When Madeleine Dunnigan appears on my laptop screen, the day before her debut novel is published, she’s wearing a citrus green sweater and a smile. Pearly, wet light is leaking in through a window. She lives in London, where, I think, it is probably miserable. At the time of our conversation, the UK has hit its 41st consecutive day of rainfall and there is nowhere else I’d rather be transported to than the summer of 1976.

This is when Dunnigan’s debut, Jean, takes place. Jean is a brutal and hazy account of one boy’s coming-of-age, distilled down to one summer on the grounds of Compton Manor, a boarding school for boys with problems. It’s the summer the reservoirs dried up and Elton John and Kiki Dee hit no.1 on the charts, and, for Jean, it is the summer he falls in love.

Except this isn’t your usual campus love story. Jean – Jewish, on a scholarship, son of a single mother – is an angry soul. He beats his classmates and breaks glass. He has been kicked out of almost every school he has ever attended and Compton, it seems, is his last chance to get those ever elusive O-levels. The object of his affection is Tom, a football star who struggles with epilepsy. Both boys, already deemed “freaks” by the wider world, are desperate to escape “The House of Nutters,” as they call it, and carve out a life of their own. But the question is: will their relationship be the key to this freedom or will it destroy them?

The Cold Magazine (CM): Tomorrow is the official UK publication date for Jean. How are you feeling?

Madeleine Dunnigan (MD): I’ve just got back from New York, which was amazing, but also brutal. It’s so cold! It was minus eleven degrees. And yes, publication is tomorrow. I’m going to a few bookshops to sign copies. I’m really excited.

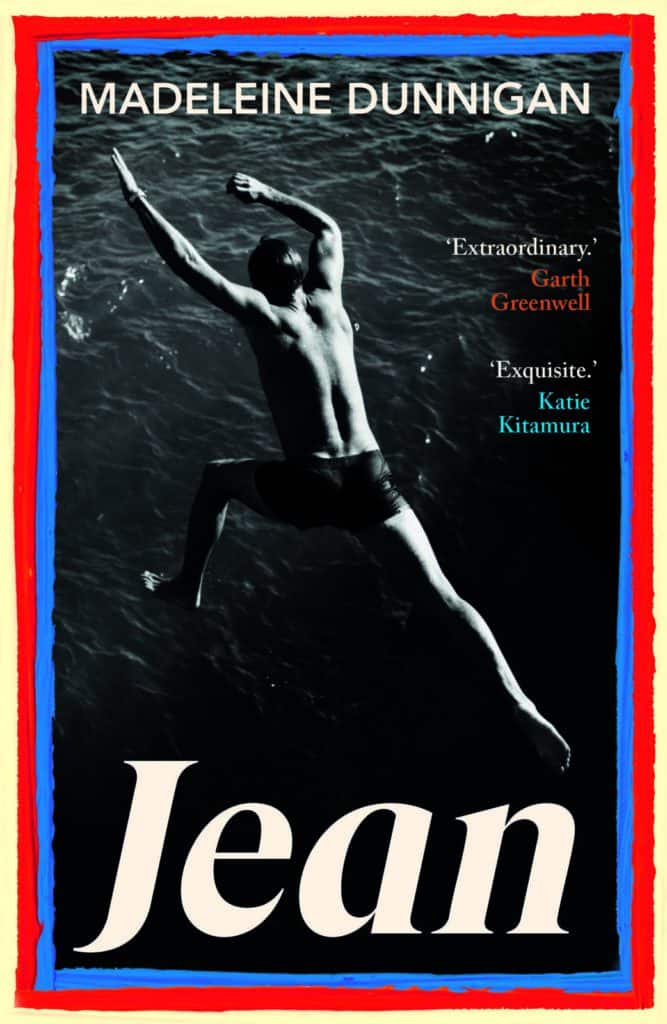

CM: The UK cover is beautiful – that black-and-white image of a young man diving into water. For me, it evokes a very specific kind of story: young men in a cloistered setting, experimenting with love and desire over a long summer, but Jean feels stranger and more dangerous than that. Were you consciously trying to break the mould?

MD: I’m really glad you asked that. For a long time, this was a very different book. It spanned eighty years and had three narratives. The boarding school section was originally much smaller. It was a halcyon place where Jean returned to in his memories, rather than being central to the story.

But as I was writing, I realised this was where the energy was. Brandon Taylor [the author] read an early draft and encouraged me to expand that section, which was enormously helpful.

I knew I wanted to write about a teenage boy in the 1970s who felt profoundly at odds with the world. The idea was very loosely inspired by a member of my family who disappeared before I was born. They left of their own volition and never came back. I was thinking about what pressures – social, cultural, psychological – might collide to create that kind of explosion.

From a craft perspective, writing is always a balance between complexity and container. You need a structure strong enough to hold the emotional and psychological material. The boarding school became that container. At times, I tried setting the story more explicitly in London, but it felt like bad fancy dress. The boarding school created a filter and contained those larger pressures that allowed Jean’s behaviour to emerge more organically.

It’s a crucible. A place where choices are limited. If he’s smoking weed by the lake, and he’s not in class, that matters. But I also knew it couldn’t be a quintessential boarding school queer narrative. Jean is too disruptive for that.

CM: Wow, so Jean’s story was inspired by a family member. Can you talk more about that?

MD: He disappeared before I was born, and I think that’s where the genesis came from: wanting to understand someone who’s very different from myself, who existed in a different time.

CM: And like your family member, the novel ends with Jean leaving and, supposedly, disappearing. Did you always know that would be the ending?

MD: Yes. A previous draft included a character very similar to myself searching for Jean. At that time, it was three novels in one. There was this queer broken love story boarding school narrative, then you had a narrative from Rosa, his mother. It was written like a confession. It was first-person, a letter. And then you had this detective narrative.

But the thing about that is that I knew Jean could never be found. If nothing new is revealed, you just repeat the same emotional beats. So for a long time, I knew that it would end with him leaving, I just didn’t know how much further I would go.

CM: Why 1976 specifically?

MD: There was an actual heat wave! It was really, really hot. But it was also politically and culturally volatile. You have the nihilism of punk reacting to earlier liberalism. The country is still haunted by the Second World War while trying to reinvent itself. There’s the looming threat of nuclear war. There was this real sense of Britain on the brink of something.

CM: I’ve seen the novel described as a romance, but I found myself wondering whether it really was a love story at all. It feels as though Jean and Tom never quite reach true intimacy.

MD: I usually call it a broken love story. It’s a story about people trying to love each other and failing. But it’s not even a failure in a simple sense. It’s about how different kinds of love can inadvertently cause harm.

So with Jean and Tom there are moments of pure love and enjoyment, but they are undermined by Jean’s inability to believe them, by his fear and insecurity, and by Tom’s inability to take the relationship seriously. In that era, especially in that environment, Tom is never going to build a life with a man. So there’s this sense that it’s always imaginary. It could never be real, and I think that Jean feels that.

But there are other forms of love, like his mother’s love. She loves him so much, and yet it’s not the way he needs to be loved, and she’s also influenced by her own brokenness. Jean and Mickey’s relationship, you know, borders on the abusive, but it’s also so meaningful for him. I wanted to show that there’s no blame, and I hope that’s what people take away from that relationship.

It’s about holding up these difficult, chaotic relationships and showing that each person is motivated by their own pathos. Like Greek characters, they have this line of fate that they can’t veer from.

CM: One of the striking things about the novel is its refusal of grand revelations. Trauma and betrayal emerge gradually – there’s no singular moment that explains everything.

MD: That’s lovely of you to say. I will fully admit, and maybe it’s helpful for the writers out there that in earlier drafts, there were big moments in earlier drafts. Everything was a moment.

The redrafting process was pulling back from those. In life, it’s very hard to pinpoint when something goes wrong. I didn’t want easy villains or easy solutions because I don’t think anyone is a pure villain. Maybe the Italian man, but even then, I suppose, I was trying to replicate the stories I heard from speaking with queer male friends. For many of them, their first sexual experiences were troubling encounters and they were affected by them, but it was woven into the fabric of life.There isn’t always a dramatic rupture.

It was about complicated relationships and trying to capture feelings of unease – the sense of things going wrong, but not fully ever really understanding why. And so the novel is aggregate, it’s this collection of things that build, until it can be nothing else.

CM: There’s a powerful passage early on about how queerness operates as an open secret at Compton Manor. Although many of the boys are sleeping with each other, Jean tells, us, “No one is, nor ever will be, a faggot.” It reminded me of Tony Kushner’s line in Angels in America: “Homosexuals are not men who sleep with other men. Homosexuals are men who know nobody and who nobody knows. Who have zero clout.” Were you thinking about the tension between identity and behaviour when writing that?

MD: Very much so. I was interested in the erasure of identity and the difference between seeing something as external to yourself versus as a part of yourself. At the time the novel is set, 1976, is a complicated moment in the history of the queer experience – homosexuality is no longer illegal, but it’s still very much a maligned identity, and is therefore associated with a specific type of figure within the cultural consciousness.

One of the parties that I originally wanted Jean to go to would have been Andrew Logan’s Alternative Miss World, which started in 1976, where he would have met people like Derek Jarman and Leigh Bowery. It was a world of costume and fantasy and high camp, and queerness as a form of rebellion and resistance.

The boarding school, on the other hand, erases that identity. It enforces a certain way of being, and tells Jean and his classmates they must be men in positions of power. And in that setting, sexual acts are separated from sexuality. You can fulfil “needs,” but you cannot be a certain kind of person.

CM:The further you go into the novel, it becomes almost like an inkblot test. You could come away thinking Rosa is monstrous and neglectful. Or you could see her as someone in immense pain, doing her best with a son who is violent, unreachable, expelled from every school.

MD: I’m really glad you say that, because that was the intention – to complicate, not to judge. Everyone who reads it seems to align differently. Some people see Rosa as unforgivable. Others feel enormous sympathy for her.

I feel very sympathetic toward Rosa. In some ways she’s the character I can most easily imagine myself as – overwhelmed, isolated, trying to parent a child she cannot reach.

CM: I felt that too. There were moments, particularly in the phone calls between Jean and Rosa, where I was visibly wincing at how cruel he is to her. Jean can be frightening. He’s mean. Even the way he treats animals is unsettling. Did it feel like a leap of faith to make your protagonist someone readers might struggle to root for?

MD: It never felt like I was writing someone I didn’t want to root for, because I felt such compassion for him. The broader exercise of the novel was empathy. I was thinking about a figure I only knew from stories – when you line up all the anecdotes about someone, you get a certain picture. I wanted to get behind that picture and imagine what it felt like to be inside it.

So writing Jean was an act of compassion. There were moments where I wondered, is this too much? But that’s partly why the setting became so important. It softens him. It gives him space to experience pleasure, to shine, to feel something like peace.

Madeleine Dunnigan’s Jean, published by Daunt Books, was released in the UK on 12 February 2026.