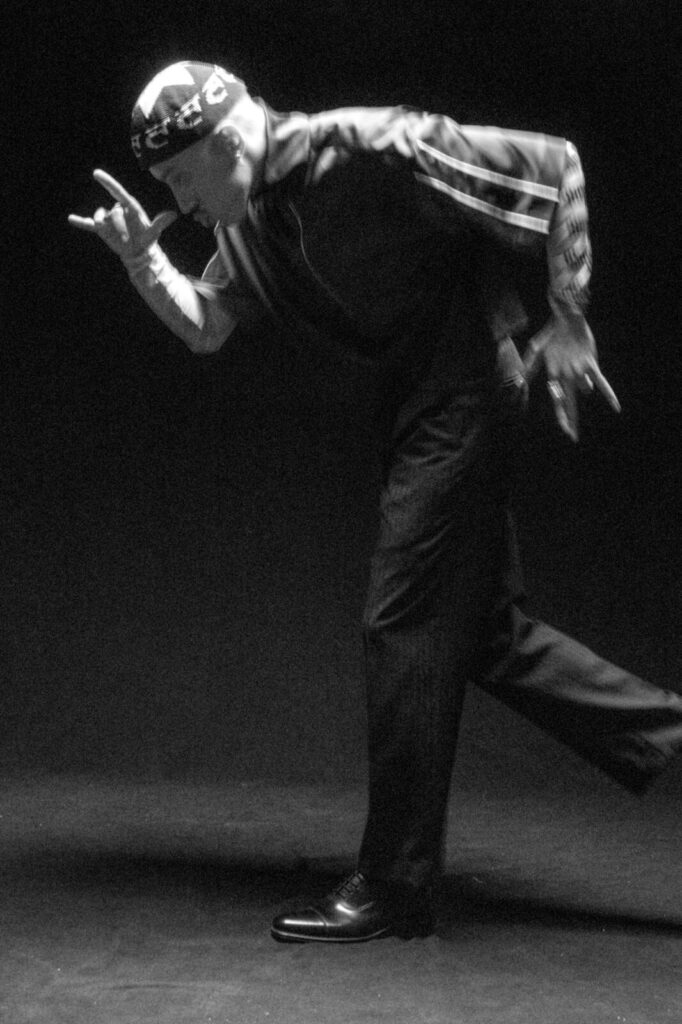

In the last few years, Brazilian dance music has become one of global music’s hottest commodities – from the bailes of São Paulo to crowded London Fashion Week afterparties – and RHR one of the movement’s hottest talents. With an explosive Boiler Room set and Skrillex sessions under his belt, his performances melt funk, dancehall, techno, rap and pop into a euphoric – and distinctly Brazilian – ocean of rhythm, sweat and swagger.

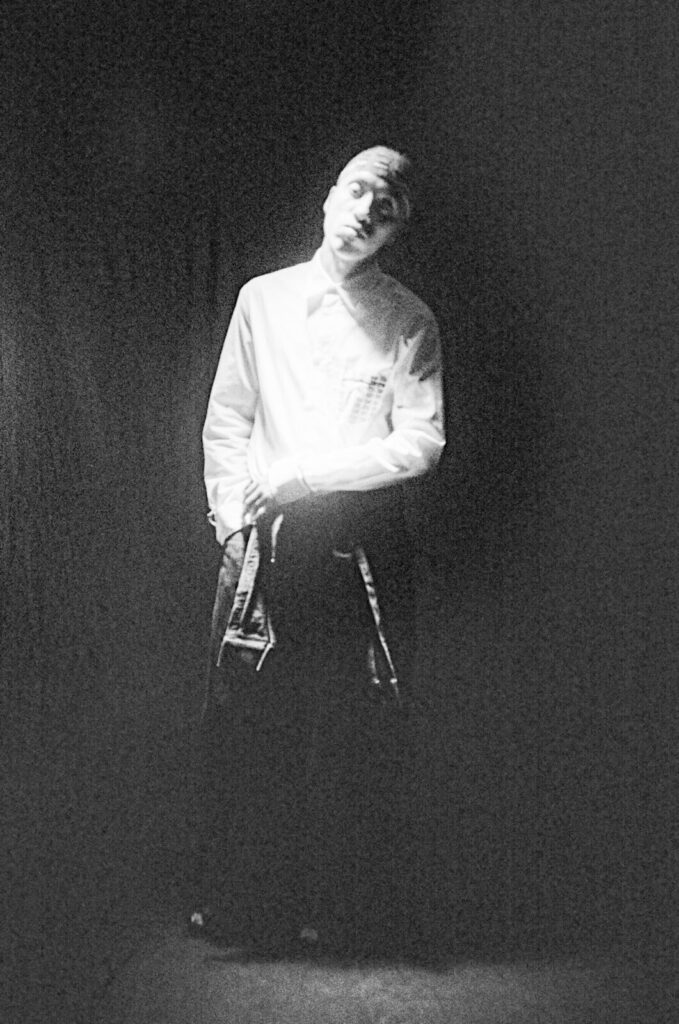

Releasing a new EP in January, The Cold Magazine caught up with the Brazilian DJ to discuss the new project, the philosophy behind his hedonistic sound and the politics of Brazilian dance.

The Cold Magazine (CM): Your upcoming EP is called Gíria. How would you translate the expression into English?

RHR: In Brazilian Portuguese, gíria means a slang word or expression – a term that gains a new meaning within a specific group. It’s a form of language created collectively, almost like an internal code. Slang emerges in communities, peripheral spaces, or cultural groups, and it carries identity, belonging and a distinct way of reading the world. Sometimes a gíria can even be invented by one person and understood only by whoever they choose to share it with.

I chose this name because gíria is fundamentally about creating meaning. It’s about reshaping language and giving new significance to words, in the same way we seek meaning in life, in symbols, and in the experiences we return to again and again.

CM: Does the name have any other significance?

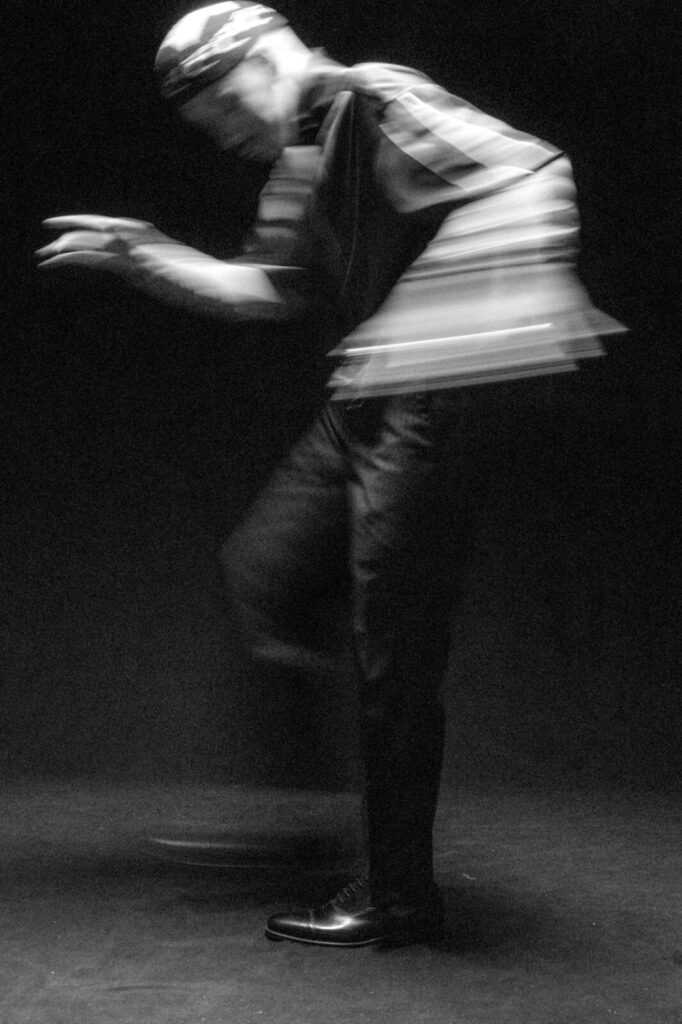

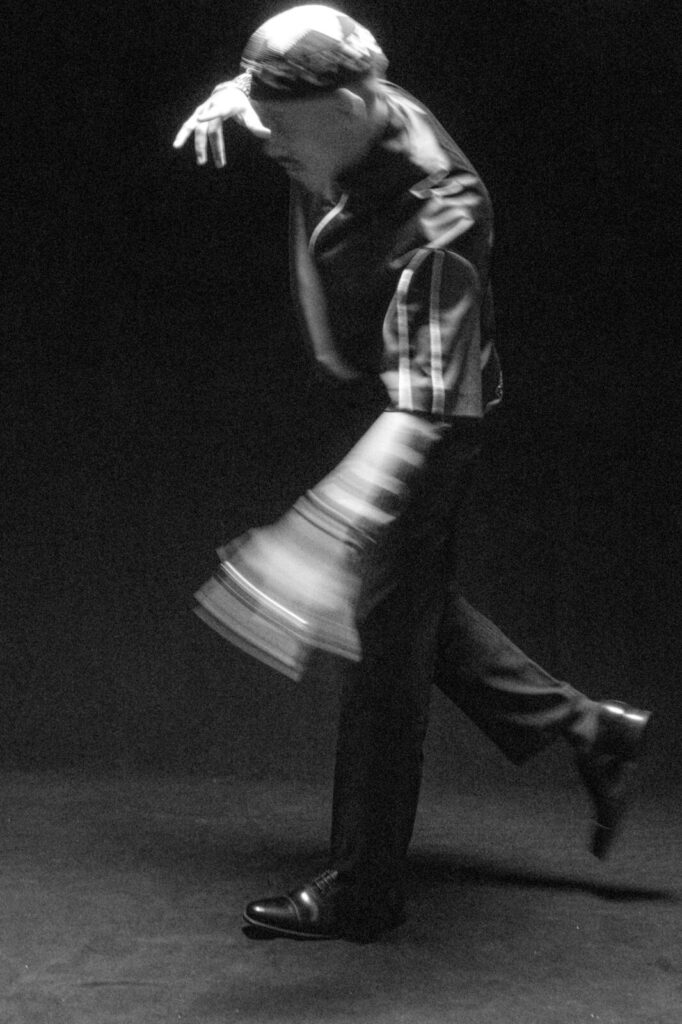

RHR: Gíria also echoes another Portuguese word: girar, “to spin”.

The entire concept of the EP revolves around movement – circular motion, spiraling energy, the idea of returning to the same point transformed. My music has always been influenced by capoeira and Brazilian percussive traditions, which carry this physical and rhythmic sense of rotation and continuous flow.

After releasing En-Giro, my previous EP, Gíria felt like a natural continuation.

It’s as if each project of mine moves in the same orbit. In music and in life, the search for meaning is a spiral. You revisit the same place, but you are different when you arrive again.

CM: Do you have a specific philosophy you turn to when making music?

RHR: The upcoming EP belongs to the universe of symbols and codes that I always weave into my work. I like creating elements that resonate with people who share something with me. But also with those who don’t. Whether it brings comfort, discomfort, curiosity or tension, I want my art to generate movement.

CM: And how does this connect to the sounds that influence you? In a previous interview you’ve said that you want everything you do to have a “Brazilian sound”, even if the tracks you’re playing aren’t Brazilian. What gives something a Brazilian sound?

RHR: When I say that, it’s about the rhythms, the attitude and the way of bringing different elements together to create a cohesion full of syncopations and polyrhythms, aggression, and softness, like in Brazilian music. It’s more about the feeling than the styles themselves. The places where I lived always gave me this synthesis of ideas and that’s how I approach music.

In my music, baile funk is a constant presence because it’s part of my roots, my memories, the places where I grew up and lived. I was also raised listening to forró, rap, and reggae because of my family, especially on my mother’s side.

But what truly defines my work today is the way I merge rhythms, textures, and sonic philosophies. I’m globally curious – I explore sounds from many territories, always with respect and awareness. Even as an artist from the Global South, even as a brown person, I understand that cultural appropriation happens in many ways. So I never position myself as “the artist” of a culture that isn’t mine. I position myself as someone who listens, learns, and translates through my own lens.

And on a technical level, I’m fascinated by intense sound design: aggressive mixes, powerful engineering, textures that carry a sense of territory within them. I love when a track reveals a place — when the music transports you through its rawness, its impact, and the history embedded in its timbre.

CM: Baile funk is a genre that has been adopted across the global funk landscape, but which is still facing attacks in Brazil. In June this year, a São Paulo municipal councillor proposed that any artists funded with public money must vow not to “promote organised crime” in what has been called the “anti-Oruam bill”. Why are the Brazilian powers-that-be so scared of baile funk?

RHR: The Brazilian middle and upper classes cannot tolerate the idea of people from the periferia [urban outskirts] circulating in the same spaces as them. Baile funk emancipates people financially and, beyond that, it is the music where young people tell their raw reality, whatever it may be. That reality is often not easy at all and is marginalised by these groups, which are largely represented by right-wing politicians. And so, for example, when a young Black person from the periferia like Oruam, who has many fans and is loved, talks about this reality, they try to criminalise and marginalise it out of prejudice, arrogance and a rearrangement of power.

CM: What’s your view on the right-wing position that baile funk glamorises crime?

RHR: The idea that funk glamorises crime is prejudiced. If a filmmaker makes a movie about the mafia, do they become a mafioso? No, they are portraying a story. The ex-president and now inmate, Bolsonaro, made an apology for crime in several of his speeches. That is glamorising crime. Funk talks about the reality of the periferia; these are stories being portrayed, some of which have truly been lived. An MC portrays what they live; there’s no such thing as glamorising. Anyone who is in the periferia and lives there daily knows what the reality is “crime não é o creme” [the phrase is that is difficult to translate, but which roughly comes out as “the crime ain’t the cream”].