a physique reminiscent of Renaissance sculpture, he seems made not only for this moment in time, but for any moment in time.

Far from a pound-store hipster trying to spin his angst into something cooly transgressive, Whitlam’s voice (especially on his stunning new EP, Mama Said) gravitates to themes much more classical: the passage of time, childhood nostalgia, grappling with generational change, the call of personal destiny and the bittersweetness of youth’s brevity.

Or more simply, as Dan put it to me, “love and loss”. We’re talking about thematic universality – which is rare today. Existing in a fractured zeitgeist, subset upon subset of emotional experience and perspective silo human souls into divided social groups.

When I listened to Whitlam’s music and poetry, I felt refreshed and called back to something more transcendent – something that bleeds through every barrier and speaks, first and foremost, to the most basic facts of one’s humanity: family, youth, love, memory.

Whitlam’s command of his craft is captivating, not simply how he’s able to employ the deep tenor of his voice to bring gravity to every line but for the lines themselves too, laid so effortlessly over each beat. He glides between genres, literary and hip-hop, poetry and music with infectious, natural rhythms.

Just five songs, Mama Says feels like a world in itself. It’s 15 minutes and 17 seconds of soulful reflection that had me time-travelling through my own past, my own youth – the glittering scenes it hurts so perfectly to remember. I imagine anyone who listens to this music will feel called to do the same, and that’s why it’s so important.

The future seems as tenuous as ever, the world’s days shaky with uncertainty and the people in it much more prone to personal distraction than personal reflection. So I don’t know if this world will give Dan Whitlam the attention he deserves in the coming years – though he deserves a lot.

But what I do know is that as modernity continues its dazzling 21st-century breakdown, we’re going to need a poet like this. An artist like this. A voice born in literal pain to rebind the various threads of human experience into a cable we can really hang onto.

We’re going to need someone to remind us: We’re here. We’re alive. That time moves no matter what we do – but that can never obscure the beauty (yeah, beauty) that once, for the briefest of moments, we were young.

I think that someone is Dan Whitlam. Here is our conversation conversation:

The Cold Magazine (CM): Dan, the EP is perfect. I’ve listened to it on repeat since I got to it – it’s stunning, really. I want to start, though, by asking: you introduce yourself as not simply a rapper but intentionally as a poet. Which of those identities is primary? Or are they coequal?

Dan Whitlam (DW): I’ve always found that for me the rap and poetry live in the same space. I’ve always testified to the idea that rap is just rhythm and poetry, so I try to keep it within that vein.

But the words always come first. In terms of my writing method, I write to a really simple beat or even a metronome sometimes – just the poetry, the words themselves.

It’s tough because people on social media like to box you in as one thing. If you’re a rapper or you’re a poet, you can’t really be both in some ways. I’ve found that difficult, bringing people over from Instagram and TikTok, where I found my fan base, to Spotify and stuff like that.

I’ve got a tour coming up and people are saying, ‘What is it? Are you doing poetry? Are you rapping?’ And I’m like, I’ve got a whole band behind me and a whole show going on. It’s difficult to translate it sometimes. But certainly, going forward, I want to be known as a rapper.

The poetry is where everything started. The words I write are quite poetic and I think that will always stay with me. So yeah, I’d like to say it’s rap, but there are definitely elements of poetry. I started in poetry, for sure.

CM: In your upcoming shows, are you planning at all to mix the two as you go through the set? I mean, will there be moments when you break – because you’ve got a book out – and will there be these little segues because you’re in such a genre-blending space? We love when somebody fuses two things we love and creates a new experience for us. Do you anticipate moments like that in the new shows?”

DW: Yeah, absolutely. Quite a few of my songs – I’ve got a song called ‘Juliet’ and a song called ‘Paper People’ – have a traditional rap form with the chorus, and at the end there’s a proper poem, like a spoken-word, freeform poem. The show lends itself to moments of poetry regardless if I play those songs.

I’ve also got moments where it drops down to just the keys—just my keys player and me. I tell anecdotes about growing up—my grandma being very prevalent in my life. She’d tell me her stories, I’d tell her mine—and this seeming anecdote naturally turns into poetry.

I like messing with the beginning of things. The audience will be like, ‘Oh my God, we’re in it—suddenly it’s rhyming.’ So it’ll definitely be a lot of music that’s on Spotify, but absolutely also new poems woven in.

But I think the tough thing with social media is that it’s amazing because you get to find a fan base and people who like your stuff, but also you need to minimise your craft and your work down to 40 seconds, which is always tough. Lola Young turning ‘Messy’ to a 40-second hit is incredible, but then you have to take that and you go to Spotify and listen to it for three and a half minutes.

So it’s a real chance to be able to tell these longer poems that three, four, five minutes long. So I’m excited to do that and have it kind of backed with my whole band, which would be really, really cool.

CM: Process-wise, you’ve got the album and you’ve got the book. Is there a point when you begin writing and think, ‘This needs to be on a page,’ and, ‘This needs to be on vinyl’? How do you navigate that headspace?

DW: It’s definitely difficult. Sometimes, if I’ve written something strictly for poetry and it really resonated with me or with other people, I’ll put it on the end of a song. It can help people know about the song if I put it online but it’s also a nice way to distill and cap off what I want to send across.

If I’m going to write something for a vinyl, for an album, I’ll write it with a metronome or a beat to a BPM. Then I’ll flesh it out and go into the studio with my producer and say, ‘I want to create a kind of Fred again beat – less heavy, very anthemic and really emotive.’

With the poetry I sit at my desk, one of my happy places. With music, I’m writing with a beat in mind and a certain BPM. That’s the main difference.

CM: When you’re free from the beat, does poetry bring a different kind of emotional relaxation?

DW: There’s definitely a huge amount of relaxation. Recently I’ve been writing poetry for the book and for online – my poetry online is what I’m known for – and I usually sit down knowing I want to condense something to 40–45 seconds. There’s a relaxed factor to it, but there’s also that thing in the back of your head – will this perform well?

As much as I try to create art just for myself, you can’t help but want things to go well. I definitely write with a lot of peace, but my happiest place is in my bedroom, writing at my desk.

CM: I’ve listened to the EP so many times… the nostalgia at the center—growing up and moving on, your parents in relation to you. When you were a kid having those experiences you talk about, was there a moment you realized you had a special relationship with words?

DW: As a kid, I lived in Russia – St. Petersburg – and in Istanbul, Turkey. I came back to London with my dad because my mom got ill and then passed away when I was nine. Nostalgia for me has always been imagining how things could have been different, creating alternative universes in my head.

Someone at a wedding recently said to me, “Oh, Dan, you were so bad with your words when you were a kid.” I think I had a bit of a speech impediment where I pronounced my W’s as L’s. It’s amazing to them that now I’m articulate. I had a lack of voice when I was younger. I was painfully shy and really physical. Sport and running, that was how I communicated with the world.

When I was 16, after getting stabbed in London, I wrote this poem about it. It returned to the boy who stabbed me and told his story. Being able to tell an account of something that happened in my life, in a way I could relate to the world and the world could relate to me, gave me an enormous sense of self-worth. I realised I can use my words to communicate my feelings and my story. I didn’t put down the pen.

CM: I read about your getting stabbed. I don’t want to belabour it, but it’s a huge part of your mythos. Did you feel you needed to process it somehow and the words presented themselves to do that?

DW: There have always been two things I found really difficult to write about: my stabbing, and my relationship with my mom. I felt anything I put down wouldn’t do it justice. But after the event I knew I needed to find something to make peace with it. I started writing about the event and it turned into poetry – it was rhyming.

I was heavily influenced by an American rapper called Joyner Lucas. He did this story about a boy called Ross Caprioni who got shot and then it resets and it’s the guy who shot him. I thought it was genius. I took real influence from that and put my own life and words into it.

CM: Poetry often takes a backseat to music in modern pop culture. Why still prioritise a book when you’re making such killer music? Does poetry itself still have a utility in the world?

DW: First of all, to have all my poems in a tangible thing, my book. I’ve had hundreds of poems collated alongside anecdotes and things about me. I thought it would be really cool to have something tangible.

Through the beauty of social media people asked, “Can I get this in a book?” I was presented the opportunity by a publisher called Bonia and I jumped at it. It’s been a dream of mine since I was 16, 17.

I knew it might confuse people – “Are you a rapper? Are you a poet?” – but the tying factor is my voice and my poetry, whether it’s got a beat or not. Now that the album’s coming out, music is what I’ll fully focus on. The book was a North Star, a bucket list, and the right time.

CM: Are you enjoying the ride – the shows coming up – and does the performance element energise you?

DW: My work on stage started with acting when I was a kid and I still do it now in pieces. I feel the most self-worth when I’m on stage – it’s my safe place. I love the buzz beforehand, being so nervous I don’t want to do it, and then as soon as I’m on there, I feel real peace and self-worth.

There’s something great about taking the words I wrote at my desk and having people sing back the lyrics I wrote at that desk. It’s a magical feeling. I’m enjoying the ride. The bigger something gets, the more pressure there is. I care a lot about what people think – I’m a bit of a people-pleaser – and with positivity online, you get a lot of negativity as well. I won’t pretend that doesn’t hurt, but it’s learning to roll with that and tackle it as it gets bigger.

CM: There’s this melancholy reflectiveness in the music – time passing, a bit of pain – but also confidence and optimism moving through it. Is that intentional, or does it just come from who you are?

DW: I’m forever an optimist. I’ve always seen the world as half full rather than half empty. I want to see the best in people and the best in myself. Everyone’s got their own troubles – it’s how you deal with it. We’ve got one shot, and I want to be an optimist and have a good time while we’re here.

CM: What actually puts you in the zone: meditation, ritual, or motion?DW: Doing something that takes your mind off forcing yourself to write is the best way. If I’m walking around and writing at the same time, or cycling and listening to a beat, I’m often pulling over to write. I write on the move a lot. As far as meditation, I haven’t really found it. I need a bit of chaos in order to write. The words come out of chaos rather than peace. I write a lot more when I’m going through a breakup or love – something quite extreme on the spectrum – and I do that best when I’m moving.

CM: You talk about voice, a person finding theirs. What do you hope your work gives people?DW: If there’s someone who’s shy or feels they don’t have a voice, I hope I can give them a voice or let them be heard—and let them know they’re not alone. I write about things that are relatable because everyone deserves to be heard. I’ve recently started therapy – I think it’s an amazing thing to do – and your voice is the one thing we own in this world. If I can help people have confidence behind theirs, that’s a great thing.