Choreographer and dancer Florentina Holzinger returned to Paris after shocking French audiences in 2023 with performances of TANZ (2019), a punk-feminist ballet where dancers strung up by meathooks pirouetted ten-feet above ground. This time, the Grande Halle de la Villette hosted Ophelia’s Got Talent (2022), an aquatic spectacle based on the symbolic figure of Ophelia – drowned heroine of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, incarnated as a translucent beauty in a bath of flowers by Millais.

In keeping with the deconstructive aesthetic of TANZ’s representation of the dark side of classical ballet, and SANCTA (2024)’s reimagining of the Catholic Church as a sexually liberated queer-feminist utopia, Ophelia’s Got Talent reckons with the myth of Ophelia – archetype of the pure and innocent, sacrificial female victim whose fate serves as a metaphor for patriarchal violence.

There’s a classical side to the performance with its harps and harpies. Pale nymph bodies dive in and out of shimmering waters to the music of Schiller’s 1797 ballad The Diver. Holzinger calls out literary figures such as Rimbaud and his La blanche Ophélie who ‘floats like a great lily,’ a white ghost in her long veils.

Hinted in the title, the production is also a spoof of the popular Got Talent reality TV franchise conceived by the infamous Simon Cowell – perhaps a deliberate gesture to the structural parallels between reality TV and performance art. As Claire Bishop highlights, both partake in similar rituals of exhibition, exploitation and humiliation of their subjects. Collapsing traditional boundaries between spectacle and reality, audience and spectator, both create hybrid participatory spaces where authenticity is at once prescribed and undermined.

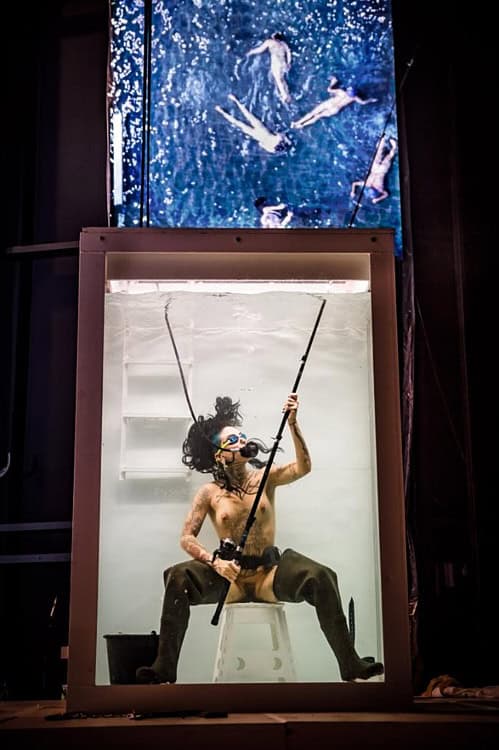

The performance opened with a long-haired, drunken and moustachioed Captain Hook, our host for the evening, trouser-less with full pussy out. She descends the stairs behind the audience in the fashion of a cheesy showbiz entertainer. Things progress like a typical talent show, except everyone is naked and unhinged. The first act is a woman from Chesterfield who tells the story of a deep-sea diver trapped underwater through aerial pole dance. Next is a sword-eater, Fibi Eyewalker, who claims to contain a piece of the ocean and deepthroats a camera to reveal slimy fish swimming in her entrails to prove it. A judge tells her she wanted to like the act, but her stomach said no. As a Brit who witnessed the peak of Britain’s Got Talent (BGT)’s cultural significance in the late 2000s and early 2010s, I was one of the only people amongst tight-lipped Parisians to laugh out loud as the next judge dropped the classic line: “I didn’t like it. (Drawn-out pause) I LOVED IT!”.

Holzinger has received high praise within the art world for her ability to communicate ideas and references that seamlessly oscillate between high and low registers – arguably today’s most sought-after cultural currency. In what is likely Ophelia’s Got Talent’s most memorable scene, five naked women suspended from the ceiling grind on a helicopter to the sound of thumping techno beats until it (the helicopter) cums all over the stage and crashes down into the neon swimming pool. Tongue-in-cheek integration of pop culture and camp comedy accompany the striking images, death-defying stunts, sex, nudity, blood, guts and bodily violence for which her performances are best known.

Humour and irony, (which serve not only to entertain but also disarm the viewer) have come to define Holzinger’s unique poetics of subversion. These operate through seamless movement between moments of levity and gravity, tranquillity and violence, harmony and dissonance, and pleasure and pain. It’s what gives her practise a playful, witty and self-aware edge, notably setting it apart from the familiar abjection and endurance-based body art of the 60s and 70s, as well as from her Austrian counterparts, the Viennese Actionists – both often referenced in discussions of her work.

The talent portion breaks down after a tense Houdini-esque escape act carried out in a water tank goes wrong, leaving the audience wondering what’s real and what’s not. Before long a crew of bottomless butch sailors storm the stage and break into maritime folk dance, complete with grand jetés that serve vagina to the back row. Eventually the scene dissolves into a dreamlike meditation on the mythology that binds women and water. The focus turns centre stage to the swimming pool, its gently lapping waters all the more seductive against the backdrop of an unairconditioned auditorium during a heatwave.

Perched high on her chair, a lifeguard spins parables of the sea as swimmers glide below with effortless grace until, in a flash, they metamorphose into fish. Thrashing and writhing to escape lines being cast by fisherwomen, one is eventually caught and hangs from the ceiling like a limp trout – a sacrificial victim like Ophelia.

It’s near the end of the performance that a decidedly emancipatory message runs clear: what if we free Ophelia from patriarchal fishhooks and reimagine her as a symbol of resistance? In Holzinger’s typical style, we arrive post-confrontation with the violent extremes of female experience. Here this involves discussion of rape, abortion, and her own childhood eating disorder – the story of a 10-year-old girl who fills herself up with water instead of food. In a bid to deliver justice, Captain Hook recruits a row of kids from the audience, because what greater symbol of hope and new beginnings is there than a child? They (the children) hold up Mirrors of Venus to humanity and the blood-dimmed tide is loosened. The swimming pool runs red, women transform into Charybdis-like sea monsters, and the sky rains down a torrent of plastic water bottles as an infernal storm of judgment unleashes itself onto the stage.

Closing with a final talent act – a tiny girl with a crystalline voice who sings a song of hope for the future, followed by a dance routine set to the music of Ed Sheeran – the show could have ended on an uplifting note. But Holzinger and her cast remain onstage after taking their bows and announce that the Ophelia’s Got Talent we had just watched was a version heavily censored by French authorities. The artist had also shared this information via Instagram story earlier that day, one post featuring her ensemble in the nude juxtaposed with the “nude” sculpted bodies of a SKIMS shapewear ad – a comment on the censorship’s primary targeting of nudity in the show.

Holzinger goes on to explain that the French authorities objected to the children in the cast witnessing indecent exposure, justifying their ruling on the grounds of protecting minors. Bear in mind, however, that these children have already seen the show multiple times (94, to be exact, following its tour across several European countries) and are trained professionals, with their involvement regulated by Germany’s established safeguarding protocols for youth participation in the arts. Such a structure has yet to be established in France, a country known for its inadequate protection of young, marginalised actors and industry professionals.

The most absurd part, Holzinger reveals, was the additional reasoning given by the French authorities: “the French don’t see a difference between the naked body, especially the naked female body, and sex,” and “the naked female body belongs to the private sphere, only to the partner or to porn, and there is no need for women to be naked otherwise.”

This framing of the female body as inherently sexual is a central and enabling narrative of rape culture. It’s exactly what Holzinger tries to deconstruct through conscious expression of nudity in her work, which attempts to normalise the naked body and reframe it as something which is not immediately sexual or provocative. This is a concept that has driven feminist body art since the 60s. It was notably in Paris during Jean-Jacques Lebel’s 1964 Festival de la Libre Expression that Carolee Schneemann first performed Meat Joy, an ecstatic rite where bodies collide with raw meat to illustrate the materiality of flesh. Plainly revealing their ignorance of France’s avant-garde legacy, French authorities further justified their censorship of nudity by advancing the lofty claim that, in France, “the spirit is valued over the body” (whatever that means). Holzinger underscores the irony of this statement with a PowerPoint highlighting some key images from the French canon: Marianne, symbol of the Republic, bare-breasted; Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe; and Courbet’s world-famous vulva.

Holzinger has often discussed the way her rise in public visibility has coincided with the rise of authoritarian government and censorship, and the challenges this has presented. While the artist is no stranger to backlash and controversy, she informs us this is her first encounter with censorship on this scale. It’s also the first time Ophelia’s Got Talent has been censored. And it’s a decision that only strengthens the case for the work’s necessity.

Ultimately, Holzinger attributes it all to a lack of open discourse surrounding gender, sexuality and women’s bodies in France, where such topics are often avoided. Censoring art that attempts to envision an alternative reality exposes how adhering to taboo perpetuates a culture of silence. Public scepticism about art’s ability to effect change is at an all-time high, and censorship threatens to turn that scepticism into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Yet, paradoxically, the French authorities’ response to Ophelia’s Got Talent serves as a tacit acknowledgement of art’s enduring power to provoke and disrupt. Believing themselves to be the judges of Ophelia’s Got Talent, they are in fact performers, actively participating in and magnifying the very spectacle they seek to control.