I. Dogs and the Discipline of Power

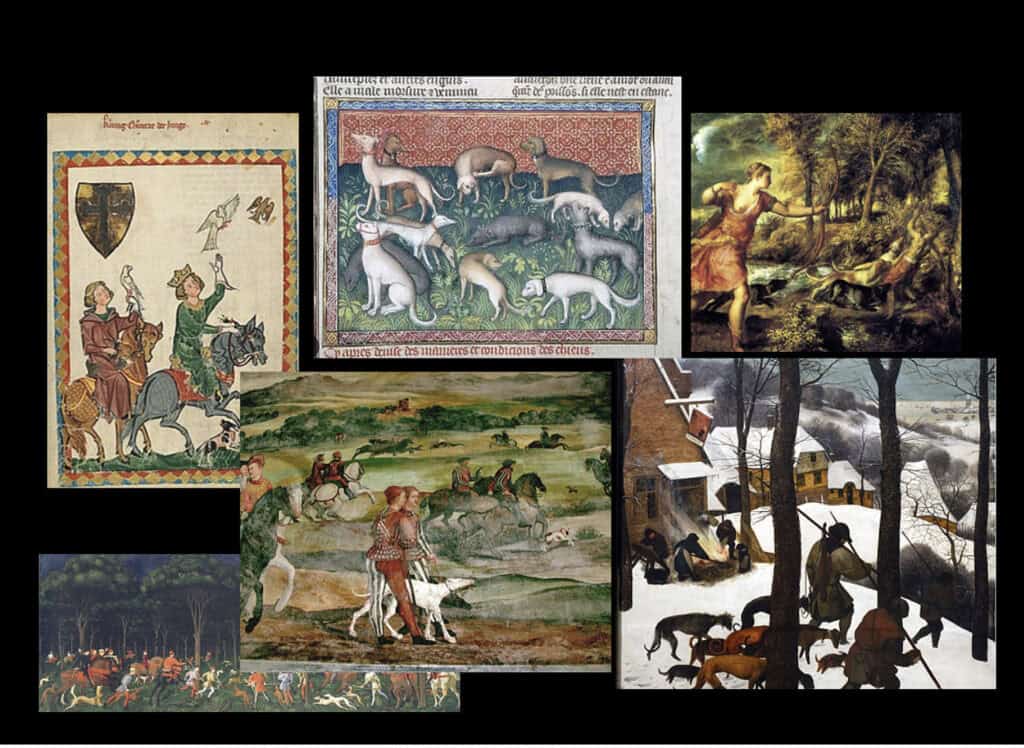

In older days, small, well-groomed companions were often painted alongside nobles and aristocrats, reinforcing their wealth, status, and mastery over nature. As French theorist Pierre Bourdieu might frame it, the dog served as a marker of embodied cultural capital – refined taste, control, and inherited power encoded through the obedient animal. These works trained the viewer to associate tamed animals with virtue, aesthetic extensions of the owner’s disciplined world.

The contemporary array of half-ill pedigree dogs and artificial designer breeds like Labubus may continue to signal belonging, but in a more liquid, affective economy. Instead of symbolising inheritance, they embody ephemerality: dopamine-driven identities, algorithmic charm, and fleeting emotional capital. The dog is no longer a reflection of stability but our own domesticated adaptation to contemporary attention culture.

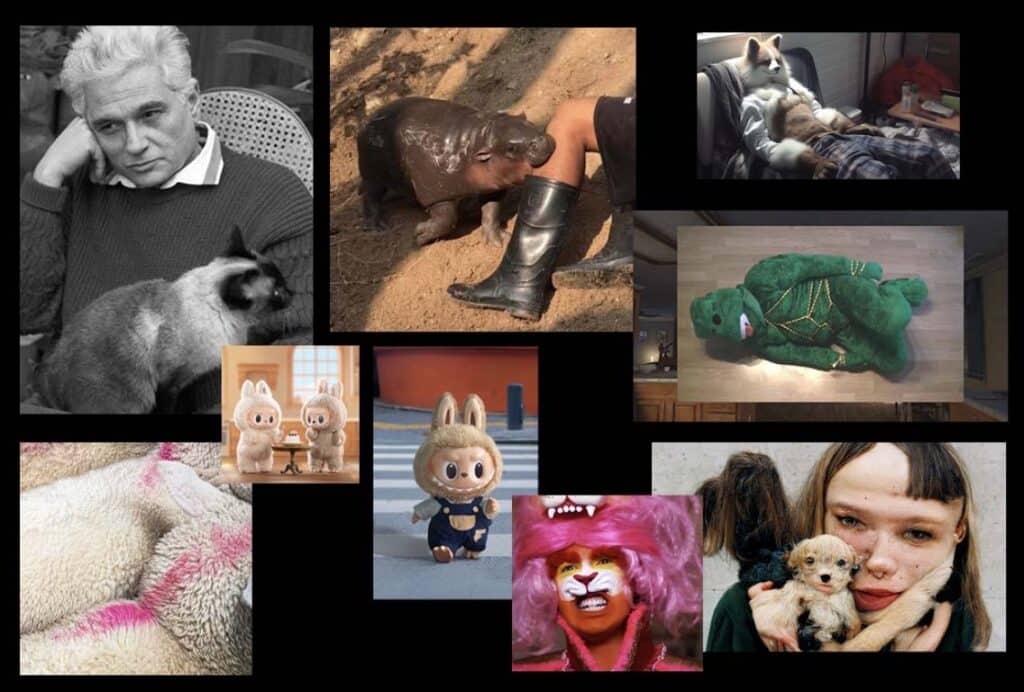

These are the themes explored by OHSH Project’s PEDIGREE show, which sets the stage for further thinking about how pets move between loyalty, grotesquerie, and disruption while carrying historical weight and digital volatility. From Jacques Lacan photographed with his cat to viral pygmy hippos, Kasing Lung’s Labubu figures, and endless TikToks, animal imagery circulates as both a symbol and commodity.

II. The Uncanny Canine

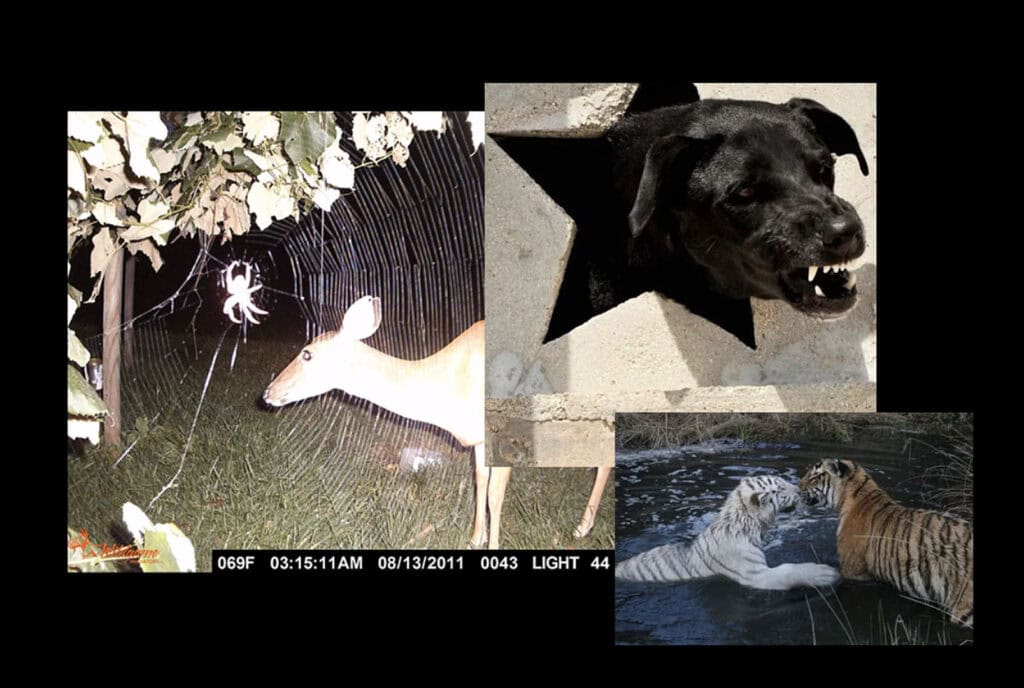

Today, the dog no longer sits easily in its role as loyal companion. Instead, it flickers between registers: cute and disconcerting, intimate and alien. Dogs have long stood as proxies for human nature: domesticated over millennia, shaped not only by evolution but by the desires, fears, and fantasies of the people who live beside them. A volatile figure, this tension runs through PEDIGREE, examining how the domesticated dog can reflect the instincts, structures, and contradictions of human behaviour. The works on view trace this entanglement, showing how affection folds into control, and loyalty into legacy.

It is here that Mariia Annenkova’s practice becomes pivotal. Her series Intra-Species Park (2022) pulls viral canine imagery into painting, VR, and printmaking. Grainy screenshots and degraded files, sourced from the internet, are reworked into lush surfaces where intimacy collides with spectacle. Steyerl’s “poor image” becomes flesh.

Through these fragments, Annenkova stages the dog as a restless presence. When we look into the eyes of a dog — tranquil or snarling — do we catch a glimpse of ourselves?

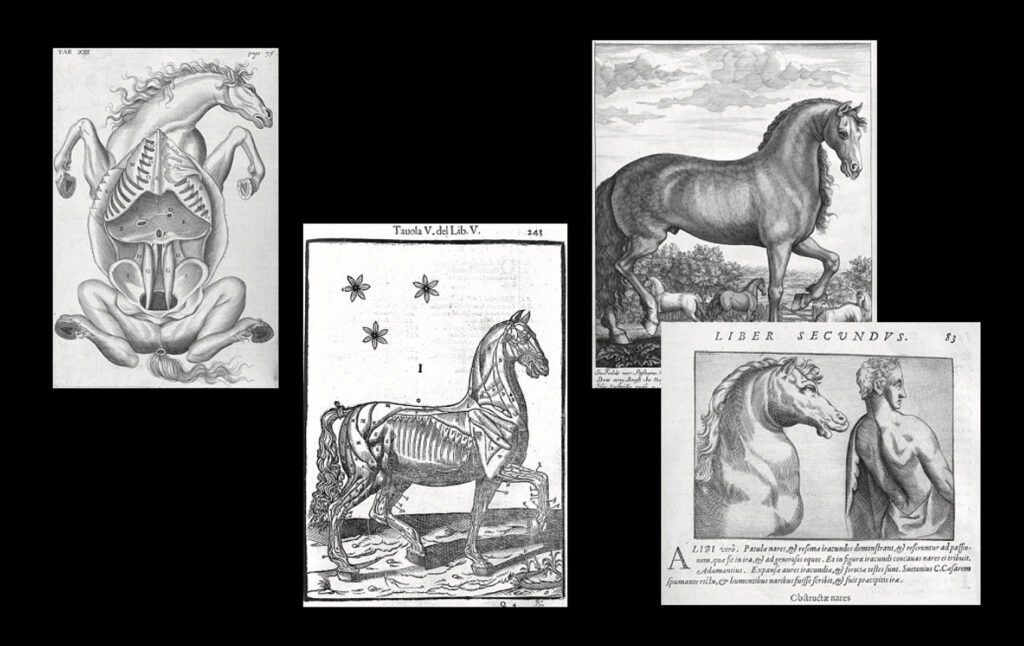

III. Unlearning Human Exceptionalism

To depict the dog only as a symbol of loyalty or obedience is to reduce it to a human metaphor. In Unlearning the Animal, Annenkova calls for a shift in how we approach animal representation: not as static icons, but as sites of agency and relation. Her work reframes the animal not as an object to be studied or aestheticised, but as a subject with whom we share space, vulnerability, and intensity.

It is precisely this idea that PEDIGREE takes up, positioning the dog not as allegory or ornament, but as a presence that unsettles human-centred ways of seeing.

By deconstructing these binaries, Annenkova’s practice unsettles the legacy of natural history. Her paintings operate as acts of unlearning, where the dog’s subjectivity is not flattened into narrative but rendered as presence — sometimes irritating, but autonomous.

In destabilising the established visual codes, painting becomes a method to practice humility, to acknowledge the nonhuman not as lesser, but as irreducibly other. In place of symbolic clarity, we’re offered proximity, friction, co-presence. The dog looks back — and does not ask to be understood.

In contrast to traditional depictions of dogs as noble, ornamental, or obedient, My Little Rascal (2025) uses charcoal’s raw immediacy to centre the animal in an unfiltered moment of abjection. The dog, caught mid-defecation, resists idealisation.The work confronts us with a form of intimacy that is bodily, messy, and unapologetically real. This tension – between affection and revulsion, devotion and transgression – is rendered through vigorous, expressive strokes that foreground the tactile materiality of the medium itself.

Charcoal, unlike oil or photography, does not allow for polish. It smudges, smears, and leaves traces, mirroring the dog’s irreducibility to a clean symbolic function. The dog in My Little Rascal is not a subject but a vector – one that pulls the viewer into a non-hierarchical relation. It is less a portrait of a dog than an invitation to dissolve the boundary between species, to occupy a space of collective, pre-verbal embodiment.

IV. Conclusion

Dog imagery is less an illustration than a laboratory: a way of testing ideas about domestication, sovereignty, care, and collapse. From Renaissance portraits of possession to posthuman notions of reciprocity, dogs track our ongoing attempt to unlearn human exceptionalism.

As Lévi-Strauss reminds us, animals are not just stand-ins for human traits but part of wider systems where meaning is constantly negotiated. What emerges is neither sentiment nor cold critique, but an ethics of entanglement: dogs as mirrors, companions, co-conspirators in our unstable becoming.

This is the ground on which PEDIGREE stands. Here, theory becomes an encounter: the dog looks back – not as a symbol, but as a co-presence — uneasy, insistent, already inside the experiment of what we are becoming.