That’s the thing: Hamza Ashraf didn’t do anything. The filmmaker, photographer and writer has been exiled from his birth country for one reason and one reason only — for living as an out gay man.

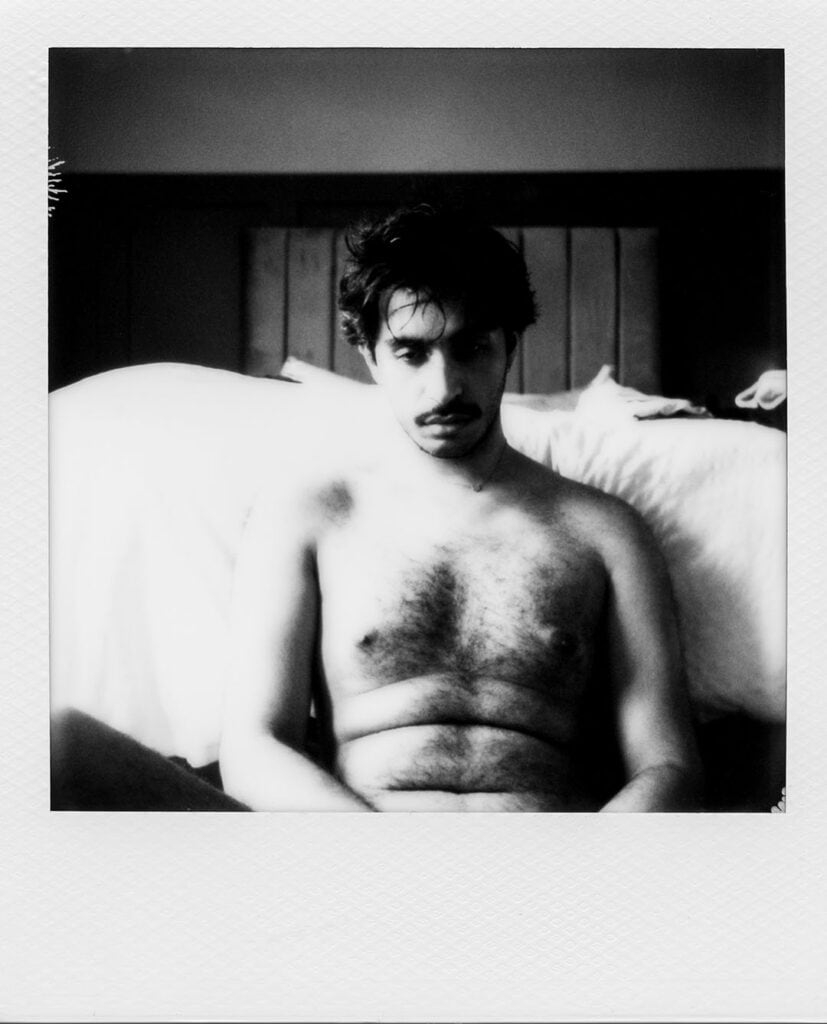

When we first log onto Zoom, he’s sitting by the window of his flat in Leeds, morning sun falling across his shoulder. Around his neck, there’s a small gold pendant necklace, ricocheting the light. There’s a kind of composure to him, but also the restless current of someone who’s still building a home in real time. It looks like there might even be an unopened box in the right corner of the screen. Is he coming or going?

“I think I can coexist,” he says early on, “these two versions of me.” He doesn’t elaborate on what these two different versions might be, but he doesn’t have to. Like many other people whose lives have been bulldozed by any number of things from natural disasters to miscarriages, divorces, deaths, there will always be a before and an after. For Ashraf, the bulldozer came in the shape of a red stamp on his official documents: banned for 5 years from his home country in the Middle East. Today, there’s the one it happened to, and the one who survived it.

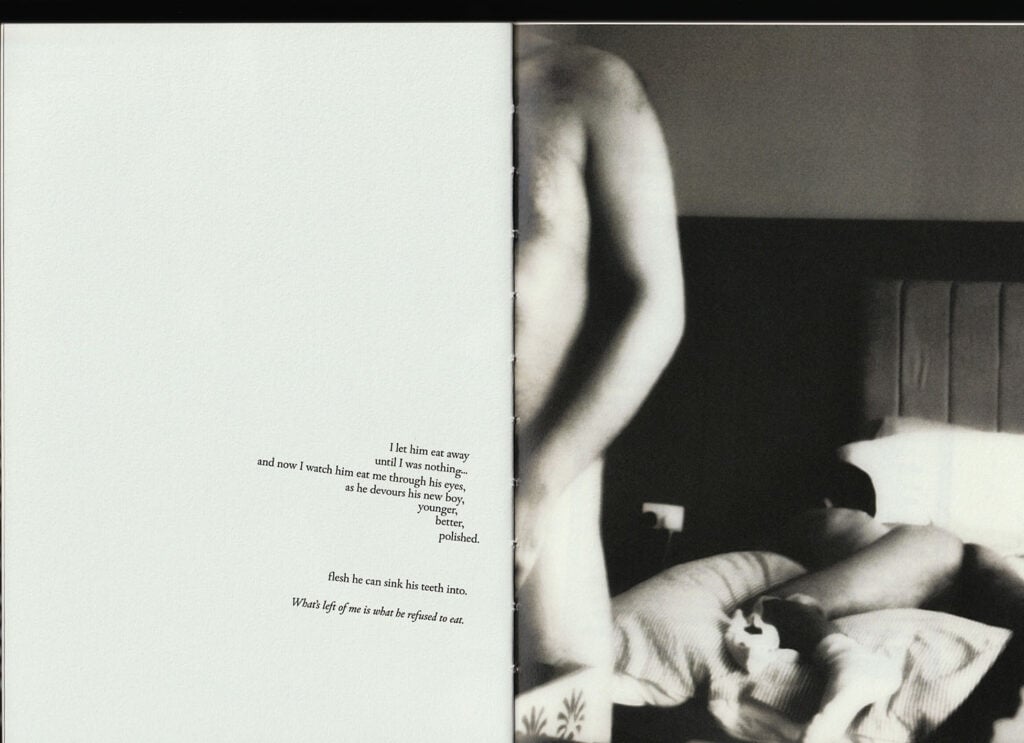

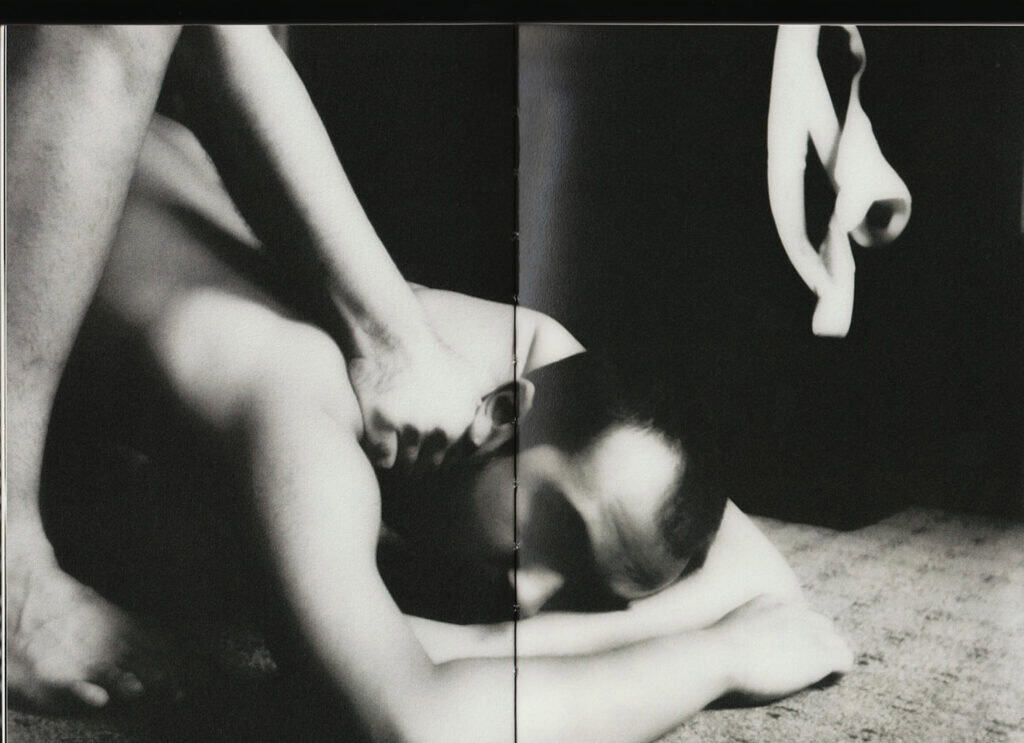

Ashraf’s newest collection, We Fear No God, But Ourselves, feels less written than unearthed. A hybrid work that fuses memoir, poetry, and photography, it blasts sunlight into the darker corners of shame, desire, fetishisation, and exile. In tracing the aftermath of being outed as a queer Muslim man, Ashraf does more than just narrate his life. His openness is shocking; it’s almost as if he’s handing the reader the same blade he’s used on himself, daring them to cut just as deep.

A torrent of image and memory, it documents what it means to lose your country and, in doing so, to confront your own doubleness. His work refuses chronology, looping and circling instead, like thought, like obsession.

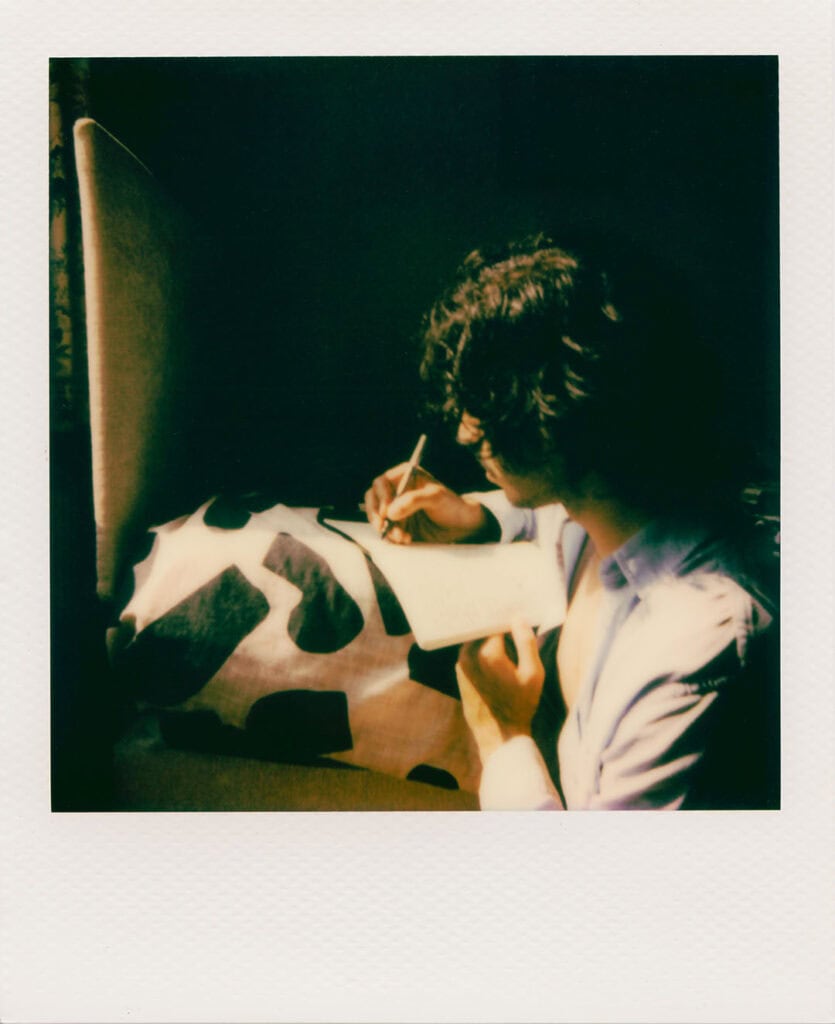

He tells me the book came out of what he calls “the initial shock” of being banned from his home country. It is a direct product of what he calls “the flood […] hopelessness and statelessness […] the emotions that came when the ban happened.” The line between confession and craft are blurred, and even now, Ashraf sits firmly in that confessional mode: “if I write something,” he says, “I am going to put it out.”

I tell him that what strikes me about We Fear No God, But Ourselves, is how the book feels less like a catharsis and more like an ongoing conversation with pain. Traditional therapy, I say, can sometimes feel linear, squashed into a process of purging, healing, and moving on, as if recovery were a clean sequence of one, two, three. But Ashraf’s work resists that structure. It’s as if he’s taken a literary approach to therapy, one that loops and circles back, where there is no real beginning or end. We return, always, to the same wound, seeing it differently each time.

I tell him it reminds me that trauma isn’t something we outgrow; it’s something that changes shape with us. You could be seventy and suddenly feel compelled to write about something that happened when you were seven.

On this topic, Ashraf reveals that he is currently working on a follow-up to We Fear No God, But Ourselves. This one, he explains, is slower, more deliberate. The hurricane has touched land, and now, in his forthcoming book, Ashraf is getting started on the clean-up process. “How do I ground myself in the idea that I have to stay here?” he wonders. It’s a question still hanging in the air.

In conversation, Ashraf’s tone drifts between ease and intensity, with flickers of bashfulness. He’s careful, almost protective, when it comes to the specifics of his exile — the whos, the wheres, the whys. But, in a sense, he doesn’t need to explain. We Fear No God, But Ourselves has already done the revealing for him: if not the biographical facts, then the emotional ones.

The book holds darkness, yes, but also self-awareness and flashes of sly humour. When I ask him to unpack the distinction between “ban” and “exile,” a tone of exasperation leaks into his voice. “Ban,” he says carefully, “is what the authorities write on paper. When you say ban, people are like, ‘what did you do?’ And it’s like, ‘I didn’t do anything.’”

It’s a word that is bureaucratic, clipped, impersonal. Exile, on the other hand, is the feeling. The emotional truth of what happens when your home becomes a place you cannot return to, even though it is embedded in every part of who you are.

Exile, in Ashraf’s usage, is layered and expansive. It is tied to the bodily experience of memory, the emotional geography of a life uprooted. “Even though the ban is a five year ban, ‘exile’ encapsulates this emotion that I keep trying to forget […] I can never still be my full self.”

He speaks of the ban with a quiet, measured precision, and he describes its weight as something that shapes his every choice: “I can’t just one day decide, yeah, I’m going to fuck off to Paris.” The remark lands with a half-smile, but beneath it is the reality of passport privilege — how these slim paper booklets, e-visa codes, and national numbers dictate not only the geography of our lives, but their psychology too.

“It’s a never ending cycle. There’s such a heavy restriction,” he says, “that comes with my identity.” As if gayness and Islamicness might appear side by side on a poster in an airport under the heading “Dangerous materials.”

That all-encompassing power of the passport seems, to me, to explain the stateless form of Ashraf’s work. In his art, the bureaucratic becomes personal; the image becomes language, and language, image. There are no borders here, maybe so in life, but not at least within the pages of his book.

It’s this tension — between the personal, the political, and the corporeal — that runs like a live wire through Ashraf’s work. His photography, composed of intimate portraits, linger on subjects caught between shadow and light, anonymity and exposure, longing and fulfilment. His poetry and prose, by contrast, give everything away. In We Fear No God, But Ourselves, pages from his actual diary appear, faithfully reproduced and left bare for the reader. Some entries are scratched out in dark, scanned-in ink blotches; others remain intact, painfully unguarded.

“I just didn’t know if I wanted to show those,” Ashraf laughs, “but I think as time went by and I kept looking at the pages I thought […] I can let that burden go. I think the last diary that’s left in there, it’s not crossed out at all.”

For Ashraf, text, image and moving image are simply different dialects of the same language. Each one is another attempt to articulate what it means to live in a body, and in an identity, so often policed by forces outside of one’s control.

And yet, there’s a confessional honesty in Ashraf’s work that resonates beyond the queer or diasporic experience. It is a model of vulnerability that refuses neat catharsis. Trauma is neither linear nor finite, and neither is exile. They shape the rhythms of daily life, the possibilities of intimacy, the politics of mobility. Yet, he emphasizes that exile does not erase creativity or joy.

Leeds, where he has resettled, has grown into a place of belonging. “Leeds is so multicultural and I’ve been very, very fortunate to have made friends from similar backgrounds as me and who identify the same way as me. I’ve made my own little family here.” While Ashraf’s story traces the familiar, often tragic arcs of queer life — exile, alienation, shame — it also hums with a quieter, persistent note of queer joy.

His friends, partners, and collaborators form a chosen family, grounding him while also amplifying his practice. Together, they create, exhibit and curate, building spaces of visibility that might not have existed otherwise. “There’s so much healing that has happened in terms of making art and curating shows with people from the same sort of upbringing and experiences as me as well. It helps me push myself, and it makes me feel more confident in putting my work out there and feeling more. Yeah, I think it’s just like a nice spot to have.”

Despite all the pain, ultimately, Ashraf’s work refuses the tired trope of the suffering artist. “None of this would have been possible if I didn’t have the love and support and the push from my immediate circle of friends and from artists who I really do love. I just don’t think this would be possible.” The ban, the exile, the precariousness — they are not romanticized in this book. They are stark, lonely conditions that cut to the bone when expressed in Ashraf’s voice. And yet, within them, the artist constructs spaces for joy, intimacy, and creation.

As our conversation winds down, I’m struck by the fact that Ashraf’s work is a site of ongoing negotiation, of constant artistic engagement. His practice is a testament to the resilience of the self in the face of bureaucratic and social erasure. It is a chronicle of queer exile, an excavation of memory, and a meditation on how one persists, and creates, when the world insists on screaming: you are not allowed here.

Ashraf’s forthcoming sequel, What Becomes of Us Here (to be published in 2026 by his new imprint, Deepstate Press), continues this delicate negotiation. He hints at the political stakes — immigration, visa restrictions, the fraught language surrounding migrants in the UK — but he is equally invested in the personal. The question at the heart of it? What it feels like “being an immigrant in this country.”

In an era when so much energy, and so many systems, work to erase immigrant lives and stories, Ashraf’s work offers an urgent counterpoint. To record. To leave evidence. Writing, photography, film — they’re all ways of saying “I was here.” We need more of them.