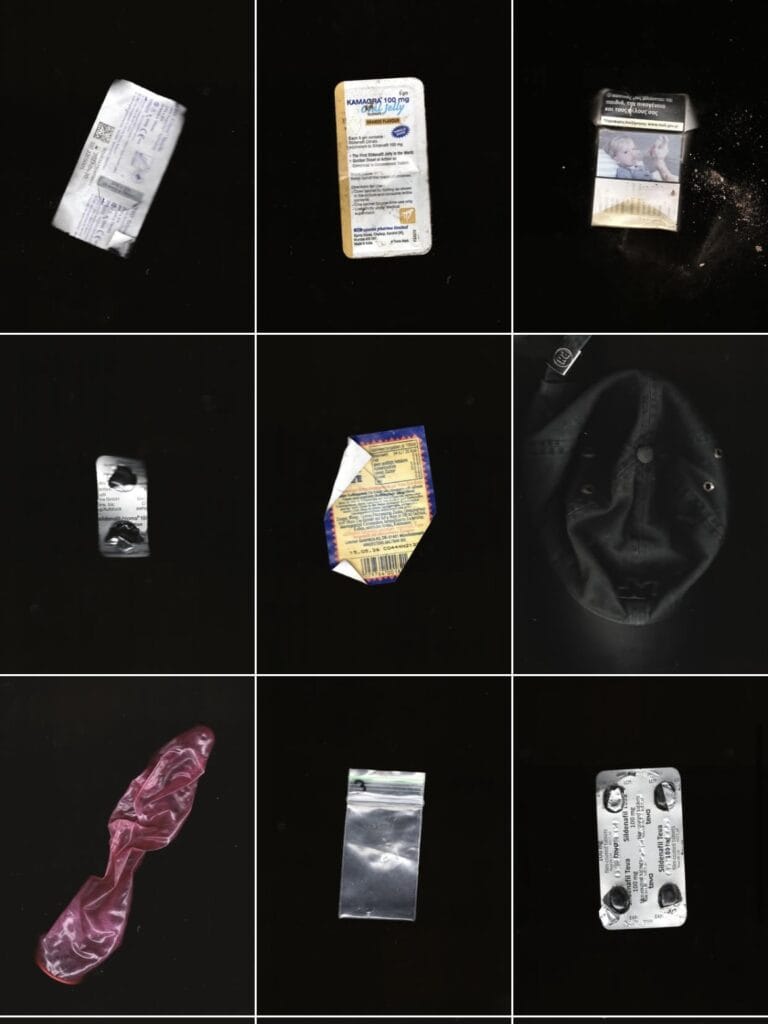

A scattering of found objects lies against the black background of an at‑home scanner. A used latex condom found in Berlin’s Hasenheide, a muddied pair of Aussie Bum underwear from Dublin, and a canister of Iron Fist poppers from London’s Walthamstow Marshes. These relics of cruising culture — that is, the practice of searching for anonymous sex in public spaces — form the visual language of Cruising Archaeology.

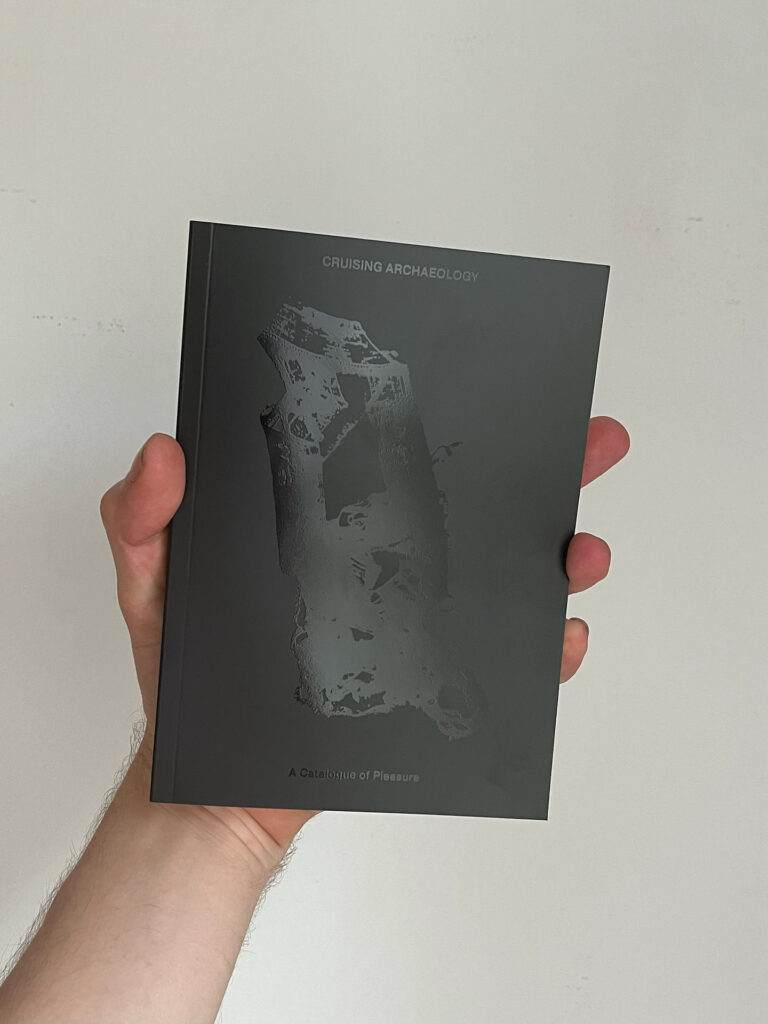

Founded by Jack Scollard of SMUT PRESS, the project began as an anonymous Instagram page before morphing into something between a zine and high-end art book. Accompanied by almost clinical descriptions, it catalogues the remnants of sexual encounters in parks, dark rooms, and highways across Europe. For the viewer, the past lives of these objects remain unknown. Questions of their original use, their owners, or anything beyond where they were found remain unanswered. The stories they do tell, however, are more interesting. They stand as a testament to the fleeting intimacies that have long defined queer life.

And cruising is certainly a part of that story. From Tom of Finland’s steamy illustrations to Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance; Troye Sivan’s “Rush”; and George Michael’s infamous arrest in Beverly Hills, the practice is an integral part of how queer people relate. Today, it’s often mediated through apps like Grindr — but in-the-moment cruising endures, rooted in the same legacy of desire, risk, and resistance. “It’s a part of a whole lineage,” says Scollard.

In our contemporary cultural climate, memorialising these practices takes on even more meaning. With queer sexuality increasingly vilified in our conservative media landscape, Cruising Archaeology is an assertion of unencumbered queer desire. As restrictions on the community become more commonplace, it’s an avowal of the fact that queer people have always sought connection — from London to Berlin, Scollard’s clear that this is not about to change.

What’s more? Scollard’s academic framing forces us to take the practice seriously. At one point, they tell me that this is archaeology. And — as they say in their talk for the University of London — the project explores cruising as a challenge to accepted ways of relating, a rejection of the hegemonic structures that sideline stories of resistance, sexuality, and love. And they are right. Why should objects that so intimately reveal queer legacies be relegated to outside of ‘serious discussion’? What can we learn by centering their stories?

In the lead-up to an appearance at the Athens Art Book Fair, I spoke with Scollard about representations of public sex, the importance of an academic framing, the project’s highly-anticipated second edition, and whether cruising is still radical in the age of Grindr.

The Torn-Off Waistband of Some Calvin Kleins

The Cold Magazine (CM): How did SMUT PRESS start?

Cruising Archaeology (CA): I founded it with my friend Jordan Hearns. We were both studying art in Dublin and during COVID, we put together a zine memorialising nightlife. It sold out immediately. When we moved to London, we set up a printing press with the aim of spotlighting emerging queer artists and producing one-off art books — anything smart, sexy, and provocative.

CM: I saw you did a rave, too.

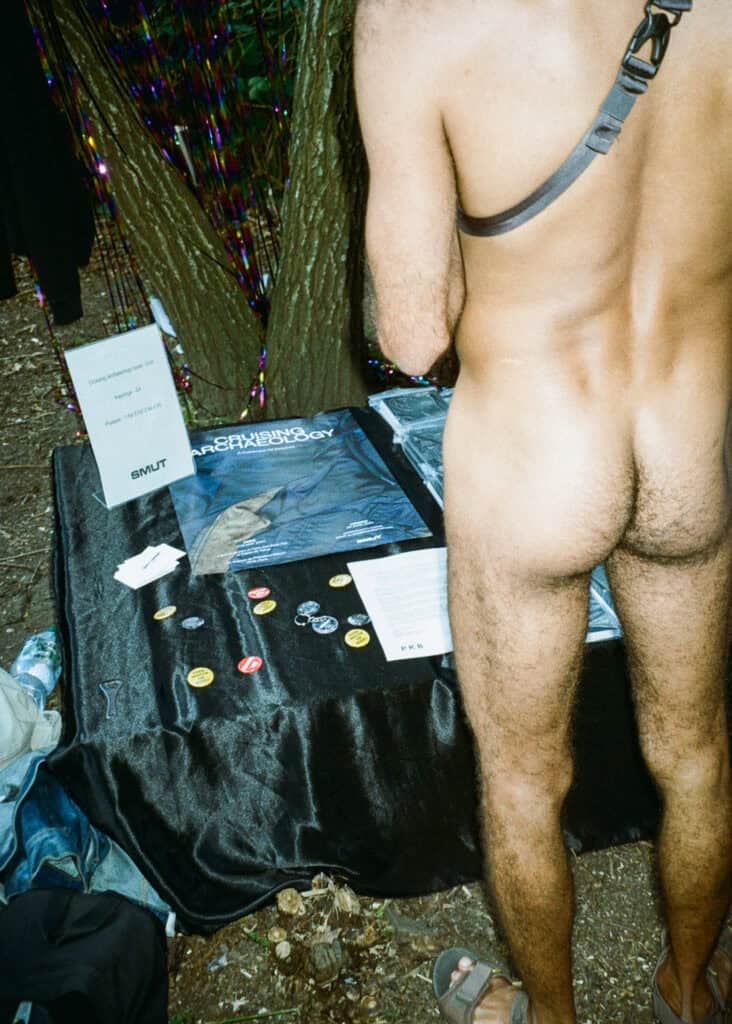

CA: Yeah, we did a rave. We do parties every three months now. They’re a good way to build an audience because books are usually slower-burning than in-person events.

CM: And then, with SMUT Press going on in the background, you created Cruising Archaeology as an anonymous Instagram account. Can you tell me about its origins?

CA: The summer before last, I was spending a lot of time in Walthamstow Marshes, and I found it funny to collect, scan, and post some of the litter. I remember finding the torn-off waistband of some Calvin Kleins. When I posted the photographs, I wasn’t editing them, and the captions were minimal, almost scientific. When the page gained traction, a book made sense. It was the biggest print run we’d ever done, and it sold out within months. Cruising Archaeology launch party, photography by Dani d’Ingeo.

Is Cruising Still Radical?

CM: What do the objects you find say about the spaces you find them in?

CA: Sometimes, the objects allow you to draw conclusions about the profile of a particular place. Areas with older populations often have more condom wrappers, which may mean people use fewer condoms in younger cruising areas, where they’re more likely to be on PrEP.

CM: And what do these objects say about queer desire and cruising more generally?

CA: Though sex is now available online with apps like Grindr and Sniffies, the fact that there are so many objects in these spaces means that cruising still exists on a large scale. Historically, cruising acted as a refuge. It was for people who couldn’t be out, and it was often the only place where they could meet others like them. Now, it’s more about resistance. It’s more of a choice. Take This Is My Culture’s George Michael party at Hampstead Heath. It stemmed from a particular radical politics about being in public space and not being afraid.

CM: How much does that idea of resistance play into today’s cruising culture?

CA: There’s an assumption that cruising is part of a utopian social model grounded in a radical openness to strangers. This is true to some extent. That openness is a helpful skill. But there are also less idealistic behaviors— issues around consent, risks involved. Photography by Dani d’Ingeo.

Cruising Archeology and the Public

CM: How has Cruising Archaeology opened conversations about cruising?

CA: There have been numerous art projects focused on cruising and they’re almost always a photo of two guys butt-naked in the trees. They’re almost always taken from a distance. They’re meant to be so beautiful and fierce, but they’re usually from an outsider perspective. It makes you wonder, what is the relationship between the photographer and these people? I find it more interesting to take away the body and to focus on traces of their intimacy.

CM: What do you offer that these other representations may not?

CA: It’s more about the objects themselves, which offers room for a wider variety of interpretations. There’s an overrepresentation of gay male voices in portrayals of cruising.

What’s interesting about this project is that you don’t know the identity of who used the objects. In Epping Forest, I found a testosterone gel packet. I’m not entirely sure, but maybe they belonged to a trans person. It widens the range of stories you can imagine.

CM: Do you worry about how these objects are being perceived?

CA: I don’t have any control over how the images are perceived. The account is public. What’s to say someone doesn’t see the scans of the needles and point to them as a way of showing depraved the sex that queer people have in these spaces is? But, if I censor the objects based on how they could be misconstrued, that would undermine the goal of creating a real archive.

CM: It’s interesting you’ve chosen processes and languages associated with archaeology.

CA: Rather than trying to illustrate everything, what has been more compelling has been to let people construct things themselves, to take the narrator out of the process. By co-opting a serious academic term like ‘archaeology’, it was also meant to provoke an expanded idea of what the field looks like. There’s a museum in Amsterdam that’s exhibiting a condom from the 1900s, but it’s the only institution to do this. Why are these objects outside the canon?

CM: But this is archaeology.

CA: Essentially, but instead of being a professional in a uniform with all the tools and skills that are needed to correctly excavate historical goods, I am just going around with a plastic shopping bag and some gloves and picking stuff out of the ground.

From Instagram to Print

CM: What’s the difference between posting on Instagram and curating a book?

CA: Instagram is live and I’m constantly adding to it. For the book, I had to make a tighter selection. People don’t read on Instagram either, so the book has the advantage of featuring some solid pieces of writing. That said, it’s easier to build an audience on Instagram.

CM: Do you find the book is better at opening conversations?

CA: Maybe you’re shocked by some of the initial images on Instagram and then you dig a bit deeper, and you buy the book, and you read the interviews, and you engage on another level.

CM: And I hear you’re working on another. Do you want to tell me about that?

CA: It expands on the previous edition. While the first book was just in London, I’ve been creating an archive from different European cities. There’s also a lot of writing. A piece from Joao Florencio in Berlin, who writes about sexual subcultures. Another from Stav B, who wrote about lesbian cruising. The last two pieces are interviews: one with Mati Klitgard, who founded the Gay Consent.Lab in Berlin, and the other with Marc Svensson from You Are Loved in London.

Visit Cruising Archaeology at the Athens Art Book Fair, 3 to 5 October 2025. Information here.