In 2013, a 17-minute video titled Dirty Girls was uploaded to YouTube by Michael Lucid. In it, a high-school-aged Lucid interviews his peers about a group of girls who embraced a riot grrrl ethos, making feminist zines and appearing purposefully disheveled. They were mockingly known around school as the “dirty girls”. Within its first day online, the video drew thousands of views – and the numbers steadily climbed. Not so long thereafter, this school project from 1996 – later edited into a short film for a 2000 festival run – became a veritable online sensation.

By 2025, this number has since jumped to 5.5 million views, a testament to the strange, lingering power of those few minutes of shaky, high-school-era footage. Its afterlife has stretched well beyond the internet too: excerpts are currently being shown at the Barbican’s season Dirty Looks: Desire and Decay in Fashion, running until 25 January.

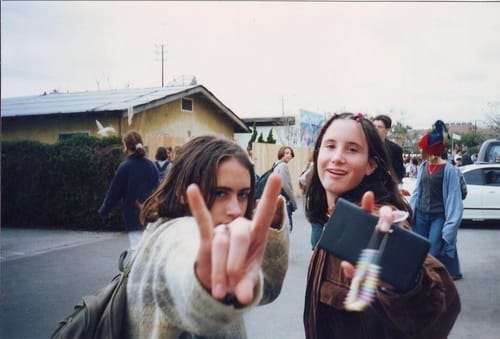

As the documentary opens, Lucid sets the mood with Batmobile by Liz Phair – an apt choice, with lyrics like “I gave it my best shot, I gave you the performance of a lifetime.” We meet 13-year-old Amber, one of the group’s two self-styled ringleaders, before a sharp cut to a couple of classmates in 90s-era outfits, sneering: “They don’t shower. They’re trying to be rebels…” It’s a clearcut case of bullying and othering on the one hand, and of nascent counter-culture instincts on the other. If the content is so straight-forward, what made it go viral in the first place?

Meeting with Lucid all these years later over Zoom, he tells me about the entire process of making the film, editing it, and uploading it. Years after its limited festival run in 2000, a film curator reached out, asking if he could post Dirty Girls to YouTube, having seen the name listed in an old catalogue and wanting to check it out. “Within a week,” Lucid tells me, “it had gone viral, it was incredible. And I will say, Tumblr helped.” I don’t expect him to mention Tumblr, but as soon as he does, it all clicks into place: 2013 Tumblr would’ve loved the dirty girls. “I was savvy enough to know: Tumblr is really big. It was 2013, you know,” he continues.

Later, I looked up a list of 2013 pop-culture events, to better remind myself of what it was like to be online back then. I came across this list from Buzzfeed, which itself feels the perfect website to capture early-2010s spirit.I’ll take you along with me: number five: “Miley Cyrus twerked on stage (at the VMAs) and some people were not having it”; number six: “Everyone was obsessed with playing Flappy Bird”; number 59: “What Does the Fox Say? was the most viral video on YouTube.” Meanwhile, Tumblr was booming as a social platform, fresh off its $1.1 billion acquisition by Yahoo. This was the reigning era of the Tumblr girl – if you were around back then, you already know just how easily Dirty Girls slots straight in.

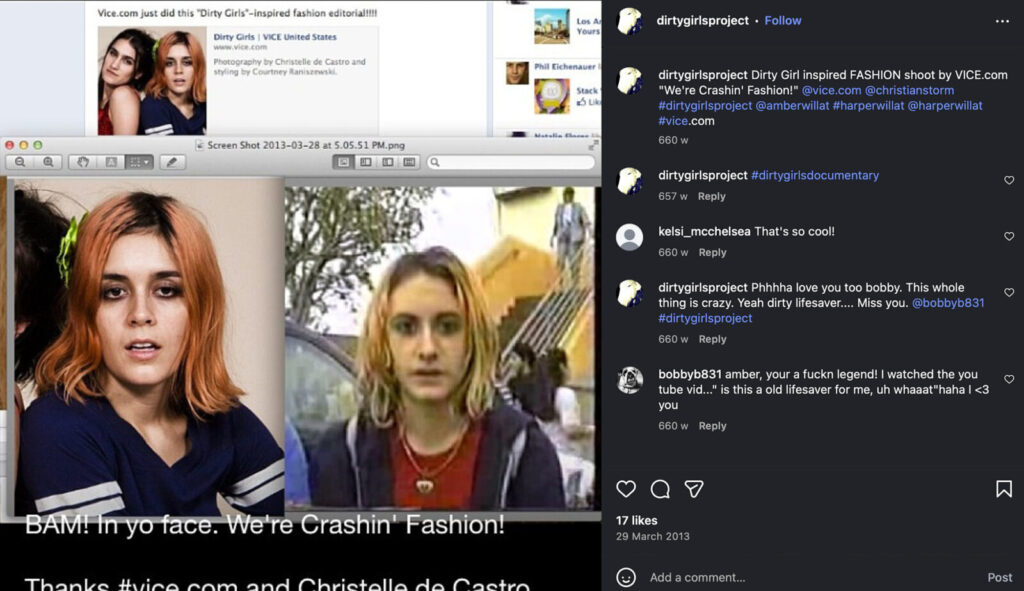

In my research, I also excavated this Tumblr post from user @whereareyouarienette, titled DIRTY GIRLS: A Feminist Analysis, which outlines why the documentary was so popular at the time. Amongst other reasons, the poster writes: “In many cases, people love this video because it’s like a time capsule of the 90’s that came out of nowhere.” Lucid and I had spoken of this too, talking about the fashion as well as the VHS grain of the film itself. “That 90s video aesthetic totally became a part of it,” he tells me, “I love seeing how it’s become a time capsule of the 90s.” Back in the Tumblr post, @whereareyouarienette writes that: “by the end of the film, many people just want to be friends with them. Vice.com found them so cool that they created a Dirty Girls-inspired photoshoot.” It’s hard to find this editorial online now, but many of the pictures are reposted on Tumblr – with a few having made it to Instagram too.

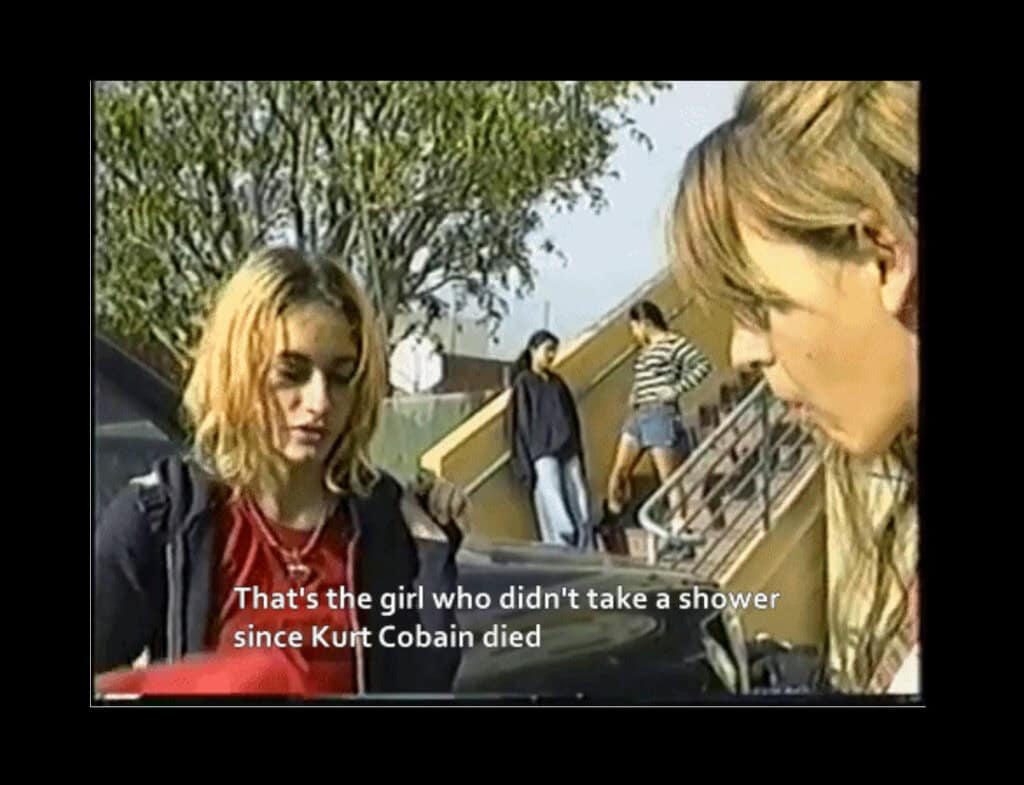

So what was so cool about Amber, Harper and their dirty-girl friends? According to their (often older) peers, they were desperate for attention, as if they didn’t know what they were doing to themselves. One student tells the camera: “It’s just unacceptable, they look like trash, they’re wearing garbage… I just don’t understand why that’s something they strive for. I mean, what does that say about you? You’re filthy, you’re filthy!” She looks visibly shaken, as if the appearance of the dirty girls is a personal affront. Another student repeats this sentiment, just in different words: “I find it personally offensive that they’re fighting for women, because I’m a woman and… (laughing) they’re not.”

Lucid tells me that the extremity of this public reaction to the girls was a source of inspiration for filming them: “Everyone was aware of them and gossiping about them. It really was this phenomenon on campus, people were fascinated by these very young girls – they were only 12 and 13 – and they were so precocious, doing what almost felt like a provocative performance-art stunt. The rumor was that they never bathed, that they were always pulling some kind of antic on campus, engaging in all sorts of ‘outrageous’ behavior. I was fascinated. Even then, I was already really interested in pop culture and in provocative public figures, from Courtney Love to Madonna, people whose so-called outrageous behavior actually had a lot of intention behind it. I was very aware of that sensibility, so I immediately became a fan, an admirer.”

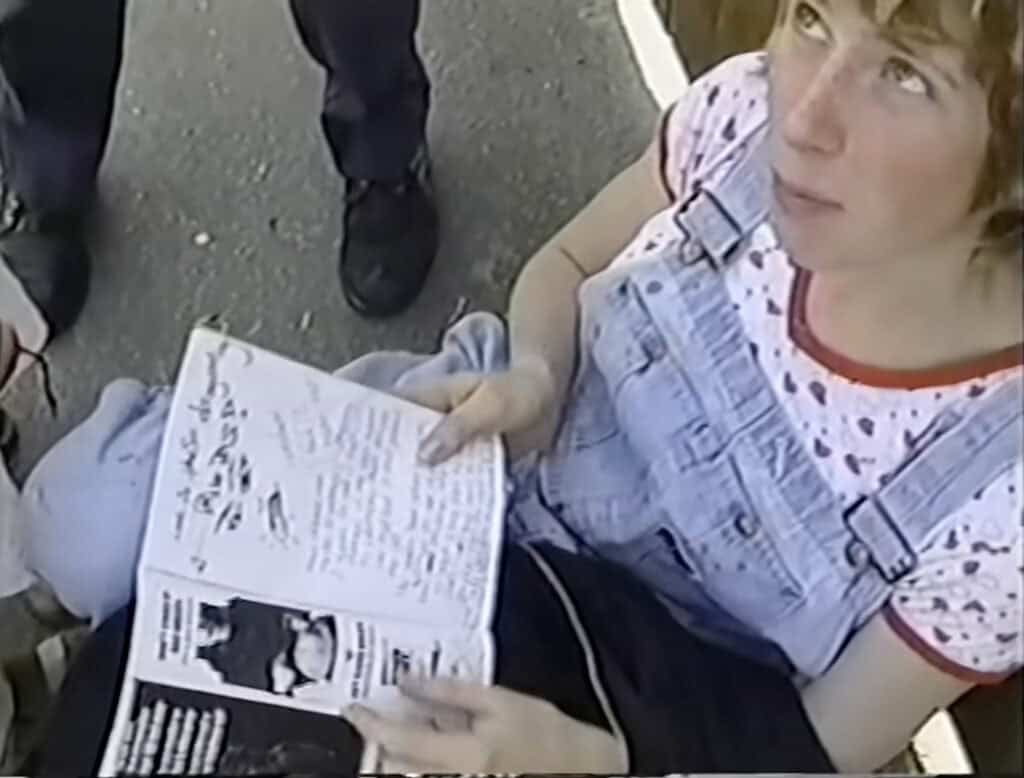

And when the camera finally turns to the girls themselves, they have no shortage of things to say. They’re unmistakably young, but fiercely passionate, fully aware of how they’re perceived. Responding to the idea that their feminist zines were naïve or misguided, Amber says, “That is just the meanest thing to say, that we don’t know what we’re talking about.” When the film was first completed, Lucid tells me, an hour-long cut was screened at the high school, and many of the same teens who had mocked them ended up apologizing.

Back in 2013, @whereareyouarienette wrote, “Our culture has changed drastically since the 1990s. There are many more spaces for feminism now than there was at the time this video was shot. Many of the things the girls were ostracized for in the film are now, in many circles, considered cool.” I find myself wondering how true that is to 2025. On one hand, feminist ideals are broadly familiar, even casually assumed, by huge swaths of teenage girls. On the other, we’re knee deep in trad-wife aesthetics and anti-woke microcultures blooming across the same feeds. I look at the dirty girls, whose rebellion was so tangible, so insistently visual – “that’s the girl who hasn’t taken a shower since Kurt Cobain died!” – and I wonder whether girls today would have the resolve to make themselves explicitly, socially unappealing.

For a generation that has grown up with phones in hand, endlessly scrolling Instagram and everything adjacent, is self-curation just too baked in? I ask Lucid what he thinks: “Maybe social media, and the ubiquity of smartphones and selfies, has made people so much more self-aware of their image and how they appear online. Back then, there was a kind of naivete. Even in the 90s, video cameras were around, but people weren’t as used to being on camera, so there was less self-consciousness. I think that ties into how there’s less of an underground now. Maybe I’m wrong, but it feels like any counterculture is immediately online, immediately on social media, and it never gets the chance to exist off the grid.”

Looking back, it’s clear that Dirty Girls endures not just because it charts the evolution of teenage feminism or the shifting ways girls perform (and refuse to perform) femininity, but because it strangely captures so many other fault lines at once. It’s about how social groups harden in high school, how girls talk about themselves and each other, suddenly the question of class is discussed, and how parents shape the kids who then shape the culture around them. It’s astonishing how much unfolds in just 17 minutes – so much so that it feels quite miraculous that a high schooler managed to catch it on tape at all. Lucid tells me he had no idea what he was walking into: “I wasn’t aware at all before filming it… it was all new to me. And I did have the awareness even at the time of, like – whoa.”