In the accompanying poem for his solo exhibition at Pilar Corrias, Manuel Mathieu does not mince his words. In three stanzas, he conjures images of sweat turning to oceans among a genocide of stars, of the devil sucking him like ice as his hopes crumble like ash in the wind. A warning – “don’t forget the weight of your sins / as the skeletons of your past become your altar” – is equally affronting. These lines are an indictment of our tendency to pave over the cracks of oppression, an invocation of the rage that’s long marked narratives around violence and emancipation.

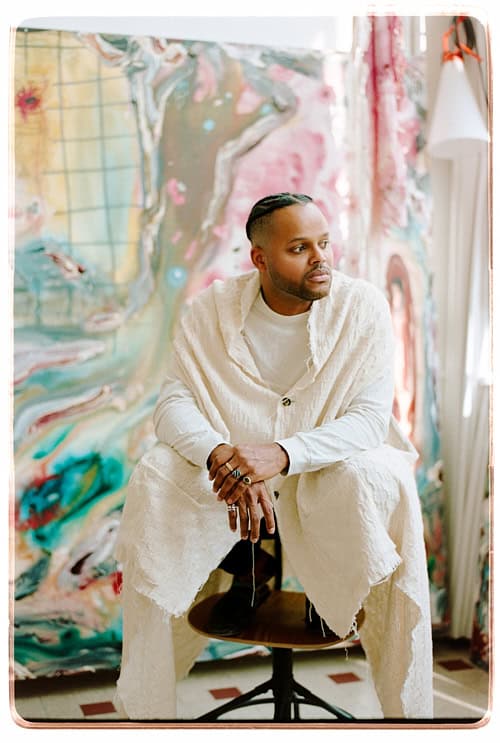

But speaking with Mathieu over Zoom, I am met by a man who feels remarkably free of rage. The Haitian-born, Montreal-based artist is in Guadeloupe. It’s seven in the morning and a lizard works its way up a post supporting the patio. He was a bit nervous about my questions, he admits, and he has prepared a list of answers to some of the trickier ones. “It’s because of how much the subject matters,” he says.

Weaving through Mathieu’s wide-ranging catalogue of sculptures, paintings, films, installations, and even fragrances, a pervading question links the extraordinarily diverse experiments: what does it mean to move through collective trauma? In 2024’s The End of Figuration, he uses abstraction across multiple mediums to map the emotional terrains often left unexplored in our reckonings with the present – from intergenerational suffering to intimacy. A standout piece forms a literal border between two spaces at De La Warr Pavilion, evoking everyday objects as stand-ins for the emotional residue left behind by migration. In Pendulum, his short film currently on view at the Saint-Louis Art Museum, he explores what lies beyond emancipation. What happens once freedom is realised?

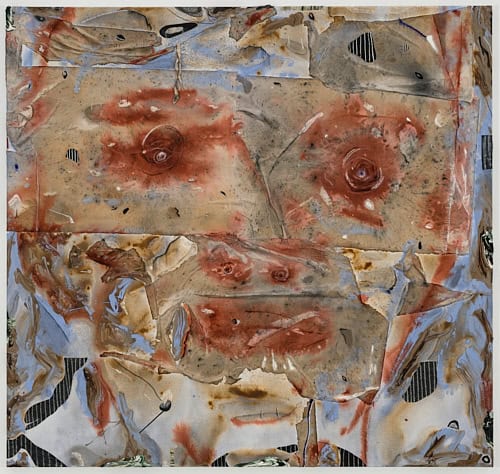

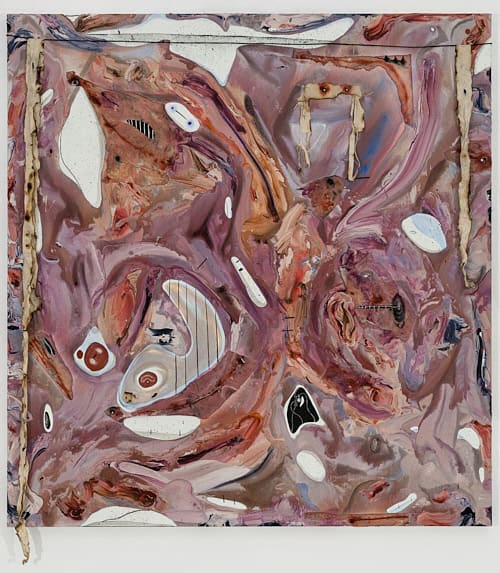

Bury Your Masters offers a tentative answer. In eight new compositions strung out in moments of movement and contrast, Mathieu gives expression to a chaotic blend of abstraction and figuration. In the heart of the revolution 2 presents torn and blackened pieces of fabric as they hang outside the frame, cascading downwards. Elsewhere, rusted echoes of a face are visible under layers of distortion in Self Preservation. What remains beneath these experiments in technical innovation is a call for re-education. By reckoning with the accepted knowledge that governs our discussions around race, equality, and colonialism, these works point to an as-yet unrealised future, free from historical hangovers—a world we might reach once we’ve buried our masters.

When I called Mathieu, the sun was rising in the corner of the computer frame. We spoke about experimentation, the surprising overlaps between contrasting techniques, reparations, and why now is the right time to create Bury Your Masters.

The Cold Magazine (CM): Walk me through a day in the studio.

Manuel Mathieu (MM): It starts with biking to the studio, then I look at my plants, make tea, burn incense. I move my paintings around—some I’m still working on, others I’ve decided to stop. I hide those ones. Then I sit and think. On a good day, I’ll get an idea that I can carry with me into the next day and sometimes, that concept will keep shedding its skin until I get to the core of it. From that point, I create what’s urgent and necessary.

CM: Is your process one of discovery or externalisation and communication?

MM: It’s a process of research, putting things together and seeing what sticks. I dig through my mind to uncover ideas, which only become coherent after a level of experimentation and searching. What I love most about being an artist is that when I find something inside me and externalise it, I’m the first to encounter it.

CM: What drives your choice of medium?

MM: What’s a medium? That’s the first question. A medium is the starting point of a path—but for me, it’s the end. What I’m trying to communicate chooses its medium. My role is to master each medium, so that I can facilitate the expansion of the idea. Take my short film, Pendulum. I wanted to show the complexity of freedom and what comes after emancipation. To uncover that, I used film because of its temporal quality—the sense of time and scale it embodies. The question came first.

CM: We often view abstraction as less tied to reality than figuration, which seeks to emulate it. How can abstraction reveal overlooked elements of our world?

MM: In The End of Figuration, I focused on how we’re misguided in our treatment of abstraction as a parallel to figuration. It doesn’t work like that. Figuration does not truly exist—it’s merely evoking something so real that we believe it is the thing itself, but it is not. Even the process of turning an object into something so real that you identify it is an abstract process—it draws on faith, learned knowledge, ideology. In that way, abstraction is an acceptance of uncertainty, of experiencing life beyond our physical, mental, and spiritual boundaries—it allows you to interrogate assumptions we make about what is neutral representation.

CM: You were raised in Haiti before moving to Canada—places with vastly different relationships to the past. How do you navigate these contrasting influences?

MM: I don’t define myself as part-Haitian and part-Canadian. I grew up in Haiti, but I became a man in Montreal. Both lands carry histories with First Nations. In Haiti, those peoples were completely erased. In Canada, their history is still being written.

I see my work as a way to resist erasure. Even when I don’t feel like I’m succeeding, I know this is what I am here for. I hope my actions contribute to preserving the precious, diverse ways of seeing and being present in Canada and in the world.

CM: What is the role of art in inciting political change?

MM: I’ve used art for many things: personal growth, marking historical moments, sharpening spiritual paths. All of that has fed an elasticity within me: an elasticity with reality and myself, with time and space. It has allowed me to be very close to the world at certain moments, and very far from it at others. It’s impossible to create change without being aware of the present but also holding it at a certain distance—a distance nourished by hope and the dream of a future. I say dream because we must imagine it first, before we can fight for it, before we can even give our lives to it.

CM: How does that bleed into your role in the art world?

MM: I see myself as a citizen, not only an artist. The art world is small, and it can be conservative, so I try to act beyond it. I executive produced the film The fight for Haiti and put together The Marie-Solanges Apollon Programme with AWARE with the goal of giving visibility to women artists from the Black Atlantic, from the nineteenth century to today.

CM: Do you feel institutional resistance to taking such overtly political stances?

MM: I don’t feel that I’m taking overtly political stances. I could do more. But is it about taking a stance, or about doing the work? What matters most at the end of the day? The art world is a very fragile and volatile environment, with very few artists on the boards of institutions. That says something. It’s an environment where an artist can always vanish. Where does the power that creates our cultural legacy really reside?

CM: Do you worry about the precariousness of your role in the art world?

MM: There was a high for Black artists a few years ago, but that’s gone down now—you can see it financially, almost spiritually. In certain contexts, my work can be subversive because it comes with a complexity and certain contradictions that underline serious problems with structures created to sustain diversity.

CM: Given your foray into fragrance, I wonder what Bury Your Masters smell like.

MM: It’s very ground-like, soil-like. I would have to do some samples, because sometimes in the process you discover an element, and it changes the entire formula.

CM: Why was it the right time to create this collection?

MM: The wave of recent global violence underscores a need to move in the direction of a new world. It’s impossible to reach this new world without burying our masters—the forces that are diminishing and erasing our existence. Sometimes the master can be within us—like the patriarchy, classism, or post-colonialism. At other times, they’re external. Either way, they must be reckoned with to truly address contemporary and historical tipping points.

CM: The phrase ‘bury your masters’ also implies a rejection of the artistic canon.

MM: Any process of abstraction is tainted by the visual legacy we’re exposed to. When I learned about Western artists, they became my masters. I learned it was important to kill them. This is how I come to know them better. To kill, in this sense, is not to harm, but to strip them down to their essence within me—to name them, to recognize their presence. Once disarmed, they no longer rule. I can return to them when I choose, not when they demand.

CM: And before we move on, what’s the most exciting piece in the collection?

MM: In the heart of the revolution 2. It combines spirituality, figuration, symbolism, and materials like fabric, tape, paper, paint. I couldn’t find a way to organize the piece so that it felt balanced. There’s also an element of figuration. The boxes with lines started as hands and then turned into cubes—they still function as a short-cut for hands, symbolic stand-ins for the viewer to identify.

CM: In the New York Times, you’re quoted as asking ‘How can we build when we are inhabited by rage?’ Is there an answer to that question?

MM: Rage is guilt for white fragility. It’s the first step toward self-actualisation, which is difficult because it’s easy to get stuck there. The real work begins once we decide to go beyond it: to sit with the rage, let it run through our bones, and then start digging to see what it was hiding. What’s left in us after that? Can it fuel the lessons I need to survive, or will it carry me to my grave? If I scream, who will hear me?

CM: That leads us into the broader politics of today. In the United States and elsewhere, reparations have become a heated topic. What’s your take?

MM: Discussions of reparations have been significant in African countries too. Let’s not make the US the centre of the world. The first question that comes to mind about reparations is: are the countries who feel obliged to face that today truly ready to address the weight of their legacy? I mean, not just theoretically—are they ready to teach the next generations what the foundations of their countries really are?

CM: Does addressing these legacies require a process of us burying our masters?

MM: Yes, which means burying a part of ourselves.

CM: To shift gears a little, what are you currently learning?

MM: When I told my sister about Bury your Masters, she recommended I read The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House by Audre Lorde. I’m digesting that. I’m also learning about the beauty of moving things that touch me at my core and help me connect with others. That’s priceless in my practice.

CM: And finally, what’s next for you?

MM: Everything. I’m thinking a lot about the idea that the body doesn’t end with the skin, but the limits where your eyes lay. I’m looking at the view around me—the sea, the trees—and feel like everything is inside me.

Bury Your Masters by Manuel Mathieu opens at Pilar Corrias on 12 September.