AT A TIME WHERE THE WORLD FOUND ITSELF AT A TURNING POINT BETWEEN THE ANALOGUE AND THE DIGITAL, JEAN PAUL GAULTIER’S AW1995 READY-TO-WEAR SHOW WAS EXACTLY WHAT THE PEOPLE NEEDED TO SPAN THE GAP BETWEEN THE FASHION AND THE FUTURE.

Dubbed “Best Show Ever” in Vogue’s video series in 2020, Jean Paul Gaultier’s Autumn/Winter 1995 ready-to-wear show, often referred to as ‘Cyber‘, still feels like fashion doing what it does best, turning an artistic display into the designer’s point of view.

Before the clothes even had a chance to speak, the runway did. The show opened with two women roaring down the centre of the catwalk on a motorbike, an entrance fashion writer Laird Borrelli-Persson remembers plainly: “It opened with two women on a motorbike coming in.” The passenger hopped off to DJ for the evening, what Gaultier himself described as “the girl that was a DJ and doing the music”, and the message landed fast: this wasn’t going to be polite fashion.

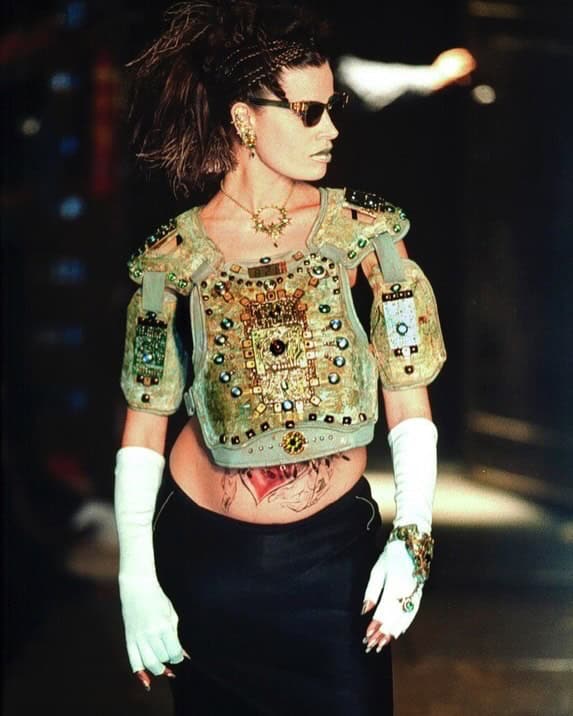

Look one made that even clearer. Model Claudia Huidobro walked out visibly pregnant, her belly tattooed, a moment she later recalled with proud simplicity: “And I was quite pregnant… with a tattoo on my tummy.” During Vogue’s documentary by Joe Pickard and Kimberly Arms, Estelle Lefébure remembers Gaultier’s approach to the casting with the same mix of tenderness and nerve: “I want you to be beautiful… are you okay if we show your belly?” For Gaultier it was never about the body being something to hide or “correct,” it was the vessel that carried the show’s entire point, unapologetic distinctiveness.

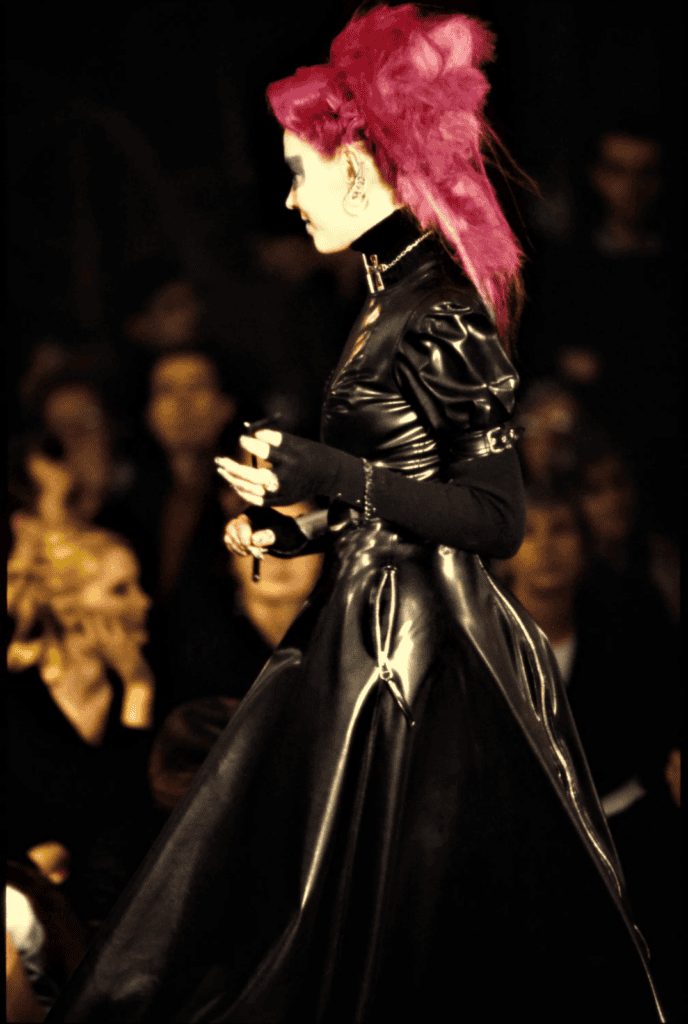

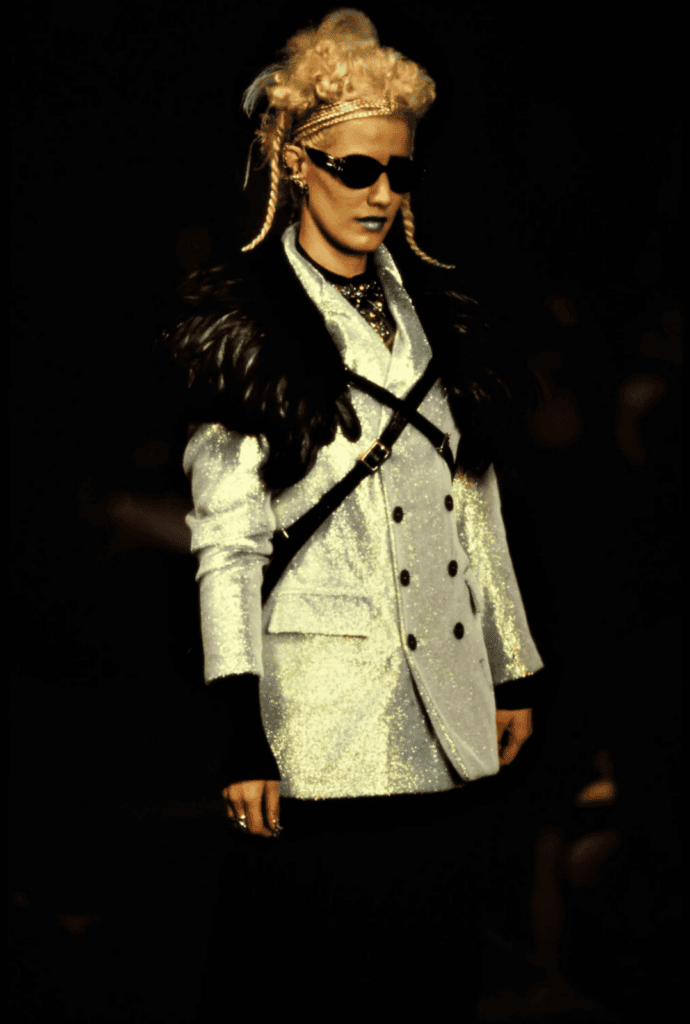

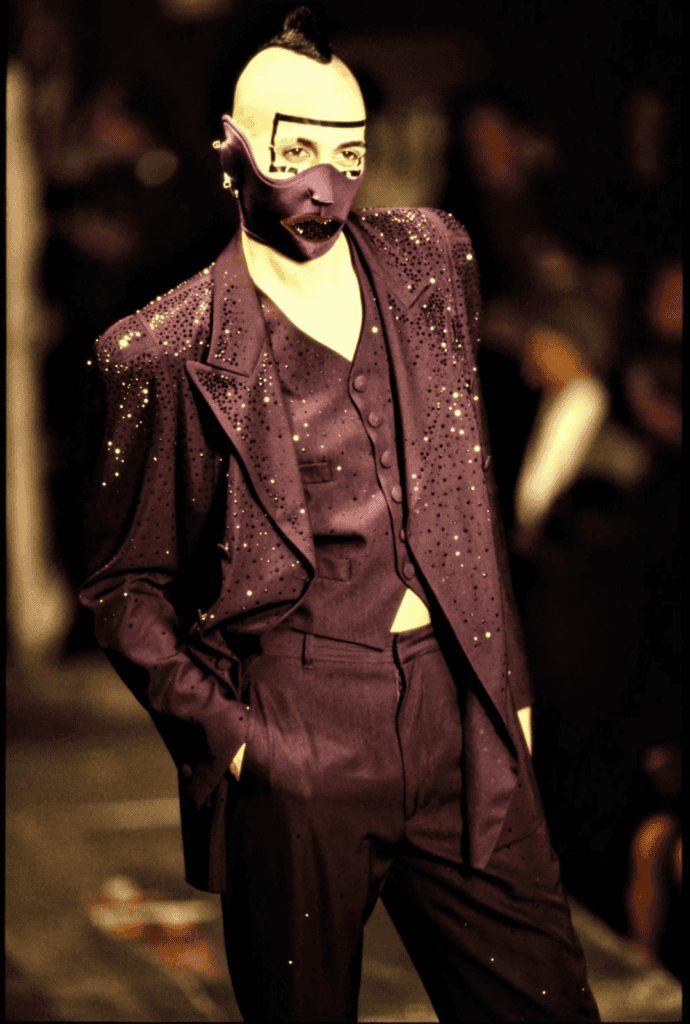

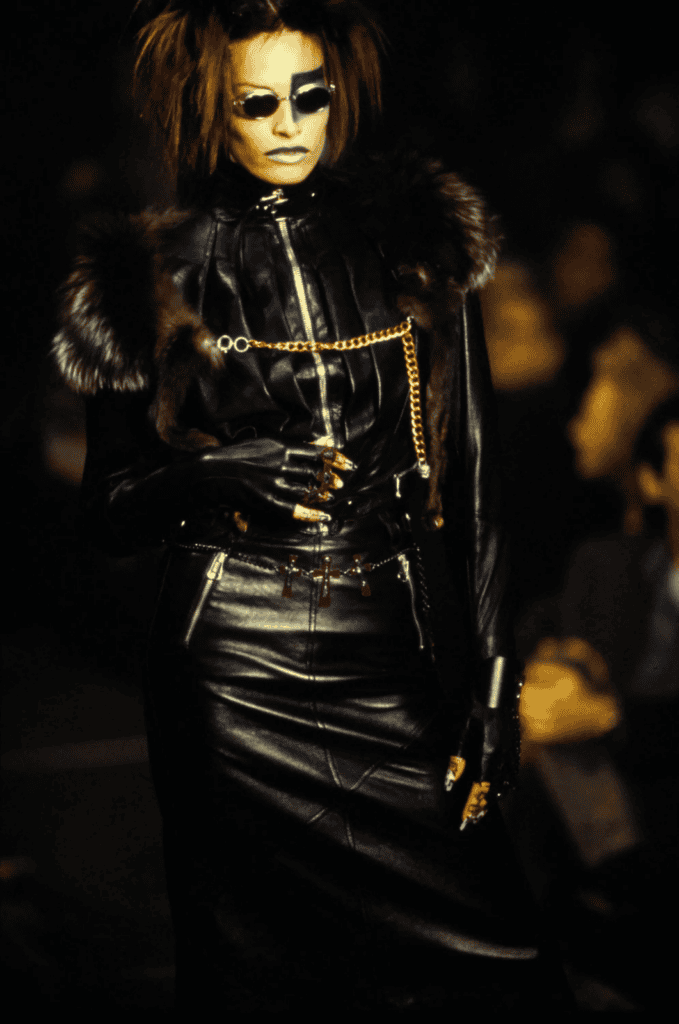

That focus on the body, active, present, and allowed to be itself, became the collection’s backbone. Gaultier didn’t treat clothing as a layer to drape over a passive figure; he used garments to sharpen and exaggerate anatomical lines, to make silhouettes feel engineered, and to invite interaction. The result was a runway where the body read more like a performer. Moving through the space, framed by the clothes, occasionally challenged by them, and never reduced to mere decoration. The collection celebrated club culture and difference.

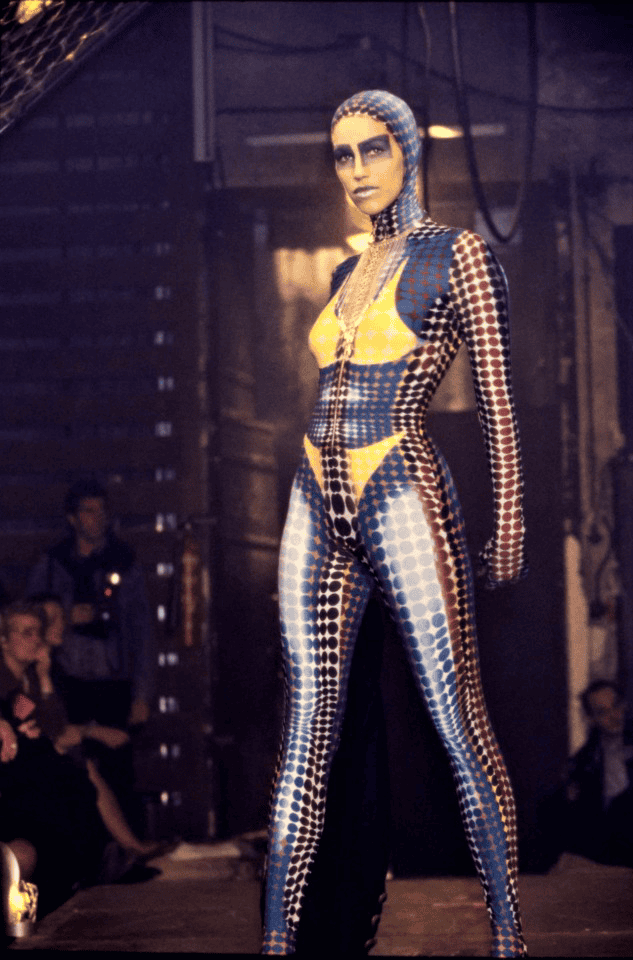

The collection’s most striking visual argument came through second-skin bodysuits and body-mapped patterning. The show’s runway notes connect these pieces to optical artist Victor Vasarely, whose illusory compositions helped shape the show’s warped gradients and “computer-designed dot prints” that modelled the figure like a digital mirage. These bodysuits weren’t “tech” in the literal sense, no sci-fi props required, but they looked like the body had been scanned, rendered, and reprinted back into flesh. Worn beneath anorak-like outer layers, zippered ball dresses, and ski-suit gowns, the effect was less costume than interface: skin becoming a surface for illusion, with tailoring acting as the translator.

What’s clever is that the collection didn’t stage “technology vs. craft” as a fight. It folded the digital mood of the mid-1990s into fashion’s most physical language: pattern-cutting, beading, and construction. In other words, the show didn’t reject technology; it metabolised it. That’s exactly the kind of historical thread Borrelli-Persson highlights when she says, “It’s very important to trace how designers… have reacted to technology and ideas of the future in fashion.”

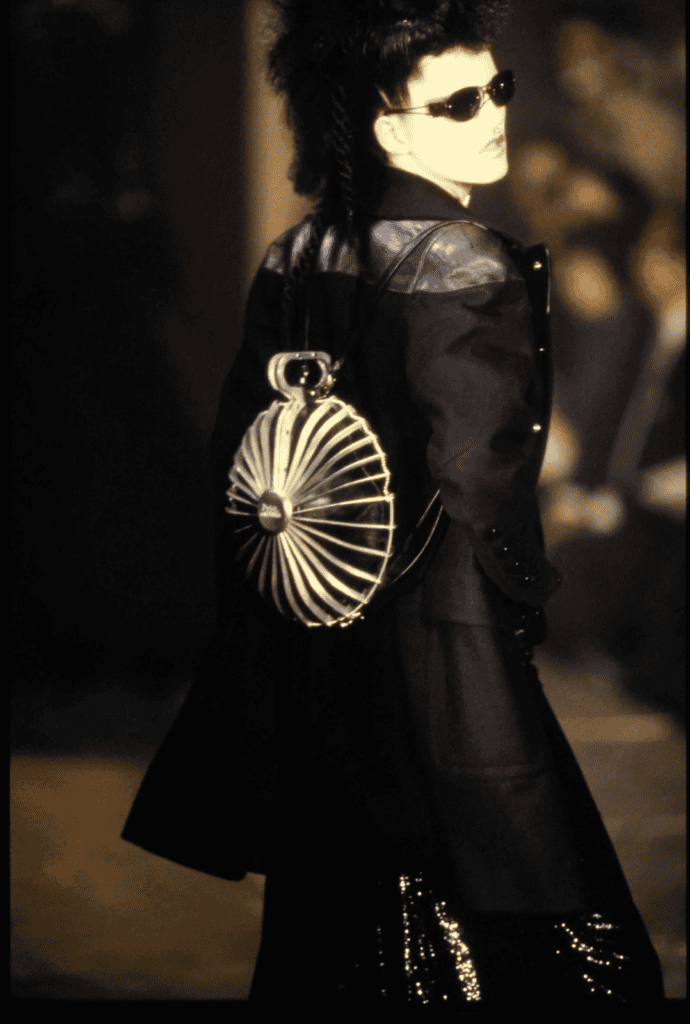

Then came the details that made the idea feel tangible: “light-up armour-like pieces” and embroideries that “resembled the pattern of a motherboard.” In the Vogue video, Borrelli-Persson makes the reference even more direct: “Some of the embroideries were actually based on a computer chip.” This is where the show gets deliciously paradoxical: the most futuristic motifs, microchips, circuitry, illumination, arrive via the most traditional means. Beads imitate hardware. Embroidery stands in for engineering. Armour becomes adornment, and adornment becomes a comment on power.

If the clothes made the future seductive, the staging made it funny, because Gaultier rarely delivered an idea without a wink. In Vogue’s runway notes, he described the mood with a throwaway phrase to Tim Blanks: “Mad Maxette.” That one word does a lot of work. It frames the show as post-apocalyptic, yes, but also knowingly stylised, flirtatious, and unapologetically feminine. The imagined Gaultier woman was not a victim of the future, but rather she was its author, dictating what goes and what stays, what’s in and what’s out. Though she has the power of technology on her side, she runs the function as her own. As Vogue’s runway report quotes him, she is “courageous, confident, and very much in control of her life.”

The show’s impact comes from the sense that many kinds of women were allowed to carry it. Model Carmen Dell’Orefice’s line is the one that sticks because it’s both simple and specific, how “he allows everybody their individuality.” That’s not just a nice sentiment but an editorial stance of how he, as a designer, wants his work to be interpreted and, more importantly, worn. Against a decade often remembered for tight ideals and controlled runway polish, Gaultier’s world made space for personality and for bodies that didn’t behave like standard hangers.

There’s one historical detail worth clarifying because it adds to the show’s myth. Although the collection is known as AW95 ready-to-wear, the collection was presented in Paris in March 1994, which is part of why it feels so ahead; it arrives early, then lives long in the cultural imagination. The 1990s were already vibrating with change: the accelerating presence of digital imagery and new anxieties about what “the future” would do to bodies, especially women’s bodies. Gaultier didn’t respond with distance or dread. He responded by putting the body centre-stage and letting fashion do what technology couldn’t, make the future feel so… intimate.

Looking back, the Autumn/Winter 1995 show reads as a key expression of 1990s fashion thinking, not because it predicted a specific device or trend, but because it reframed the relationship between body and modernity. The clothes propose that innovation and sensuality aren’t enemies. The casting proposes that futurism doesn’t require uniformity. And the runway itself proposes that fashion’s best critiques often arrive disguised as entertainment, loud music, roaring engines, a tattooed belly, and a designer’s grin knowing he has accomplished what we had set out to do.