Standing “somewhere between the arthouse cinema and Iranian popular cinema of the pre-revolutionary period,” as its host puts it, Masterpieces of the Iranian New Wave (Cinema-ye Motafavet) returns to the Barbican Centre for a second season, running from 4 to 27 February 2026. The programme offers a rare showcase of restored films, many unseen since before the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Supported by the Iranian Heritage Foundation, it is organised by filmmaker, critic, and curator Ehsan Khoshbakht, reflecting his ongoing effort to recover these cinematic treasures and bring them to one of London’s leading cultural hubs.

Moving through relationships, romance, sexuality and oppression, I had the privilege of watching the first five titles, and was absorbed by them all. None shied away from discomfort. Instead, there was a striking frankness in the way they confronted ordinary, earthly failings and triumphs. And in the rainy start to 2026, few things felt more appealing than back-to-back trips to the cinema.

More than that, though, was sitting alongside audiences full of Iranians in the aftermath of one of the largest anti-government and bloodiest protests the country has seen in recent years. Introducing the festival’s second instalment, curator and host Ehsan Khoshbakht drew a stark contrast with the first, telling the audience that this time he stood before them “with a deep sense of shame and self-loathing.” Like many in the room, he said he had recently watched “thousands of innocent, young, beautiful Iranians being massacred,” and found himself asking, “is showing film the most important thing to do? Is it important at all?”

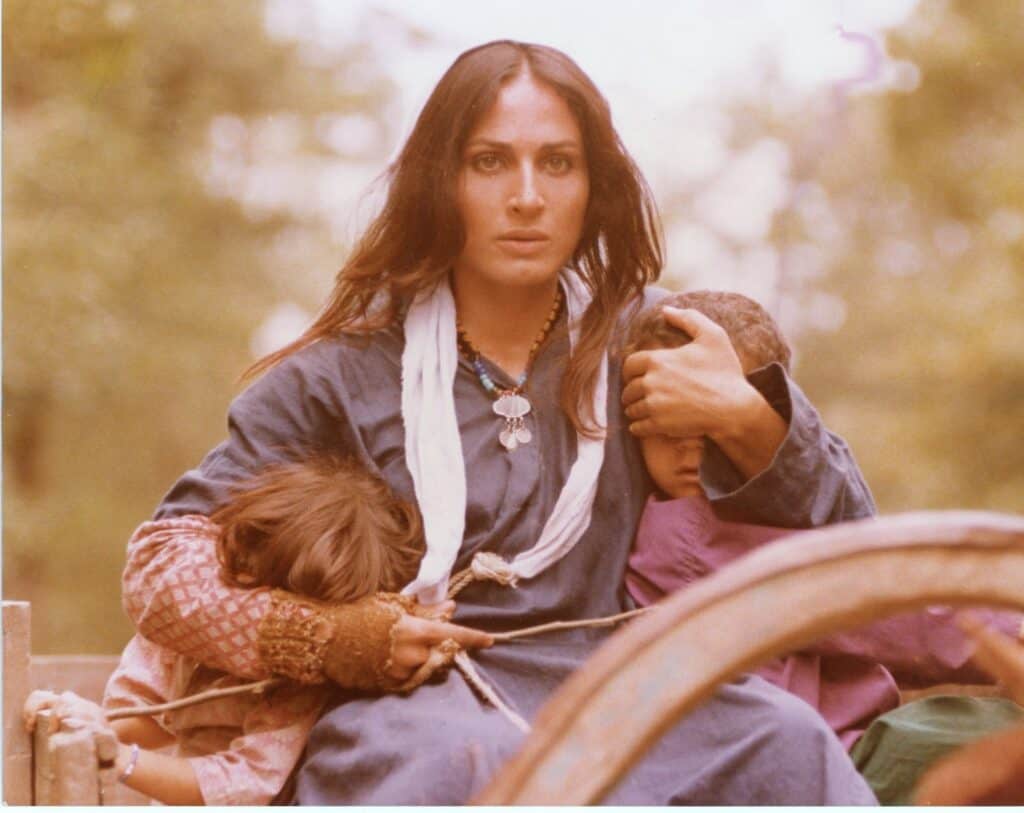

The Ballad of Tara (Cherike-ye Tara), 1979, dir Bahram Beyzaie

His answer, however, was resolute: “the mere fact that the current [repressive] regime in our country doesn’t want the majority of these films, the films in the programme, to be seen, is good enough for me to show these films at every opportunity.” Many, he noted, “were made against odds, when they were not supposed to be made, finished,” or, as with the case of The Ballad of Tara (1979), once completed were not allowed to be screened publicly. “If making films was and is an act of defiance,” Khoshbakht concluded, “then showing films shares a similar meaning as making and producing them.”

The Ballad of Tara, by the late Bahram Beyzaie, was the first film on the programme. The director passed away this past December, and I, like many Iranians, had been revisiting his work recently in memory of his mastery. Completed in the year of the Islamic Revolution, the film was never shown in Iran. It blends iterations of femininity, folklore and motifs from classical Persian literature to evoke a modern samurai epic. In his introduction, Khoshbakht emphasised how Berzayie “uses the concept of the Shia passion play by offering both a secular and a feminist interpretation of it.”

Tara (Susan Taslimi) is thrust into grief, intrigue and the haunting legacy of her father’s sword. Her performance is commanding, incredibly attuned to the more mystical currents of the programme, and lends the film an unsettling and dreamlike haze.

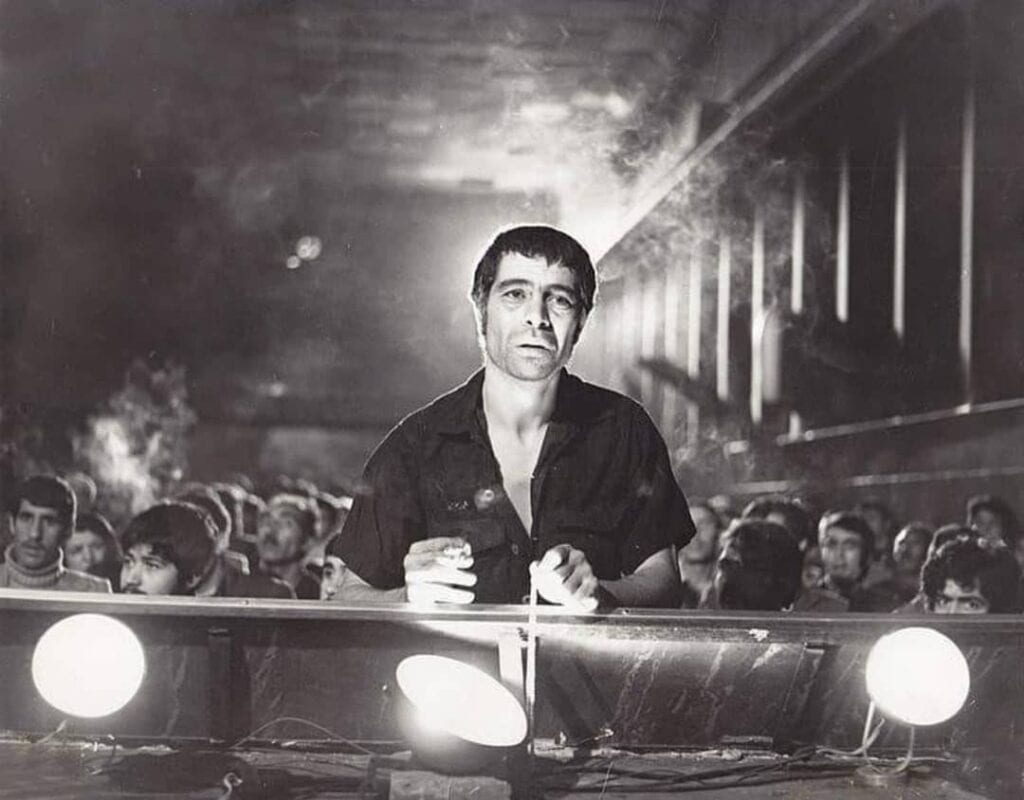

The Postman (Postchi), 1972, dir Dariush Mehrjui

The next day, a full house returned to watch Dariush Mehrjui’s The Postman (1972), shown in the UK for the first time via Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project. Based on Georg Büchner’s unfinished play Woyzeck (1836-37), the play follows a poor soldier exploited by those above him, exploring poverty, mental collapse and social injustice.

Mehrjui places the laconic Taghi, a meek and complacent postman, at the centre. As with other films in the season, it incorporates a deep sense of interiority within a busy plot. We watch Taghi move through his world while hearing the monologues that betray the slow accumulation of resentment beneath the surface. His descent into madness intensifies a sense of humiliation and inadequacy as he notices his wife’s wandering eye, blurring the lines between what is lived and what is imagined.

What makes the film so unsettling is not simply the violence of Taghi’s unraveling, but the banality of its origins. He is confronted with the indignities of class, masculinity, and social power that were characteristic of Iran at the time, and continue to be. These themes run throughout the season, but they come most sharply into focus in The Postman, an intimate yet political portrait of interior collapse that reveals how self-doubt and internalised oppression can either corrupt us or become something we learn to resist.

Journey (Safar), 1972, dir Bahram Beyzaie

Next up were Journey (Bahram Beyzaie, 1972) and A Wedding Suit (Abbas Kiarostami, 1976), a complementary pair. Beyzaie’s film inherits a child’s-eye perspective on the badlands of Tehran’s margins, while Kiarostami shifts towards the city centre, using a small predicament to build palpable tension. Presented together, they showcase how the Iranian New Wave used stories stemming from childhood and adolescence to convey wider societal burdens, using the lens of innocence to navigate typically adult anxieties.

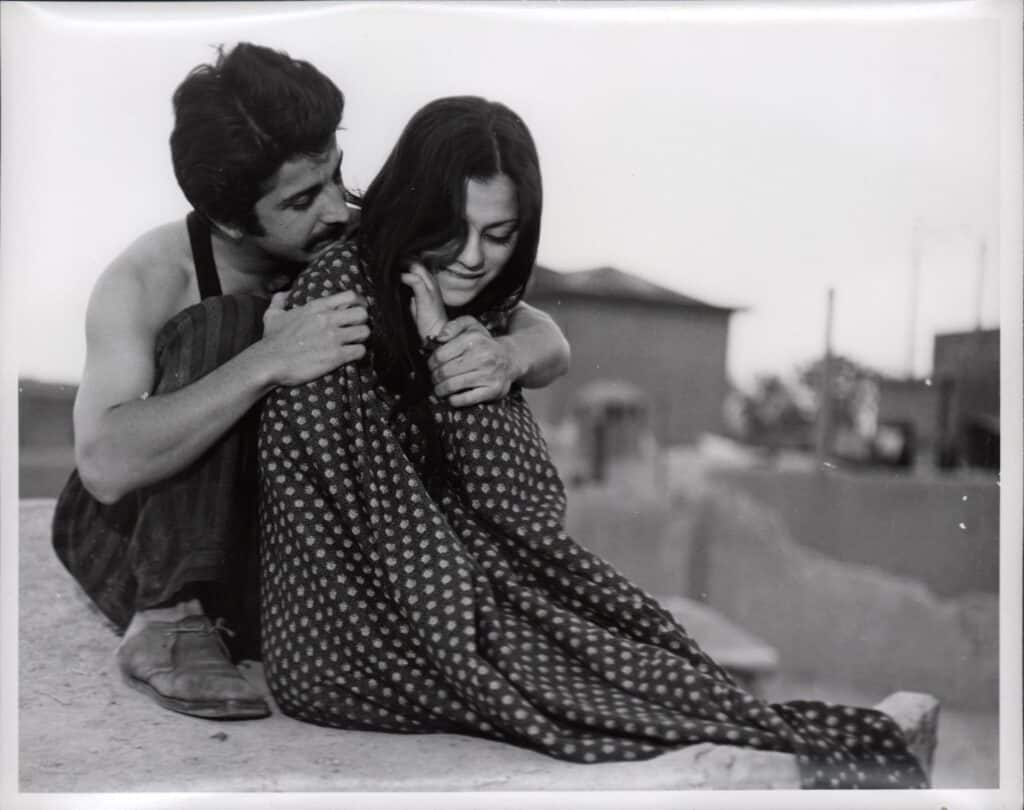

The Deer (Masoud Kimiai, 1974), a cult classic of 1970s Iranian cinema, follows a fallen champion and heroin addict who, upon reuniting with a leftist former classmate, achieves a final, luminous moment of revolutionary redemption. The true impact of this story was made by the brilliant Behrouz Vosoughi, a megastar of the era, whose every gesture, expression, and line conveys the fatigue and determination of a man reawakened after years of withering.

The Deer (Gavaznha), 1974, dir Masoud Kimiai

A standout of the week, without question, was Nosrat Karimi’s The Carriage Driver (1971). Introducing the film, Khoshbakht joked that the “Iranian notion of a comedy is one that starts in a graveyard and ends in disaster.” I don’t think I have ever been in a cinema where the entire audience laughed for the full runtime, nor have I found myself still giggling about a film hours after it ended.

In this playful comedy, young lovers Morteza and Pouri face an uncomfortable obstacle. They can marry only if Morteza first agrees to a union between his widowed mother and Pouri’s father, the carriage driver, played by Karimi himself. The film is often described as a meeting point between Italian neorealismo rosa and Iranian filmfarsi.

The humour of this film is rooted in the sheer force of the carriage driver’s personality, but it also carries a sharper irony: religion and tradition are selectively invoked, twisted and conveniently discarded whenever they stand in his way. This is where its neorealismo rosa quality comes through most clearly, the romance and domestic qualities are established on the surface, yet anchored in social critique, as well as quotidian negotiations of authority and power. The satire of it all feels especially pointed in the context of Iranian society historically shaped by autocratic rule, where piety and pragmatism share a precarious coexistence.

The Carriage Driver (Doroshkechi), 1971, dir Nosrat Karimi

Coming back to film as a form of resistance, Khoshbakht made a valid point. One of the first major events to symbolise a changing tide in Iran as the Islamic Republic rose to power, was an Islamic fundamentalist attack on a cinema. On the evening of August 19, 1978, over 400 people were killed in the burning of Cinema Rex in Abadan, symbolising the perceived threat of a place where ideas could be shared and, subsequently, run free. It was a stifling of artistry and liberty in Iran, one of many acts that would lead to the current state of aggressive censorship in the country now.

But artists remain defiant, treating cinema as yet another playing field against the system. Masterpieces of the Iranian New Wave is a reminder of film’s unfaltering power to provoke and bear witness. The continued relevance of these works across decades, moments of political upheaval, and generations is a testament to the enduring resonance of their ideas. They also showcase the extraordinary talent behind them, from actors and directors to producers, many of whom risked, and continue to risk, censorship, exile, or even death for the sake of their art.

Looking ahead, audiences can look forward to some repeat showings, as well as documentaries, more political satire, romance, and crime. This includes Secrets of the Jinn Valley Treasure by the iconic Ebrahim Golestan, sure to bring an excitement and familiarity with its “Monty Python-esque” presence.

The festival continues to invite Londoners to celebrate Iranian people and culture, offering not just entertainment, but a chance to engage with Iranian history, society, and imagination in a way that is otherwise obscured by the news cycle.

The event takes place until 26 February 2026. Tickets for upcoming films can be found here.