A 20-something records herself with the phone’s front-facing camera tilted at a 45 degree angle. To the rhythm of Skeeter Davis’ 1962 hit It’s The End of the World she performs a pantomime of thoughtfulness – lips pouted, brows furrowed, head cocked. Overlaid text reads: “Why is the earth kinda serving human race extinction right now”.

This video has 1.7M likes on TikTok, and over 9,000 comments of users expressing anxiety about the future. They are not alone. In a 2021 survey of 16-25 year olds across 10 nations, 75% of respondents said that “the future is frightening” and over half agreed that “humanity is doomed.” Between climate change, financial uncertainty and civil unrest young people are collectively asking themselves if this is the end. But the end of what, exactly?

‘Hypernormalisation’ is a term coined by Alexei Yurchak to describe the cognitive dissonance of living in the USSR during the start of its dissolution in the 1970s and 1980s. Despite cracks appearing in the political and economic system, politicians and citizens maintained the pretense of a functioning society – according to Yurchak, because nobody could imagine any alternative. This term was popularized by Adam Curtis in his 2016 documentary of the same name which posits that the West is living in a similar contradiction: we are taught to believe that the economic system that grew out of the post-war United States will remain fit for purpose forever and that history is a linear progression of continuous improvement. At the same time, we can see that this is a fallacy. What were once thought to be achievable markers of success like a steady 9 to 5, home ownership, and financial stability are now far-away dreams for more and more people – with simply having your energy bills paid for you enough of a fantasy to be offered as a competition prize.

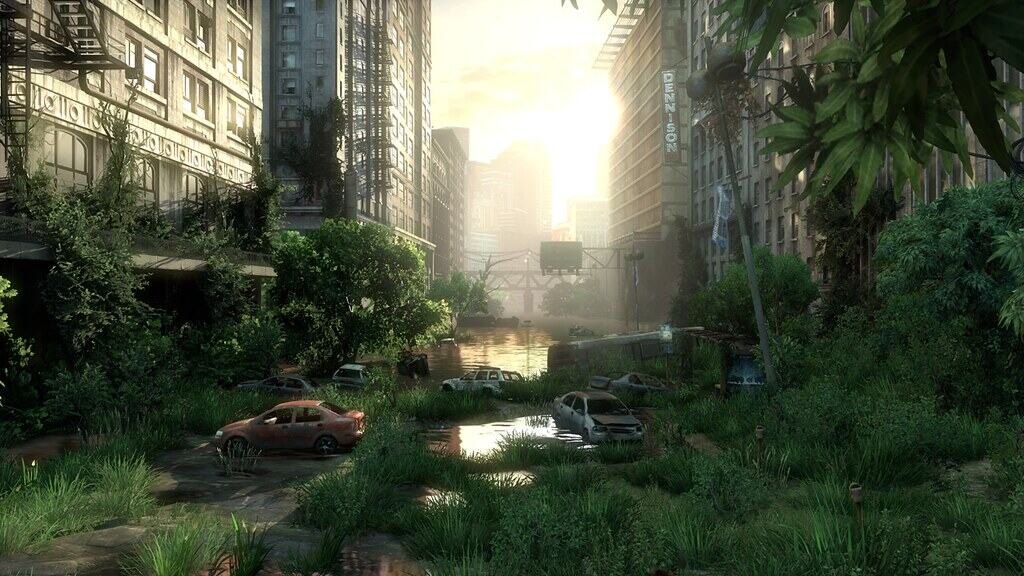

Meanwhile, our appetite for tales about the end of the world has never been higher. The hotly anticipated adaptation of the smash-hit 2015 video game franchise The Last of Us peaked on HBO in 2023 with an average of 30 million viewers per episode, the channel’s most-watched debut season ever. A Quiet Place grossed $341 million at its opening week in 2018, with its sequels A Quiet Place Part II and A Quiet Place: Day One in 2024 continuing to achieve commercial and critical success. Even stand-alone titles can prove successful: Sam Esmail’s 2023 parable Leave The World Behind remains the fifth most popular film in English of all time on Netflix, with 143.4 million views.

The popularity of apocalypse narratives, again, is not new. Humans love to imagine the end of the world – or more accurately, they love to imagine the time after the end of the world. The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest surviving literary texts at around 4,000 years old, references the story of a flood unleashed by the Gods to wipe out humanity with only a single ordained family surviving. This archetype of a post-flood hero appears again in the Hebrew Genesis, in the Hindu Setapatha Brahmana and the Zoroastrian Mazdais – all tales where a man (and sometimes a few others) chosen by the Gods survives the deluge in a boat he builds himself and builds society anew. The flood myth, then, is not a tale of destruction but of reconstruction and it echoes in our modern visions of apocalypse. Even controversial climate change satire Don’t Look Up ends with a sole survivor.

It may be because our history has been marked by consistent, successive periods of instability and unrest. We have come to see stability as the default when it is the exception. So to process this inevitability we imagine the end of the world where ‘world’ is a metonym distinct from ‘planet’, a cognitive framework indicating everything that we understand. It’s the end of the world as we know it.

Examining this hit by REM is a helpful reminder of earlier generations’ similar convictions that these are the end times. It’s The End Of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine) was released in 1987, two years before the fall of the Berlin Wall and subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union. Aside from its more overt Cold War era anxieties about nuclear apocalypse, it is also an anthemic acknowledgement of the possibilities inherent to destruction. If you pay attention to the lyric sung over the titular line in the chorus, the survivor narrative returns: ‘It’s time I got some time alone.’ Even in the portrait of annihilation that the song paints is the assumption that the speaker survives, relieved from the pressures of modern life, ready to start anew.

Because annihilation is besides the point – what we are looking for is salvation. We reach for post-apocalyptic narratives in times of uncertainty not because we actually want the human race to be wiped out, not because we crave suffering, but because we want to imagine what we might do with the freedom to start again. For all the hardship and terror inherent in these stories there is a perverse comfort – that the end is not the end, but a hard reset.