On April 8, 1990, a body washed up on the shore of American television. Wrapped in plastic, face pale against the grey of the Pacific Northwest, her Prom Queen–all-American–good-girl appearance carved space for a question that would echo for decades: Who killed Laura Palmer?

From the shocking image of her lifeless body came the first swelling notes of Angelo Badalamenti’s Twin Peaks theme, guiding viewers into the unsolved mysteries of the town through the eyes of Agent Dale Cooper: “Entering the town of Twin Peaks, five miles south of the Canadian border, twelve miles west of the state line. I’ve never seen so many trees in my life.”

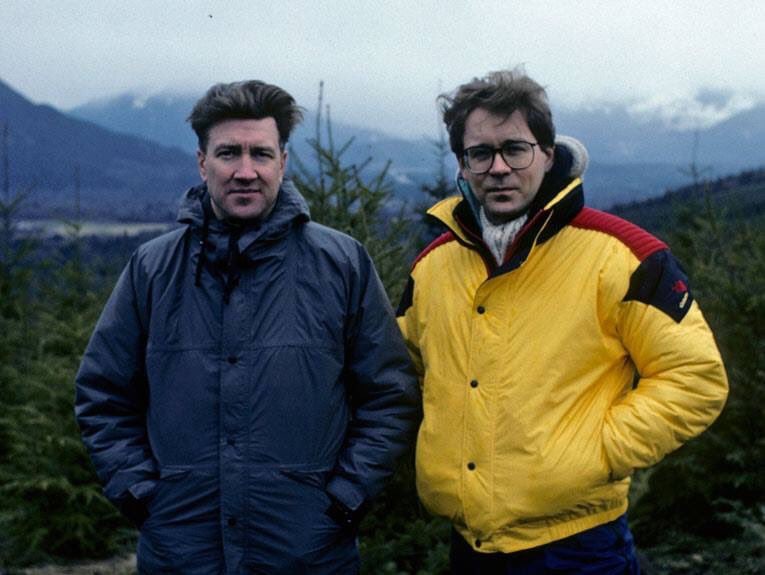

It was Mark Frost, alongside David Lynch, who crafted this uncanny world, where the murder of Laura Palmer revealed the unease beneath small-town America, the secrets that hum beneath diner chatter and pine trees, where “the owls are not what they seem” yet you can still enjoy a “damn fine cup of coffee.” Frost helped invent a new language for television: part soap opera, part psychedelic trip, infused with Western esotericism, secret societies, and mystical traditions.

Thirty-five years later, following Lynch’s passing earlier this year, Frost revisits that world on MUBI’s new podcast Ladies of Lynch. In our conversation, he shared insights on the show’s balance of comedy and dread, his approach to writing women who resist cliché, and the town itself as a living character, where the mundane, the absurd, and the sinister coexist.

When I met with writer and co-creator Mark Frost, I was greeted by a view reminiscent of Agent Cooper’s drive into Twin Peaks, but instead of winding through the trees, the town’s outline peeked through behind Frost’s head, as his Zoom background.

The Cold Magazine [CM]: The podcast begins with you reflecting on a tragedy that lingered with you – the murder of a young girl you knew in 1966, an incredibly traumatic and formulative experience at such a young age, and later your work with David Lynch exploring the mysterious death of another young woman — Marilyn Monroe. From the Twin Peaks pilot in 1989 and its continued success, to today’s fascination with true crime (especially with female audiences), there’s something about these stories of beautiful young dead women that grips the public imagination. Why do you think this is?

Do you think it’s a desire to make sense of the senseless, a morbid curiosity, or something deeper about how we reckon with beauty, loss, and the unknown?

Mark Frost [MF]: There should be a global preoccupation with the violence that is directed toward women from men who seem to be stuck at a kind of primitive caveman level of moral development, who’ve had trouble recognising women as human beings for millennia now. It’s long past time for the human race to get itself together and recognise that we’re all here sharing a planet, and we’re all here, hopefully, to work for the continued future of the species.

I think that kind of violence, the kind of violence we’re seeing with this really sick preoccupation of the Republican Party in this country around paedophilia, when, in fact, it seems most of the culprits all turn out to be Republicans – It’s shocking but it’s an age old story. And we chose that, I guess, as a way of getting into the story of Twin Peaks, as the perfect way to kind of peel back the layers of a town that appeared on the surface to be placid and peaceful and kind of idyllic. In fact, I think once you look under the covers at just about any society, you’re going to see this kind of thing happening.

There was a sort of stealth objective, in a way, with that as our entry into the story. To wake people up to the issue? I wouldn’t say that was our number one intent. The primary intent of any storytelling for wide audiences is to entertain them, but if people also take a moment to consider the moral, ethical, and social implications of this kind of endemic violence, that’s a bonus. I hope the show has contributed to that dialogue in the 35 years since we debuted.

[CM]: That moment in your childhood, was that the crux or catalyst to create Twin Peaks, or did it emerge once you were already in dialogue with David Lynch?

[MF]: I wouldn’t say it immediately jumped to the fore. Once we started exploring the idea of telling the story of this small town, I also had an antecedent in my life: a story I grew up hearing about a murder in 1911 in upstate New York, where the body was discovered in a body of water. That was equally important to me and what initially came to mind.

As we got deeper into the ripple effects, what this does to families, what it does to a community, I could call on my own experience of being close to a tragedy like this. I remember sitting through screenings as we tried to depict the gut-wrenching grief of an event like this, especially in Grace Zabriskie’s performance as Laura’s mother. There was nervous laughter in almost every scene where she was grieving. I don’t know that we would get that now; I think people are more ready to deal with the reality of what this does to people.

As it happened, this became our way into the community, illuminating almost every relationship and character. In many ways, it proved prophetic as a way of entering Twin Peaks.

[CM]: That leads on nicely to my next question. I read a quote by author Judith Guest saying that despite the dark subject matter, Twin Peaks showed that both good and evil can live in tandem, one doesn’t have to cancel out the other.

How did you and David Lynch approach balancing the show’s lighthearted, comedic, or even absurd moments with its darker, surrealist more tragic core? And how did this balance affect your sense of the town itself, as a place where the mundane, the comic, and the sinister coexist?

[MF]: I think that was a reflection of how we perceived everyday life. Each day can be a cavalcade of comedy, tragedy, and the absurd. As you say, one doesn’t cancel the other. They do coexist. It’s the Ying and the Yang of human existence. Evil is a persistent problem in human history; it hasn’t gone away. And when it’s as stark as we’re seeing now, particularly in this country, you realize it hasn’t vanished. To pretend it has is to stick your head in the sand. It’s going to take a collective effort from everyone to get a grip on life and realise it’s here for everyone, it doesn’t belong to any one gender, social class, or economic class. It’s a persistent issue and, in many ways, central to human life. When will we ever get to this alleged golden age where there is equality and opportunity and equity for all people?

[CM]: Do you think that ability to balance light and dark, the warmth and the sinister, the uncanny, along with the depth of your female characters, especially compared with so many other dark series that feel one-note or heavy, is what has helped Twin Peaks endure?

[MF]: Well, I was very fortunate in that I grew up in a family with a long history of very strong women, my grandmothers, great-grandmothers, and my own mother. They didn’t see their lives as impinged by the limitations of the social time they were in. They struck out on their own and tried to do and live as they saw fit. That was a great lesson to learn growing up, because I had those role models in my life.

When it came time to create the population of the town, I wanted to make certain we weren’t neglecting that quality. Most shows, as you say, tend to be one or the other. They tend to be kind of silly, or they tend to be far too single-mindedly dark. And what we always felt was that the light is always there to leaven the darkness. That’s what life felt like to us, and that’s what we tried to write, that in the midst of sadness and tragedy, there will be somebody who slips on a banana peel, figuratively speaking.

[CM]: Or a character like the Log Lady?

[MF]: Yes, I mean, thank God for those moments, otherwise the despair might be too crushing, you know? And the Log Lady’s a great example, because it began as sort of a one-joke character that David had created with Katherine. It was a running joke. But for me, I said “Well no, she’s a kind of mythic tradition from age-old storytelling. She’s a witch in the woods, she’s the shaman, she’s the seer.” And so I wrote her from a very serious standpoint, and I elaborated on a lot of that in the novel I wrote, The Secret History of Twin Peaks. I tell her whole story, and I think that’s a great example. It seems like a joke on the surface, but as people were drawn in, they realised, no, Margaret was perhaps the most formidable person in the entire town.

[CM]: It’s interesting, because the way you describe the Log Lady, as a kind of seer or figure of ancient wisdom, feels connected to the esoteric layers that run through Twin Peaks and The Secret History. I wanted to ask about your interest in esotericism and these kinds of philosophies, and how they informed your storytelling.

[MF]: I’ve always been drawn to alternate ways of looking at the world. I was trained as a drama student, I was grounded in the Greeks and in Shakespeare, those classic traditions of mythic storytelling. So I felt that I wanted to bring all of that into this world, that there’s no one way of seeing or perceiving or living life. There are a myriad of ways. Everyone’s different, and everyone’s going to be drawn to a mythology that appeals to them.

So I was trying to create a kind of alchemical mix of all these ideas, that the supernatural and the natural often overlap or intertwine. And as I talk to most people in life, if they have an imagination, that’s how they perceive life too: ‘There’s more on Heaven and Earth than is dreamt of in your philosophy, Horatio.’

This is a very mysterious place we find ourselves in, and I wanted to bring that to the forefront of the storytelling.

[CM]: That really comes through, even watching Twin Peaks now, it feels rooted in those ancient traditions. I actually saw The Bacchae at the National Theatre the other night, and there are moments in that play, the frenzy, the possession, that echo those scenes of Laura Palmer in the Red Room. That sense of being overtaken by some larger presence

[MF]: It’s Medea. It’s Cassandra. You know, with all those characters from myth, all those things live in us, I think, as almost a kind of aspect of our DNA. And we neglect them at our peril.

[CM]: That idea of ancient archetypes living within us made me think about the mythology of doubles in Twin Peaks. I was reading about Germanic folklore recently, and it said that if someone sees a double, it represents the promise of death. That always reminded me of Maddy, the way she appears as a kind of doppelgänger of Laura Palmer. What did you intend her presence to represent narratively, as she lingers after Laura’s death – and the fact that her own death isn’t mourned in quite the same way?

[MF]: Well, number one, it came from a very practical idea, which was that we had so admired what Sheryl Lee was able to do with the character in the very small ways we saw her in the pilot. As you probably know, we first found Sheryl from a photograph, she was dressed as a homecoming queen, and we just thought, that’s Laura. We knew instantly. And when we met her, we were utterly charmed by her. She’s a wonderful person.

So for me, it was a way to get Sheryl back into the show. That was the original intent. Then I started to think about the doppelgänger mythologies and what that would mean. Vertigo came to mind, which is a haunting exploration of the same ideas. And it did seem that, given what had happened to Laura, she was kind of doomed from the start. It did hearken back to that doppelgänger feeling in the story, that uncanny doubling, and it ends sadly for her as well.

[CM]: That idea of the double, the hidden self, ties into the Jungian and esoteric themes that run through your work. I read that W.B. Yeats was an influence; was that connected to your interest in mysticism and the occult?

[MF]: Well, I mean, this is kind of my métier. I studied all these things. Yeats was a mystic, and I think he was associated with the Order of the Golden Dawn. So I knew all about that from reading about the Irish playwrights. I’ve got both Irish and British blood. Believe it or not, I’m descended from the Plantagenets. I try to bring as much of that back into my storytelling as I can.

Mark Frost’s conversation is part of MUBI’s Podcast Season 9: Ladies of Lynch, hosted by Simran Hans and available now on Spotify. The season also features Isabella Rossellini, Jennifer Lynch, Sabrina Sutherland, and Deborah Levy discussing the women at the heart of David Lynch’s work.