It has been less than a year since David Lynch’s passing, and the outpouring of love and grief from his fans around the world continues to be felt. Among the many tributes honouring this iconic director and his truly unique, Lynchian worlds is MUBI’s newly released podcast series, Ladies of Lynch. Through conversations with some of Lynch’s closest and longest-standing collaborators, host Simran Hans explores the complex, subversive, and remarkable women who have been at the centre of his cinema, both on and off the screen.

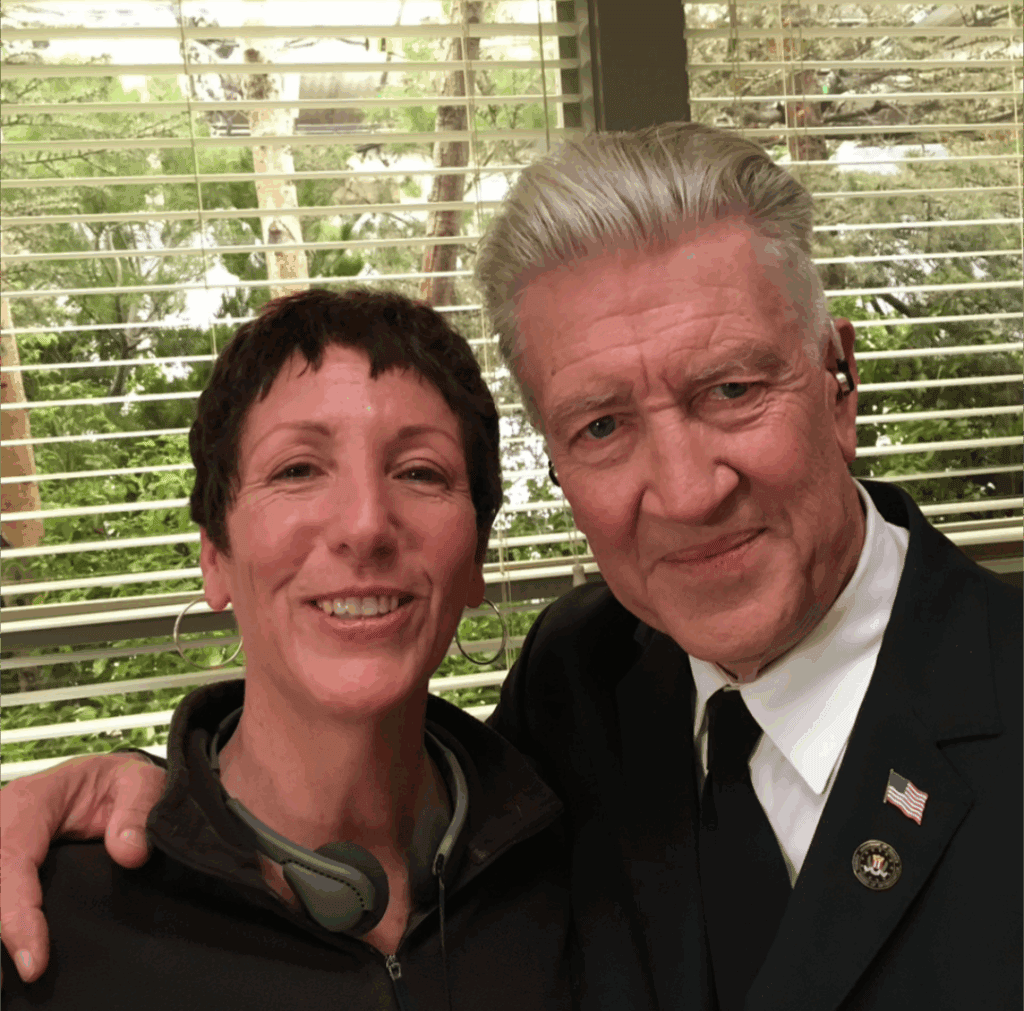

Among these collaborators is Sabrina Sutherland, a long-time producer on many of Lynch’s projects and long-time friend. The Cold Magazine had the incredible pleasure of speaking with Sutherland, who shared the story of how she first stepped into Lynch’s orbit after watching Twin Peaks and knowing she simply had to be a part of it, a decision that would lead her to join the team for its second season and begin a creative partnership that would span more than three decades.

From those early Twin Peaks days to later projects such as Inland Empire (2006) and even the delightful COVID-era Weather Reports on YouTube, Sutherland reflects on a lifetime of collaboration and friendship with one of cinema’s most visionary artists, and how she continues to champion his work and legacy today.

Cold Magazine (CM): I was listening to the podcast, and I heard you say that your connection to David Lynch really began after watching season one of Twin Peaks, which led you to reach out and becomeinvolved in season two. Can you walk me through that moment? What was it about the show that made you feel so strongly that you just had to be involved?

Sabrina Sutherland (SS): I was working on another TV series at the time called Sunset Beat, starring George Clooney. We were shooting nights, and back then I could record shows on VHS. So, around two in the morning, when I was supposed to be working, I’d pop in the VHS tape and watch Twin Peaks, because it was just that good. A few of the people working with me wanted to see it too, so we’d all gather and watch while we were technically on the clock. We were waiting around for work, so we had the time, but still, it felt a little sneaky. I can’t even describe it properly – the show was so different, so creative, so unlike anything else on television. It completely pulled me in. I couldn’t get enough of it. We watched it every week, religiously.

At some point I just thought, Okay, when my show’s done, I’m going to call and find out about working on this. I was sure it would be picked up for another season. So as soon as Sunset Beat wrapped, I called. I was lucky enough to go right down, talk to them, and get the job. I honestly couldn’t believe it. That’s the only time I’ve ever done something like that, just reached out on a whim, but I’m so glad I did. I’m not usually that kind of person, but Twin Peaks hit me so strongly. It was just incredible.

CM: Once you got on that set, you were suddenly in the middle of this incredible cultural phenomenon. What did it feel like to step into that whirlwind at such a pivotal moment?

SS: It was really interesting, because so many people wanted to do the same thing, send in résumés and try to work on Twin Peaks. I remember one girl even sent me a pie, and when I opened the box, her résumé was sitting right on top! People were doing anything they could just to be part of the show.

When it first started, I think even the actors weren’t entirely sure it was going to be the success it became. But being around them, you could just feel how kind and genuine everyone was. For the most part, everybody was there and just happy – like, excitedly happy – to be part of it. That’s exactly how I felt too. There was just this sense of excitement, something I can’t quite explain. It was wonderful. Really wonderful and amazing.

CM: From there, you became one of Lynch’s longtime collaborators; what I’ve always loved about him is how many women he surrounded himself with, both in front of and behind the camera. Could you describe what it was like to become part of that remarkable creative network?

SS: I was so, so lucky. A lot of it had to do with working through the years with David’s wife and collaborator, Mary Sweeney. I worked very closely with her, and I think from the beginning, David always just wanted the best person for the job. He was never sexist or misogynistic in any way. In fact, he really embraced women, he respected and valued what women had to offer. I’ve met a lot of men who aren’t like that, so it was exciting and refreshing to see how much he trusted women. As our relationship grew, I realised he was truly a champion, not just for women, but for hard work and integrity. Everyone wanted to work for David. You could feel it. People genuinely wanted to make him happy, it was almost like wanting to please your parents in a way.

But what made him so special was that he acknowledged and respected what I brought to the table. He trusted me to handle things responsibly, and that meant a lot. I’ve worked with people who didn’t show that same respect, so it stood out even more. David just loved people, he appreciated everyone equally. I feel incredibly fortunate to have met him and to have been able to work so closely with him. It truly has been the best thing in my life.

CM: Lynch never shied away from depicting the violence and trauma women experience in everyday life – something that still resonates deeply with audiences today, especially among young women. You’ve worked on projects that explore these themes, like Twin Peaks and Lost Highway. From a producer’s perspective, what was it like guiding those stories while working with such challenging and potentially triggering material?

SS: That’s a great question, because I do see people sometimes pigeonhole David, thinking he doesn’t like women or that he portrays them in a negative light. But I actually think it’s quite the opposite. David shows the darkness that exists in the world, but he also reveals the light that shines within it. He’s a very spiritual person, and his care for women is absolutely there. I think what he often does is hold up a mirror to the world: to the stereotypes, to what’s happening to women, and to how society views them.

Even when he was talking with the actors or shooting scenes, he was so gentle. There was never any anger toward women at all. It was about embracing women, upholding them, and showing that they’re really worthwhile people in this world. They’re human, and these terrible things that happen to them, that’s not the way the world should be. I think that’s really what he’s showing. I just can’t imagine how people misconstrue that and see him as being negative toward women. I don’t see that at all.

CM: Perhaps what makes David’s portrayal of women so haunting is that his women are so complex and human, but at the same time represent various cultural signifiers. I’ve always loved the recurring blonde/brunette interplay, with the blonde often representing the girl-next-door and the brunette a more sensual side of the same coin. From your perspective working on these projects, how often was that kind of dynamic an intentional part of the film or series, and how did it influence production choices?

SS: Well, David always told me, whether it was for casting or anything he did, he would have an idea. Something would just come to him, whether it was through meditation or while he was writing. An idea would form in his mind, and whoever he saw, that’s who he wanted for the role. He never really knew how those ideas came to him. Especially in meditation, he felt like things were just flipped to him; like they weren’t his own ideas, but were given to him.

So for the women in his work, or really any character, I think the “look” was simply the image that came into his head. A lot of times, even aside from women, when we’d talk about casting, someone might suggest, “Hey, here’s this lead role, it’s a man. What if we made it a woman instead?” And David would say, “No, no, the idea is, it’s a man.” It was the same with everything he did. He had a very specific vision of what he wanted to see. Maybe some of that came from his subconscious, I don’t know. I don’t know if he preferred brunettes to blondes or anything like that, but honestly, I think he just loved women. I don’t think he cared what they looked like – he just genuinely liked women, respected them, and loved them.

CM: Since you mentioned his love for Transcendental Meditation – which has become such an iconic part of his process – I read that he once suggested it to you and that you’ve practiced it ever since. Could you tell me a little about that experience?

SS: Oh, absolutely. I remember exactly. I was working on a commercial with him, and we had just finished. He was editing, and I came up behind him, and he turned to me and said, “You know, I think you could benefit from meditation.” I’m not sure why he said that. Maybe it was because I seemed really stressed during that commercial or something. But he said, “I think you could really benefit from it,” and I said, “Okay.” And I think within days, if not the very next day, I contacted someone and said I wanted to learn.

He was really excited about that. He said, “Wow, I just told you, and you went right ahead and did it!” He was really happy that I did. And honestly, it changed a lot for me. Meditation has helped me not be as stressed or anxious. I still have anxiety, especially when I’m working, because I always want everything done right. I’m very detail-oriented, maybe even a little anal about making sure things are done properly, and that’s where a lot of my stress comes from. So he’s the one who turned me on to meditation, and it’s really helped. I only do the basic meditation – I never went further with the advanced Transcendental Meditation courses. I just do twenty minutes in the morning and twenty minutes at night. It’s my “me time,” and it’s a really wonderful feeling.

CM: Did it ever help you understand or visualise David’s creative process? I can imagine that being his connection to the physical world could have made your role both fun and complex – did meditation ever play a part in facilitating that?

SS: I don’t know. I mean, that’s an interesting idea, isn’t it? One of the things we did do, up through his passing, was when we were working together in the evenings, at four o’clock we would stop. We’d been in the office for a while; for many years, we actually shared an office, just the two of us. So we’d be working, and then at four o’clock he’d say, “Okay, it’s time,” and we’d put everything down and meditate together. During that time, I don’t know that I necessarily got into his creative stream in any way, but those meditations felt elevated somehow. I definitely felt more of a release, and more creativity, than when I meditated by myself. So there’s something to that, I think – I just don’t quite know what.

CM: Beyond film and TV, you also managed Lynch’s YouTube presence, including the daily weather reports. Recently, a 2005 clip resurfaced where his “words for the day” are “to and fro,” as a woman sways next to him in what he described as “a somewhat surrealistic moment.” What was it like to shape and preserve these charming, deeply Lynchian fragments of his creative world?

SS: Oh, gosh. Well, for example, that clip came from DavidLynch.com, so that was before the YouTube channel. David loved those short films and all the little pieces that could go on there. The YouTube channel we did during COVID, and a lot of those earlier pieces were put on there, but the new ones we made – it was almost a distraction for us during that time, because our show was shut down. I was kind of pushing David, saying, “Hey, let’s do something while we’re sitting here. Let’s do something entertaining.” He said, “Let’s do the weather report again,” because he hadn’t done it since the DavidLynch.com days. I thought, great! So we started doing that every morning. Then I said, “Why don’t I shoot some video of you? It’s fun, people want to see that.” And he said, “Okay, well, maybe it’s ‘What I’m Doing Today,’” and we did those little videos.

He also made some short videos, and I wanted him to do even more, like animation and other short films, but he wasn’t having it. He wanted to paint. But for a while, it was a lot of fun – for me, definitely, and I think for him too. Until it started to distract him from his art, which was really where his focus was.

CM: I’ve seen some beautiful tributes and a renewed love for Lynch since his passing. I know the Prince Charles Cinema has organised Twin Peaks showings with black coffee and pie, and now that the series is on Mubi, there’s been so much rediscovery of his work. As audiences continue to find and revisit his films and shows, what do you hope they take away?

SS: I think, for the most part, David was a visionary. Everything he did was advanced, so ahead of its time. I just hope new audiences can see these works in the context of when they came out.

For example, Fire Walk With Me, Mulholland Drive, Lost Highway – when those films were first released, they weren’t well received. You know, being booed at Cannes is a terrible thing. They just weren’t appreciated then. But now, to see how they’re valued, I hope people understand how much of a visionary he was, how creative, how truly unique. Nobody is like him. His mind was something extraordinary, and his presence is such a huge loss for the world.

I also hope people look at his work and keep finding new things in it every time they watch. That’s what I do. I’ve seen Lost Highway many, many times, and each time I take away something new. I think he was creating for humanity, his art was about human beings. He was a very spiritual person, always thinking universally and broadly about the world and about people. He loved people. I hope that audiences take away that creativity, that vision, and that deep love for humanity.

Sabrina Sutherland’s conversation is part of MUBI’s Podcast Season 9: Ladies of Lynch, hosted by Simran Hans and available now on Spotify The season also features Isabella Rossellini, Jennifer Lynch, Mark Frost, and Deborah Levy discussing the women at the heart of David Lynch’s work.