“Feelings can just creep up like that – I thought I was in control.” Spoken by one man, to one woman, amid dense fog and torrential rain under a humid nighttime sky. Spoken like a confession of the greatest sin known to man. Spoken like a justification or explanation, for something we can never truly understand.

Wong Kar-Wai’s In The Mood For Love (2000) follows two neighbours who discover that their spouses are having an affair with each other. As they begin to bond over their shared pain and try to understand how the affair began, the two start to develop their own complicated relationship. It’s an age-old tale of an impossible romance, where the core conflict rises from two characters forced to hold back their love. It’s impossible not to root for them, against all odds: nothing aches more than a perfect match that simply isn’t meant to be.

Turning 25 this year, the film has been heralded as one of the greatest of all time since its release, having won awards galore, being placed on nearly every critic and filmmaker’s list of favourites, and earning a spot on the regular programming of many an arthouse cinema. But, how much has romance, and our approach to romance, changed since the film’s release?

2025 is seeing a wave of antiromanticism – mainstream culture favours the convenient, practical and literal. Visual art created by generative AI is being praised for replicating the ‘skill’ and ‘technical proficiency’ of a talented painter, and there’s even a coined term for people’s increasing inability to view the world outside of their own immediate understanding (known as the ‘bean soup’ theory), which tells you how common it’s becoming.

In cinema, the confused reception of the films of Canadian auteur Celine Song, whose debut film, Past Lives (2023), drew many thematic comparisons to the films of Wong Kar-Wai, is the prime example of this trend. Her second feature, Materialists (2025), was labelled as anti-feminist ‘broke boy propaganda’ online, because a high-flying New York matchmaker, Lucy, chooses to get back together with her aspiring actor ex-boyfriend, John, rather than dating a charming millionaire.

More cynical audiences can’t understand why Lucy would choose the boyfriend who ‘isn’t making enough effort to escape being poor’, when the very same man tells her that he “sees wrinkles and children that look like her” each time he looks at her face. If two people are so obviously, clearly, in love, do we really need a filmmaker to tell us why?

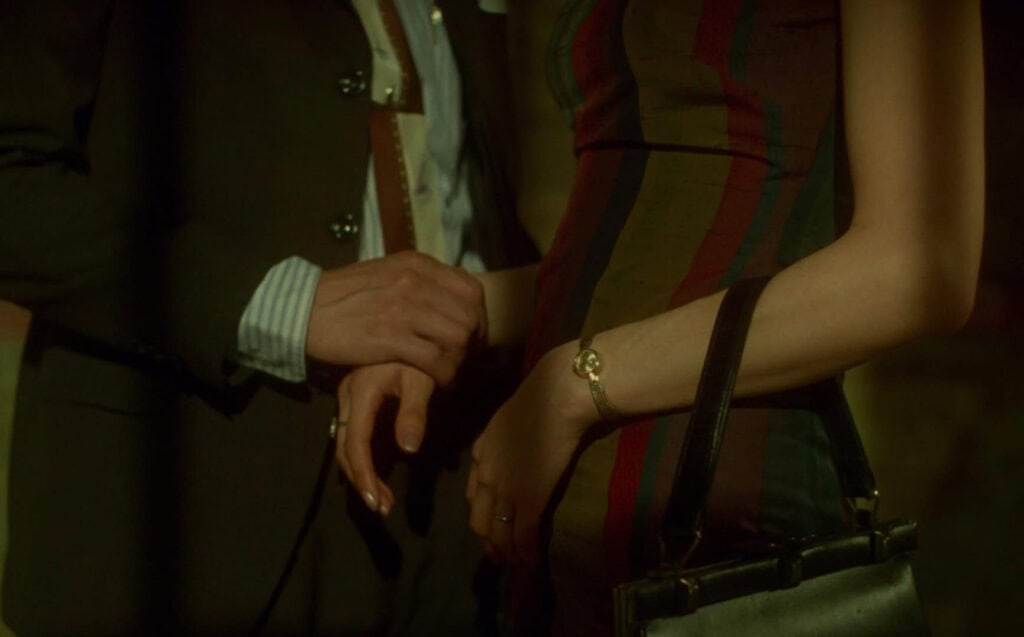

Wong Kar-Wai, praised for his atmospheric romances, takes a very similar approach to love and relationships. In Chungking Express (1994) and Fallen Angels (1995), we watch as a web of people yearning for connection fall for one another – it doesn’t matter why they fall in love, but, for some inexplicable reason, these characters are all charmed and infatuated by one another. In The Mood for Love gives us the same recipe: two people retrace the steps of their spouses’ affairs, step in one another’s shoes to prepare for confrontation with their adulterous partners, and bond over one common interest. All of a sudden, they’ve passed a point of no return.

Twenty-five years on, somehow, In The Mood For Love feels more refreshing than ever. It’s a complete product of its temporal factors: it is set in 1960s Hong Kong, heavily leaning on the sociocultural and political circumstances of the time; it epitomises a lost late 90s arthouse aesthetic style, and it bears a message of ‘leaving things in the past’ that echoed the sentiment of turning into a new millennium. And still, despite all the above, it’s a completely timeless film.

Almost paradoxically, being a product of three distinct moments in time is one of the main factors as to why it’s been able to stand the test of time so well. Watching it for the first time, the now-iconic ‘Yumeji’s Theme’ playing through fleeting encounters, the stylistic frame rate drops and immensely long takes all feel like a memento of a lost time.

Nevertheless, its themes feel more relevant now than ever: in a world where the constraints of late-stage capitalism force so many of us into heralding the practical over the romantic, a tale of an impossible yearning, where two people are simply unable to make a moral sacrifice in order to embrace their love, has become even more relatable to most of us.

A film like In The Mood For Love holds a dual power: timeless appeal as a film grants it an evolving significance. Its distinct visuals, simple yet gut-punching script, and universal central story transcend the sociopolitical undertones that make it feel so relevant now – in another 25 years, it might still be one of the most beautiful films ever made, and I can’t help but wonder if its forbidden love may take on a new meaning once again.