There’s something ancient about the way we gather to eat; something theatrical, absurd, and revealing. Roman banquets, velvet cafés, white tablecloth restaurants: across time and place, the dining table has always been a stage for pleasure and performance, a place where class divides are sharpened by silverware and momentarily glossed over with butter and wine. In Jack Penny’s latest body of work, CHEFS, the restaurant–now set in the wilds of the Alps–becomes a site of gluttony, control, and chaos, where the chef, much like the artist, reigns supreme. The series was first shown at Château La Coste back in March, a Provence estate renowned for its art programme, in one of its on-site galleries.

Penny, born in 1988 in Portsmouth and now based in the coastal village of Bosham, West Sussex, is known for his loose, expressive paintings of contemporary life. His figures stumble through late-night bars, black-tie dinners, and private dramas, always on the edge of collapse. In this series, those dynamics converge in the figure of the chef: commanding yet depersonalised, cloaked in crisp whites and culinary authority. “You almost become unaccountable for your actions when you’re in uniform,” Penny later notes. Here, the chef appears to give in to madness, driven to the edge by ritual, repetition and expectation. Though rendered with humour and spontaneity, the series probes deeper systems: the roles we play, the masks we wear, and the instincts we try (and in this case fail) to suppress.

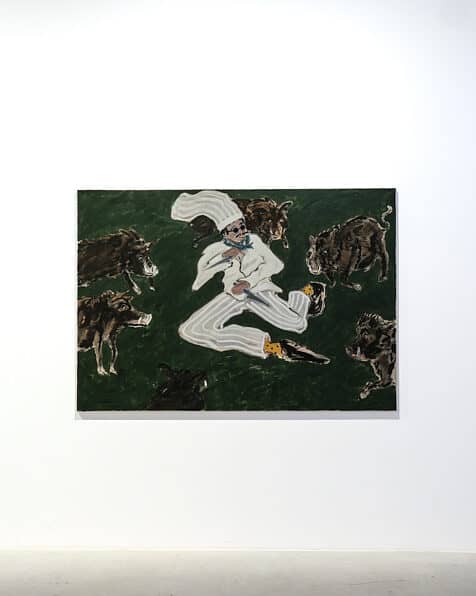

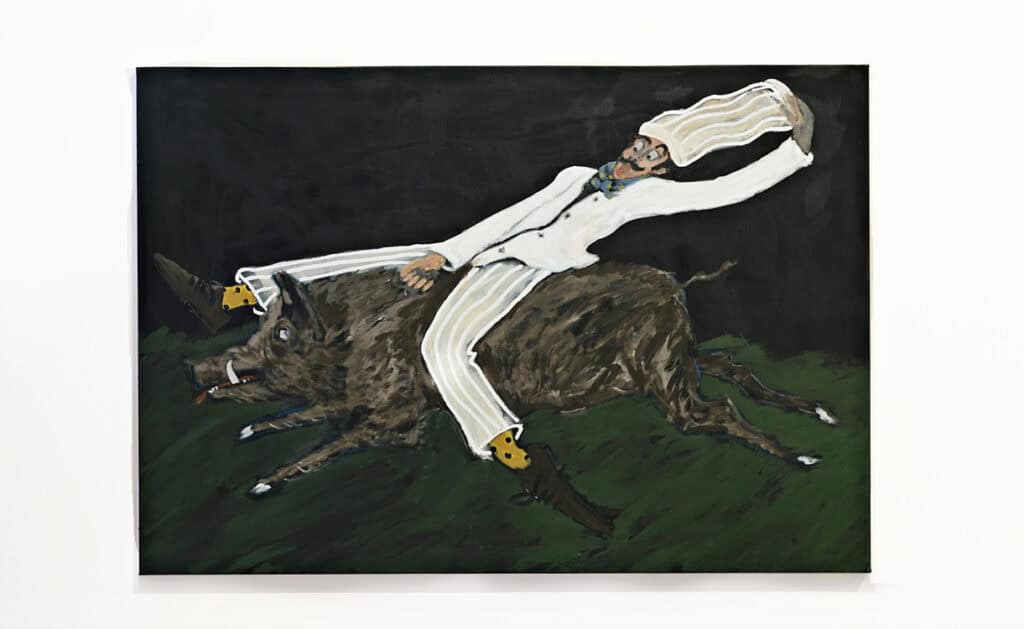

This tension between appetite and restraint runs through the entire series. Gluttony, one of the original deadly sins, might seem outdated, but Penny’s paintings suggest otherwise. In a world of endless choice, bottomless brunches, and a for-you page of curated indulgence, our hedonism is no longer a private vice but rather a public engine. We’re encouraged to consume constantly, not for survival, but to sustain a capitalist economy built on excess and artificial needs. Penny’s dinner scenes lean into this contradiction. At once ecstatic and grotesque, they expose the strain beneath pleasure and the absurdity behind the spectacle. In his work, nature seems to push back: wolves creep in, wild boars snarl at the edges, and the systems holding everything together begin to fray. It’s as if the natural world is no longer content to sit quietly outside the window, but is ready to reclaim its place from a society gorging itself toward ecological collapse.

Food appears across Penny’s work like a recurring dream: figures feasting, drinking, performing. I first encountered one of his paintings in a restaurant, surrounded by half-empty glasses and too many plates, and it made immediate sense. His work belongs to that strange, late-hour mood, when the conversation starts to unravel and pleasure tips into excess. I remember thinking, this feels like the last hour of a very long dinner party; I’m tipsy, someone’s pouring more red, and I’ve just eaten the final sliver of cheese I definitely didn’t need (and will regret the next day).

The Cold Magazine (CM): Where did the idea for CHEFS begin? What drew you to the uniform of the chef as a symbol?

Jack Penny (JP): As with a lot of my characters, it started with the aesthetics. I’ve always been fascinated by uniforms; they’re striking, and there’s a certain bravado to them. There’s something about putting on a uniform that makes you almost unaccountable for your actions.

With the chef, it was partly about the silhouette – I loved that structure of white. It’s such a fun form to paint. And then there’s the ridiculous hat. Originally, I just wanted to use a white uniform and thought, “What works?” I paint a lot of restaurant scenes, so I landed on the chef. It was originally meant to be a one-off, but then I got offered a show at Château La Coste, which is also known for its food and wine. It felt like the perfect fit, and the series just grew.

I often use glasses to remove identity; I want people to see themselves in the situation, not a particular character. The chefs became that too, just a symbol. The series became more about human behaviour and how ridiculous we can be as a group.

I always say my paintings are like a joke without a punchline. And it’s funny, because I’m not even a foodie. I like food, sure, but I’m not chasing the next Michelin star restaurant. Since painting chefs, loads of restaurants have assumed I’m obsessed with food, and I’m really not. I’m probably no more into it than the average person.

CM: Food seems to be a recurring theme in your work; characters dining, drinking, and celebrating. Despite not being a foodie, what is it about food that feels so potent as a subject or setting?

JP: Exactly that – it’s a setting. We all eat. It’s something everyone can relate to.

Most of the time, my paintings are set in fairly upmarket restaurant environments, and I use them as a microcosm to talk about society. On the surface it might just look like chaos, disaster unfolding, but underneath, there’s something about the blue-collar and white-collar worlds meeting in a space with really high expectations.

Everyone’s under pressure in a restaurant like that. The chef’s under pressure, the waiter’s under pressure, and often the clients are too. That makes it a great environment to observe both the darker and lighter sides of human behaviour.

I like that the surface of the work feels light; it makes it easier to approach. But hopefully, when you strip it back, there’s more going on than just a restaurant scene. I don’t want to spell anything out or get too political. I want the work to offer a bit of relief from the seriousness of everything.

There’s definitely that undercurrent about power, and misused power. I’ve always had a natural disdain for it. Even as a kid, I didn’t understand why someone should get to tell someone else what to do.

Maybe I paint about it because I struggle to talk about it–I’m super dyslexic.

One of the paintings in the series, Napkins (Study), 2025, seems to reference the French ritual of eating the ortolan bird – a brutal, baroque tradition where diners hide their faces beneath cloths as they consume the tiny, drowned creature whole. I had a question prepared about that. But after Jack insisted he wasn’t all that into food, I let it slide. Still, the references feel too good to be accidental. Anonymity, indulgence and shame all collapsed into one white napkin. Pretty sharp stuff for someone who swears he’s not a foodie.

CM: I noticed that in the series there’s a strong contrast between discipline and disorder — haute cuisine versus wild, snarling nature (like in Wild Boar and Through The Trees). How do you see that tension playing out, and why do you think it matters to you?

JP: Because I think that is me. I’m someone who’s quite together, quite organised, but I’ve also got a self-destructive side. I think we all do, to a degree. Painting is a way of balancing that, or letting it out a bit.

I remember as a kid, I’d have these intrusive thoughts. I’d be at a dinner table where everyone’s on their best behaviour, and I’d think, “What if I just lobbed my plate against the wall?” Not because I wanted to ruin anything–I’d never do it–but just to disturb the peace, to see what would happen. Or I’d be on the back of my dad’s motorbike when he was going fast and think, “What if I just jumped off?” Obviously, I wouldn’t, but it’s that little voice, that impulse to disrupt.

That side of me really comes out in social settings where everyone’s playing their part. And it’s in the work too: the tension between order and chaos.

But I promise I’m quite nice to have dinner with. I hope.

CM: How much do you see CHEFS as satirical? You mentioned wanting to stay away from politics, but were you aiming to critique restaurant culture, or something broader about performance and systems in general?

JP: It’s more about performance and systems in general, I think. The restaurant’s just a setting, a kind of representation of the wider world.

I did work in restaurants when I was younger. I was a potwash, and actually, that’s where I met my wife. She was a waitress. We didn’t get together until years later, but I always remember our first proper interaction.

I had this system where I’d stack the big cooking trays on this tiny, thin shelf above the sink – and it wasn’t a great system. One day, one of the trays, just by chance, happened to be full of chicken fat. I’d added a bit of water to try and break it down, and it slipped. It fell straight off the shelf and absolutely drenched me. I had to be sent home. And that’s her first memory of me – just standing there, covered in chicken fat.

CM: In some ways, both chefs and artists are creators. Do you feel a kinship with the chefs you’re painting?

JP: Yes! That’s how the series really developed; the meaning of the chefs became clearer as I kept painting them.

And I know some chefs. They’re famously all-in. It’s not a job, it’s a lifestyle. It’s every waking hour. Especially at the top end – it’s intense, it’s cut-throat.

There’s a massive similarity there with being an artist. You don’t clock off. That’s it, you’re in. You can’t really half-arse it. You can’t be a vocational chef, and you can’t be a vocational artist either, not really. I guess some people manage that, but for me, it’s become this proper addiction.

If I’m not painting every day… if I take a couple of days off, I feel off. Even if I’m on a family holiday, by the end of the week, I’m dying to get back in the studio. There’s only so much sitting by a pool I can take.

So yeah – well spotted. Artists and chefs are similar. Not many jobs are like that, but when you’re in, you’re fully in.

CM: The way you paint is also quite reminiscent of German Expressionism – it reminded me a bit of Kirchner, especially with the glasses. Are there particular artists or movements you find yourself returning to?

JP: Again, really well noticed! My first love was German Expressionism. There’s a grittiness, a darkness in it. I’ve always enjoyed dangerous work, something a bit gruesome or unhinged.

Lots of artists, like George Grosz and his peers, I still go back to. And in general, I’ve always liked German painters.

I remember the first time I got excited about art, I was around thirteen. I had a five-years older friend, and he was into art before most people were. I was looking through his bookshelf one day and came across a Ralph Steadman book, the guy who illustrated Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. It just blew my mind. I was already into painting and drawing, but that was a moment of, woahhh. The marriage of Hunter S. Thompson and Ralph Steadman was just perfect.

That was the first big moment for me. The second would be seeing the Richard Diebenkorn retrospective at the Royal Academy. That really floored me. I’m not saying I paint like him, but the calibre of painting, the confidence, the looseness… I think that was when I properly fell in love with painting.

CM: Do you feel like it’s something more formal that draws you to these influences, for example, the colour, the distortion, the energy, or do you think it’s something more visceral and emotional?

JP: I think it’s the emotional. I like work where the aim isn’t just to make a good painting. And I’ve got time for nice paintings, I do. But I’m not interested in making something that’s just goal-oriented or polished. Other artists can do that much better than I can.

I’ve got this undertone, this kind of instinct to be destructive, and I think that comes through in my work. Or at least I hope it does. The reason I started using humour–slapstick, end-of-the-pier, lowbrow–is because about three years ago, I felt really stuck. I didn’t know where to go with my work. I was trying to make something slightly original. I’m not saying my work is original–it’s all derivatives, really–but I needed a way to feel free again.

As soon as I permitted myself to add a bit of “I’m not taking this as seriously as you think I am,” I could suddenly take the work seriously again. It took the pressure off.

Since then, I’ve realised that if I don’t laugh at some point while I’m making a painting, I’m not enjoying it. I need to be amused by the ridiculousness of the imagery, or by the colours being slightly off, or by something barely holding together but just working.

If a painting comes together too easily, I’ll usually take it back into deep water. Because even though my work might look light or commercial on the surface, I want there to be a history in the paint. It needs to feel like it’s gone through something. Like, there’s been a bit of a battle behind it.

CM: What’s next – either in the studio or outside of it?

JP: I had a really busy year last year. I’ve just had a baby! At the moment, I’m enjoying that vibe. I meant to slow down, but then ended up doing a last-minute show at the start of the year. Made the whole thing in two months, which was full-on.

Now I’m working towards my next show, which will be at Elveden Hall, this incredible old manor house that has never been open to the public. They’re opening it for the first time for The Dot Project X HeritageXplore artist residency scheme and later for the exhibition, which is amazing.

In between that, I’ve been really getting into this new series. I read a book about this guy called Percy Fawcett, an explorer from the 1920s who was one of the best map drawers in the world. He got sent to the Amazon when the West was racing to map the whole planet, and the Amazon was one of the last unmapped places.

Most of the explorers they sent would die within a week due to the climate, the terrain, and the tribes. Some of them were cannibals and things. But Fawcett was a beast; he survived loads of missions. Eventually, he found ruins and became convinced there was a civilisation there that completely challenged what the West thought South America was capable of.

And then he vanished. No one knows what happened. That whole story–the obsession, the jungle, the discomfort–it just really grabbed me.

So I’m working on a series loosely based on that world. It’s about the wildness of it–the inhospitable climate, the heat–and how soft we are now, with our central heating and cars. That contrast really appeals to me. It’s a break from what I’m more known for. I’ll be balancing that with the Elveden Hall work; one’s about the wild, and the other’s about Empire and interiors and performance. They balance each other out perfectly, I think.

Jack Penny’s next exhibition, Old Country, will be on view at Elveden Hall, Suffolk, from 1–26 October 2025. The works will be developed during a two-month residency at the hall (1 August – 30 September), as part of a collaboration between The Dot Project and Heritagexplore. Set in a stately home steeped in empire, tradition and reinvention, Old Country will continue Penny’s exploration of belonging, social performance, and the tensions simmering beneath civility.