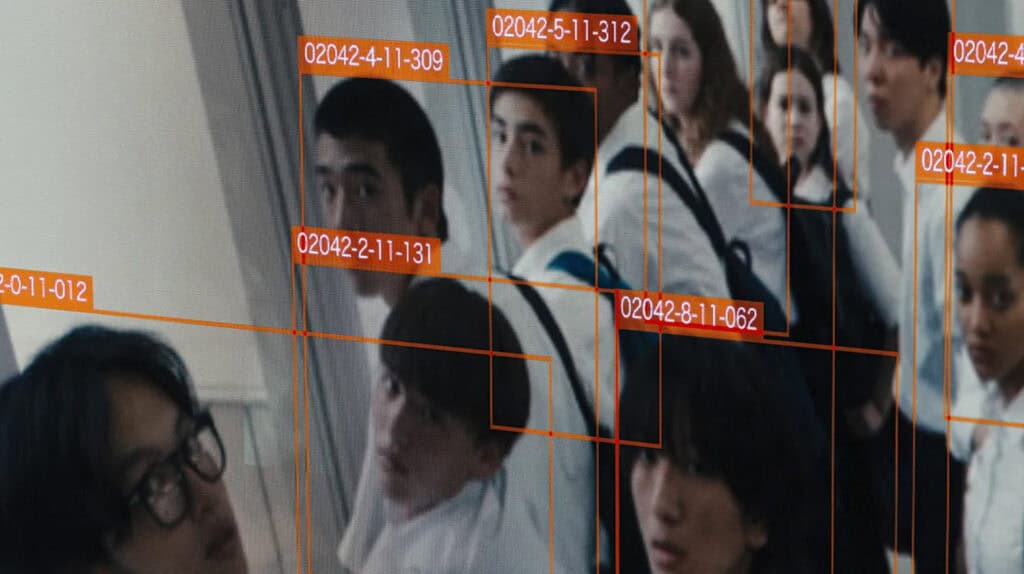

Set in a near-future Tokyo, Happyend follows Kou, a teenager sneaking into raves with his group of best friends, trying his best to graduate, and following the lead of the daring Yuta. But the looming threat of an earthquake has tightened the government’s hold over the city, and an increasingly oppressive political climate is seeping into school life. When facial recognition software arrives on campus, the teens are forced to confront the creeping shadow of fascism and their own uncertain place in the world.

Political awareness doesn’t look the same for every teenager. Kou – of Korean descent but born and raised in Japan – remains un-naturalised, his life shaped by persistent exclusion. His attempts to communicate that frustration, especially to the carefree Yuta, never fully translate. As their classmate Fumi galvanises a tide of student unrest, the bonds between Kou and Yuta inevitably begin to fray.

Neo Sora’s latest film has been in the works for years, but its release couldn’t be more timely. Alarm bells are ringing in the heads of young people all over the world, over climate collapse, the vertiginous rise of nationalism, and the violent policing of dissent. What to do in the face of all this crisis? Happyend offers some deeply personal, poignant answers – a portrait of personal revolution and political awakening. But it’s also a film about friendship, about how people come together and fall apart, and how all of that is okay.

The Cold Magazine (CM): Could you tell me about the inspiration behind the film?

Neo Sora (NS): I’d say the most important emotional thrust came from my own upbringing, and from the emotions I was feeling in my early twenties. A big part of that was how much I value friendship in my life, and how central it’s always been for me. At the same time, because of political differences and my own political awakening, I ended up drifting away or being cut off from some friends.

At university, I started to deepen my understanding not only of how society works, but also of Japan’s history of imperialism and colonialism. That’s what eventually led me to study the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, which devastated the Tokyo region. At the time, Japan had colonised Korea, and many Koreans were brought into Japan as forced labourers. The disaster ignited deep-seated colonial resentments and fears. Rumours began to spread – that Koreans were poisoning wells, stealing, or even killing Japanese people. None of it was true, but the media, the government, and the police fuelled this demagoguery, and it led to the massacre of more than 6,000 Koreans.

Around 2014, I was seeing disturbing echoes of that history in Japan. There were hate-speech rallies organised by right-wing groups, with ordinary Japanese citizens shouting horrific slogans against Koreans, Chinese people, and other foreigners. It struck me that if another earthquake of that scale were to hit, what would stop another massacre, or even a genocide, from happening? That thought experiment, combined with my own personal experience of losing friends over political differences, really became the seed of this film.

CM: Why did you decide to portray this growing authoritarianism within a high school and through a high school friendship group?

NS: I was reflecting on myself as a student, and part of the impetus behind the film was to capture that free-spirited, “ignorance is bliss” feeling of being in high school. But of course, that’s a lie. For some people, especially those without privilege, the things you might be able to ignore tend to seep into your life. I also think that high school is a time when – even if you don’t have the words to articulate it – you start to feel this frustration or anger about large societal problems. You may not know exactly how to express it, but you do feel it. High school is when you begin learning how to put those feelings into words, but that process can be really frustrating.

That was definitely true for me, too, back when I was in high school. My best friend was someone I’d known since elementary school. And when you’ve spent that much time with someone, you expect them to just understand everything about you. So when they don’t – which of course they won’t, because they’re their own person – it can feel like a kind of betrayal. It’s this illusion, right? That they should understand you completely. And when they don’t, that can be incredibly frustrating.

CM: The film pays close attention to how privilege operates, particularly in terms of race and naturalisation status. Could you talk about how you approached writing those themes and what guided their inclusion in the film?

NS: I think there’s a certain amount of imaginative labor that people without privilege have to do in society. So, for example, if you’re of foreign descent or have roots in another country, but you were born and raised in Japan, you still understand exactly how you’re expected to act. You know what Japanese people expect of you, and you can imagine their perceptions of you. But that imaginative labour isn’t reciprocal. A so-called “normal” Japanese person won’t necessarily have the same capacity or need to imagine all the roots and cultural histories that someone like Tomu’s character [who is Black] carries. They might not consider what it actually feels like to be Black in Japan, or what kind of upbringing or cultural contexts shaped Tomu’s life. So, privilege creates this immediate asymmetry in how people relate to and understand one another.

That imbalance really comes into play when someone like Yuta says to Kou, “we’re the same.” For Kou, that’s deeply frustrating, because he knows that’s not true. Kou has to navigate specific bureaucracies in order to maintain his special permanent residency status, which is essentially a colonial residue. He has to renew that status every few years just to stay in Japan. If he doesn’t, he’d need to get a Korean passport, despite never having lived in Korea or having any real connection to it at this point. These are the kinds of things that someone like Yuta, who’s never had to think about or experience them, simply doesn’t see. And that creates a huge imbalance in their relationship.

Privilege shapes how we perceive others and how deeply we can understand why people behave the way they do. For Kou, he doesn’t have the luxury of being neutral. When society is moving toward creeping authoritarianism or xenophobia, his choices become very stark: either be victimised by it, assimilate into Japanese norms, or resist and push back. Those options are laid out clearly in front of him. But if you have privilege in Japan, you may never even have to think about making that kind of choice. So, all of that – the constant labour, the imbalance, the lack of understanding – builds up and becomes really frustrating for someone like Kou.

CM: I wanted to ask you about the through-line of techno music and rave equipment and their inclusion in the film. Could you tell me more about that?

NS: One of the first images I had, way before I even considered making a feature film, was of two people carrying a subwoofer through the darkened streets of Japan. That image came from my own experience in university. When I was setting up shows, I’d have to take the subwoofer out of storage and bring it to the venue, and you couldn’t do it alone, you needed two people. It’s physically difficult, but I found something really powerful in that image – this shared labour, this connection. And when I started thinking about the film’s themes, especially around earthquakes, techno music just felt like a natural fit. I think it’s partly because of the vibrations, you feel techno.

Even now, whenever I go to a club or a techno show, I always like to be right next to the subwoofer. I love the feeling of those thunderous basslines and kick drums coursing through my body. There’s something very grounding and physical about it. So, for me, that vibration is both comforting and ominous. Especially in Japan, where the threat of a real earthquake is always present, shaking can be a source of deep anxiety. So I was really interested in how those ideas, comfort and dread, can coexist in the same physical sensation. Techno became a kind of metaphorical bridge between those feelings. And also, I just love techno. That’s probably the simplest answer. But I do think the themes and the music resonated with each other in a way that felt right for the film.

CM: The film’s romantic and playful moments run alongside its political urgency and feel so sensitively handled. How did you approach writing those elements, and what guided your decision to include them?

NS: Romance was a really important reference point in making this film. I really do see Happyend as a love triangle movie – where it’s Fumi and Yuta fighting over Kou. But the thing is, the form of that relationship isn’t a romantic or sexual one, it’s about friendship. And for me, that kind of deep understanding between people is romantic, in a way. Just not in the conventional sense.

I’m really interested in friendship because, unlike romance or family, there aren’t social rules around it, it can take any form. For some people, a friendship might be the deepest relationship they have, deeper than with a spouse or a family member. And for others, it might be something casual, like someone you get drinks with or talk about music with at a bar.

But if your best friend is the most important person in your life, there’s no recognition of that, and that’s always felt strange to me. Why is it only marriage that’s celebrated or validated in society, especially when we know, say, in the U.S., that more than 50 per cent of marriages end in divorce? Meanwhile, many people have friendships that last their whole lives. So, I was thinking a lot about that when writing the film. I wanted to borrow the structure of a traditional romantic triangle, but apply it to friendship instead. I shot it like a romance film, but the emotional stakes are in the friendship dynamics. That’s where the real intimacy is.

CM: I wanted to ask about the broader atmosphere of the film – it really resonated with global concerns over climate anxiety, protest suppression, and the rise of techno-fascism. I’m curious what it’s been like for you to see the film roll out, first in Japan and then internationally, and to witness how those themes have connected with audiences around the world.

NS: Funnily enough, I think the film actually resonated more outside of Japan than it did within. Even though a lot of the things I was imagining or predicting for Japan are starting to happen now. For example, there’s the upcoming Osaka Expo, and in preparation for it, I saw that the train system is starting to implement facial recognition payment systems. That kind of surveillance infrastructure is becoming very real.

At the same time, there’s been a rise in far-right populism in Japan, just like we’re seeing in so many other places around the world. The film didn’t perform as strongly in Japan compared to places like Hong Kong and South Korea. And I think the biggest factor was whether a country had recently experienced a mass student movement. In Japan, that kind of student-led mobilisation hasn’t happened in years. But in Hong Kong there was the pro-democracy movement just a few years ago. And in [South] Korea, this past December and January, there was a major protest movement in response to President Yoon’s actions – which, interestingly, mirrored exactly what the Prime Minister does in my film: using an emergency decree to try to stay in power.

In Korea, something really clicked. The film became very popular there, but that popularity is bittersweet. On the one hand, I’m grateful that the film resonates so deeply with people. On the other hand, the fact that it does resonate means they’re living through the very systems the film is critiquing. So in a way, the more successful the film is, the more it confirms how bad things are. At the same time, there have been moments that truly moved me.

In Korea, one audience member told me that during a sit-in protest in front of the presidential palace this past winter, someone came up and gave them a kimbap [a popular Korean rice dish, similar to sushi] because they had been out there for so long. So when they watched the final scene in the film, where the students occupy the principal’s office, that moment hit them in a really personal way. To hear that someone who is literally out on the streets fighting for what they believe in felt seen by the film – that means a lot to me. That’s the kind of connection that makes all of this worth it.

CM: Is there any message you hope this film gives to young people watching it today?

NS: I usually prefer not to specify any kind of message, because I really believe that a film belongs to its audience. That said, there was something I had in mind while making the film. If watching it makes someone want to pick up the phone and call a friend they haven’t spoken to in a long time, then I would consider that a success. I really believe that reconnecting with people, especially friends you may have drifted apart from due to political differences, is a powerful step. It can help us begin to understand why those differences emerged, both between individuals and within society more broadly.

Just to be clear, I’m not saying we need to excuse or forgive fascist attitudes or anything like that. But I do think there’s often fear at the root of those beliefs. People are scared – about the future, about the environment collapsing, about shrinking resources. That fear can make people vulnerable to narratives that scapegoat others, telling you it’s “that group” or “those people” who are the problem.

But more often than not, the real issue is structural: it’s about class, or power imbalances in society. So, I think one way to begin pushing back against those narratives is simply by continuing to talk to people. To have conversations, not just with strangers on the internet, but with the people already close to you. I know that’s not always easy, but that kind of dialogue is one of the first steps. So, if the film inspires someone to reach out to a friend they’ve lost touch with, that would make me really happy. But again, there’s no single message in the film – people should take from it whatever resonates most with them.