The name Alber Elbaz is synonymous with a unique type of vision, one that defined Lanvin’s golden age and produced a series of legendary collections. Championing both aesthetics and an undeniable élan, Elbaz blurred the line between fashion and art through collections that impactfully created silhouettes for the modern woman. Ever since his last collection in 2015, followed by his death from COVID in 2021, Lanvin has struggled to maintain its former prestige.

Elbaz, who reimagined the fashion landscape of the early 2000s, once famously quipped, “My job is to make women beautiful” with his humble approach towards dressing some of Hollywood’s most illustrious. He was fresh, original, and cinematic, paying tribute to some of Jeanne Lanvin’s early Art Deco inspirations.

Blessed with a voracious appetite for life, the designer’s passion for storytelling was visible in each collection. Historically, Lanvin has occupied a niche space within the industry, a space few other brands have maintained. Veering off the course of mainstream luxury, Lanvin neither screams for attention, nor whispers, but sits within the space that the brand has carved out for itself over time.

Luxury fashion and good PR are like fine wine and cheese: each can survive on its own, but together the pairing proves ideal. Since Elbaz’s death, collections have failed to achieve the same level of momentum and campaigns struggle to resonate. Today, one must ask: is nostalgia the only thing keeping the brand alive?

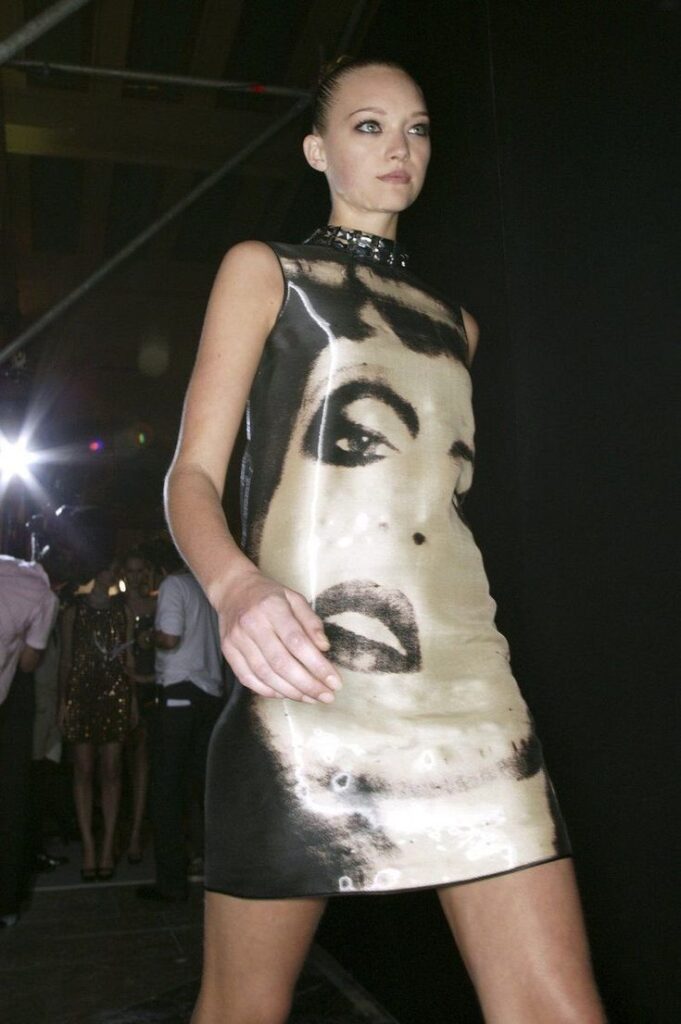

Elbaz’s SS07 collection had it all: jacquards, Grecian drapery, and decadent trompe l’oeil constructions–glamour in its highest iterations. Through a radiant colour palette and a repurposing of the house’s iconic eveningwear, he presented a future-minded elegance ahead of its time.

Back then, a brand didn’t need to court influencers and succumb to celebrities to be considered de rigueur; the industry wasn’t fully democratised yet. A posthumous Vogue article later described Elbaz as “an ace at crafting irresistibly seductive forms”, detailing his impact on the industry in a series of colourful, vivacious shots. Today, however, Lanvin no longer commands such excitement. The clothes struggle to connect with either legacy or contemporary sensibilities.

Financially, the setbacks reflect that decline. Revenue for the first half of 2025 reportedly fell to around £25 million: a continuation of the 23% sales drop in 2024. David Chan, the Lanvin Group CFO, has since stepped down. Creative leadership has been equally inconsistent. While Elbaz remains widely regarded as the designer who revived the house, those who followed, including Bouchra Jarrar and Oliver Lapidus, stayed too briefly to establish a renewed identity. House codes like the iconic dusty blue and feminine silhouettes persist, but without the emotional power they once carried.

The most notable success of recent years is surprisingly casual: the Curb Sneaker. A product of 90s skate culture, its chunky laces and playful design have struck a chord with streetwear audiences. Debuting under Bruno Sialelli in 2020, the shoe became a commercial lifeline. Yet a single shoe cannot restore a luxury house.

“Lanvin stands apart as the oldest French couture house still in operation…while many French houses express power, Lanvin expresses grace” notes Nino Downes, a representative from Lanvin who spoke with the Cold. “In 2025, this heritage translates through a contemporary lens — pieces that feel both classic and current.” In earnest, the garments available today part ways with that ethos. Underwhelming fabrications and silhouettes have replaced sensual elegance: the clothes simply do not carry enough weight.

Enter Peter Copping, appointed in September 2024 to restore coherence. Immersing himself in the archives, he presented a January debut praised by critics for reintroducing refinement. Yet the October collection told another story. Shown in a cobalt-blue space, the looks appeared clunky, at times even kitsch: washed robes de style, frantic prints, heavy over-styling. Ballet Russes -inspired headwraps nodded to history, yet risked frumpiness. The house’s commitment to elegance seemed lost in translation.

While other brands have expanded into lifestyle, enriching cultural dialogue, Lanvin remains tethered to its old quiet-luxury positioning, leaving it out of step with the zeitgeist. Two decades ago, it ruled editorials and red carpets. Today, few outside of fashion’s inner circles recognise its relevance. The question looms: WTF happened to Lanvin?

Not all luxury brands withstand the test of time. A myriad of factors indicates why some brands come in and out of the spotlight. Houses such as Pierre Cardin, Vionnet, Sonia Rykiel, and Courrèges all used to enjoy greater levels of prestige, yet now rely heavily on nostalgia, clutching the past to generate present revenue. If corporate and creative elements do not work together seamlessly, Lanvin risks a similar fate.

Across the channel, Burberry, a house even older than Lanvin, remains firmly in favour thanks to the power of its iconic gabardine trench and sharp, strategic marketing. Saint Laurent has expanded into film to secure its cultural footprint. These bold moves ensure continued relevance, attracting new audiences. Since Copping’s arrival, Lanvin has yet to take a comparable risk, and absence of risk inevitably reads as absence of direction.

Business structures further complicate the brand’s position. The fashion industry continues to be rapidly monopolised by conglomerates like Kering and LVMH–businesses capable of providing resources, stability, and cultural muscle. Lanvin, however, sits within the Lanvin Group, a younger Chinese enterprise with ambitions to compete at a higher level.

But, ambition alone cannot match decades of cultural dominance. Since taking ownership, the brand has fallen from first to third place within the portfolio in under a year, and in 2025, for a house not protected by a fashion giant, keeping pace becomes increasingly difficult.

Window-shopping on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré confirms the disconnect. Displays that once exuded glamorous fantasy now feel muted and safe. Inside, the lingering codes of the house remain, but without the emotional electricity that once defined them. The decline of Lanvin cannot be pinned solely on creative directors or on a press team–it reflects a wider shift in how fast fashion cycles, changing markets, and brand fatigue have reshaped the rules of luxury.

Recent strategic adjustments – wholesale consolidation, market emphasis shifting to Japan and the US, weaker positioning in EMEA and China – signal a brand attempting to steady itself. Meanwhile, campaigns tell a different story. Where once whimsical art direction made stars like Coco Rocha and Lily Donaldson feel mythical, AW25 opts for industrial minimalism that risks appearing dull rather than refined.

The gap between product, image, and audience becomes increasingly visible. Copping’s tenure still offers hope, but how will his creativity be challenged? A McKinsey report warns that luxury revenue shortfalls may persist until 2027, and the relentless turnover of creative leadership gives little room for gradual evolution.

Lanvin needs more than a cult sneaker or a single standout show; it needs a cohesive shift in voice, ambition, and cultural participation. Cheng Yi’s appointment as global ambassador strengthens ties to China, but does little to expand global desirability. Stability behind the scenes, including newly appointed CFO Jiyang Han, will matter only if matched by bolder creative and communication strategy.

To secure its future, Lanvin must look beyond nostalgia and reach a level of global prominence, offering audiences something unique in the process. For a brand this legendary, a resurgence is only possible if several tactful, well-orchestrated strategies are implemented. Not a single collection, product, or campaign, but a full-scale revamp of Jeanne Lanvin’s vision.