How do you uphold your reputation as New-York’s nightlife aficionado, perfect the Dewey Decimal System, and seduce the handsome owner of your local Lebanese food truck – in a daily ritual of asking him for “a falafel with hot sauce, a side order of Baba Ghanoush and a seltzer, please?” – while donning a designer wardrobe of late 80’s couture? Truthfully, I don’t know. But, 30 years on from its original release date, Daisy Von Scheler Mayer’s Party Girl gets us pretty close to the answer.

There’s few films that explore the nuances of youth culture quite like Mayer’s 1995 cult-classic. Which, thanks to Gen-Z’s rediscovery of indie-queen Parker Posey, has found renewed resonance with a contemporary audience. Three decades on, the film manages to transcend generations in its profound exploration of early adulthood and the optimistic nihilism that comes with it; speaking to a new cohort of twenty-something year olds caught between the desire to fulfill their career aspirations and the hedonistic pursuits of ‘the good life’.

At the centre of Party Girl we have Mary – played by Posey – as the eccentric yet epicurean queen of the New York club-kids turned librarian. In the film’s opening scene, we’re thrown straight into the discomforting chaos that defines our protagonist’s lifestyle; meeting her in a characteristically New-York stairwell, surrounded by a tornado of characteristically New-York acquaintances, as well as her short-paid roommate DJ (Guillermo Diaz) and the odious cops that have come to crash her party.

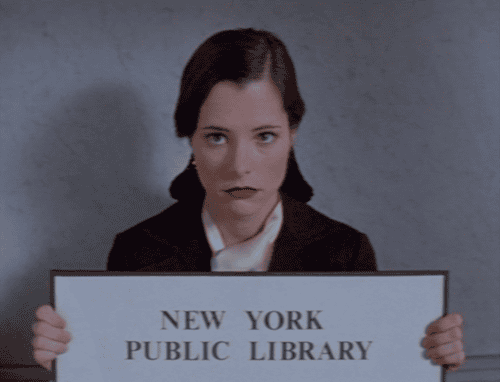

The penny drops when Mary is forced to do something that no brimming socialite in her mid-twenties wants to do: get a job. It’s Judy – played by former party girl and Mayer’s mother Sacha von Scheler – her fairy-godmother, actual godmother and head librarian at the New York library, who employs her. Motivated by her need to impress Mustafa, the intelligent and good-looking owner of a Middle-Eastern food van on her block, Mary changes her ways and, after throwing a distasteful party and taking a “powerful, mind-altering substance” intended to make her “unborn children grow gills”, vows to live her life for others.

In Party Girl, there really is no Maid Marian without Parker Posey, who Mayer herself said possesses an “undeniable sparkle dust” in the film. More recently, we’ve come to know Posey for her role as the benzo-addicted, geographically challenged Victoria ‘You can’t move to Taiwan!’ Ratliff, in season three of The White Lotus. A woman who would rather die than live without her disconcerting collection of luxuries.

Mayer owes Posey’s “sparkle” to her own, Mary-like brazen-ness. In an interview with Jezabell she said “sometimes Parker and I would butt heads, because I wanted things word-perfect and she wanted to add a like, ‘T-O apostrophe Up: Toe up!’ and I’m like, ‘What are you even saying?’ I think that even that tension creatively between the two of us was awesome. And obviously we love each other now.”

Mary belongs to that category of ‘un-likeable’ yet undeniably charismatic women we’ve seen in cinema since it began. Her vulnerability transcends generations, making the viewer, as writer Katie Driscoll puts it, “resonate with the universal trappings of early adulthood” 30 years on. She’s the Edie Sedwig of the 90s; with the same flighty disposition as that of Hollie Golightly, the self-centredness of Jean Harringdon and the unwavering assuredness of Hannah Horvath. We like her because we are her and, like her, feel pulled between these alternating dimensions of professionalism and a life of carefree indulgence.

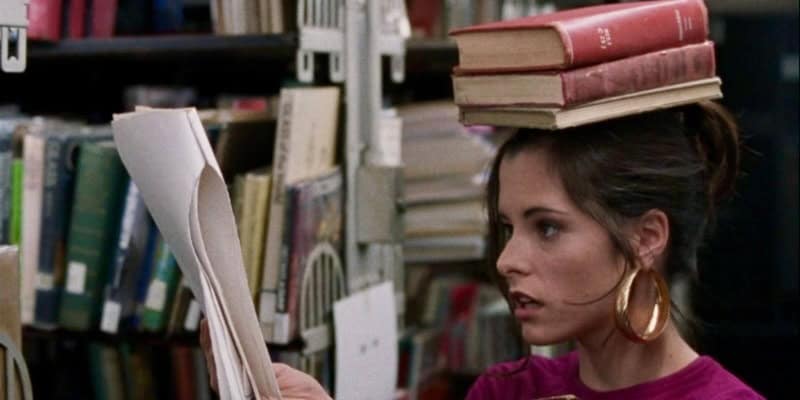

Party Girl’s true charm lies in its ability to dance between two very different spaces; New York’s underground club scene and the library. When the film was released in 1995, it was the first of its kind to do so on the internet, setting its president as non-conforming cult-cinema and an authentic exploration of these spaces by the people within them. “Showing that scene on film wasn’t part of our agenda,” said Mayer, in an interview for Vogue. “But it was how we lived, and it was nice for it to be accurately depicted for once. I did my share of gay clubbing, but [my co-writer] Harry (Birckmayer) knew the scene better than me, as did Bill Coleman, who did the music,” she said.

If you have a keen eye and a familiarity with 90’s LGBTQ+ party culture, Party Girl’s club scenes second as a game of spot-the-cameo. Whether it’s Mary joining “Nah-tah-sha”, que Natasha Twist, to vogue on the dance floor or the It Twins with green hair, you’re met with “real nightlife characters,” said Mayer. “We were so excited to have them. It was big to get Natasha, and of course Lady Bunny who we did know and Harry was friends with,” she said.

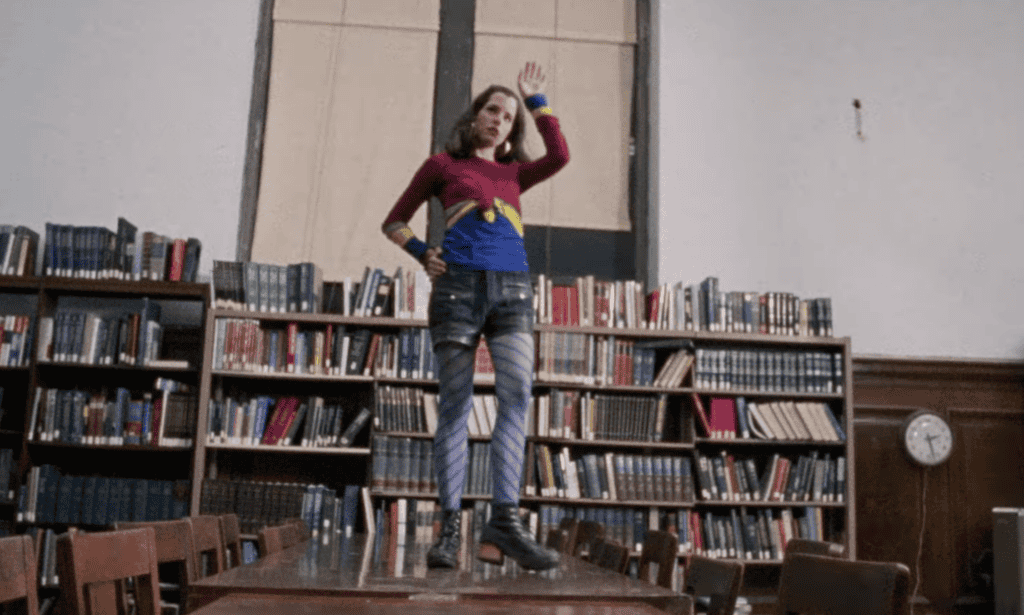

At the centre of this whirlwind of club-kids, party promoters and DJ’s is Mary’s wardrobe. Whether it’s the blue satin gloves she wears when arguing with her non-boyfriend-boyfriend bouncer, the leopard print coat we see her in after being bailed out of jail or, and perhaps most notably, her extensive collection of brightly-coloured patterned tights: New York’s downtown scene was something that fed the vision of Michael Clancey, the film’s costume designer. “I knew the person that Parker Posey was playing, I knew the person that Guillermo Díaz was playing. I knew all of these people. They were my friends,” he said in an interview for Vogue.

We see Westwood, Gaultier and Comme des Garçons paired with thrift-store bought bags, gloves and hotpants. The clothes are just as authentic as everything else in the film, they’re an extension of Mary with their own, unique practical function. What’s supposed to be worn on the runway is instead worn to organise her roommates record collection or dance around a library. “It wasn’t regimented in the way that other costuming I’ve done has been, where it’s very strategic or based on a specific color palette. We just threw things together that seemed to work. We’d come up with our own versions of those high fashion looks we couldn’t afford and combine them with vintage clothes, or something we’d bought from Century 21. That’s how the film was costumed. We had no money,” he said.

Party Girl re-affirms the interconnectedness of these worlds and the complexity of the female experience, while defying stereotypes of early-womanhood. There’s a feminist rhetoric built into the DNA of the film, something that remains unspoken until and apart from a speech by Judy towards its end. Judy talks about the public’s dismissal of librarianism and criticises Melville Dewey himself for hiring women into the role, on the assumption they have “no intelligence”. According to her, they are underpaid and undervalued despite their contribution to society. This speech isn’t just a statement about the importance of librarianship, but Mayer’s way of negotiating our expectations of ourselves.

Yes, Mary is a ‘party girl’ but she is also an intellectual, a librarian! It’s one of the only concepts of the film that has, thankfully, aged over the last three decades, but is a message that still retains its potency all these years on.