With Sinners (2025), Ryan Coogler ventures into new creative territory, marking a shift in his filmmaking style. From Fruitvale Station (2013) to Creed (2015) to Black Panther (2018), Coogler’s films have always been upfront about the challenges, complexities and richness of the Black American experience. With Sinners, there is a shift in both form and focus. This haunting Black horror period piece – shot on 65 and 70mm film – drips with blood, longing, and Southern heat. It mixes classic vampire lore – holy water, garlic, wooden stakes – with themes of spiritual reckoning and racial trauma, breathing new life into a genre long dismissed as stale. It was a gamble to rework horror through this lens, but audiences embraced it: Sinners earned $122.53 million domestically, making Coogler the first Black director with four $100M+ hits.

Set in 1932 Mississippi, plagued by Jim-Crow Laws and poverty, the story follows the spiritual journey of Sammie (Miles Caton). He’s a gifted blues prodigy caught between religious duty and the pull towards musical self – expression. He lives under the watch of his preacher father who warns him at the beginning: if “you keep dancing with the devil, one day he’s gonna follow you home”. Sammie glimpses a way out when his cousins Smoke and Stack (both played by Micheal B. Jordan) return home from Chicago, with gangster cash and a plan to open a juke joint where Sammie can play his blues without shame. In the heart of Clarksdale, the club becomes a symbol of Black joy, freedom and resistance in a racially divided America. One standout scene, which watchers haven’t stopped talking about, comes around the 55-mark. Bluesman Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo) calls up Sammie, like a pastor summoning a deacon to deliver a sermon, to perform “I lied to You”, a song about sin, confession and desire. Shot in a 4:3 ratio – best experienced for IMAX – this particularly energetic musical scene (which alone makes the ticket worth buying) explodes with reverence for Black cultural heritage.

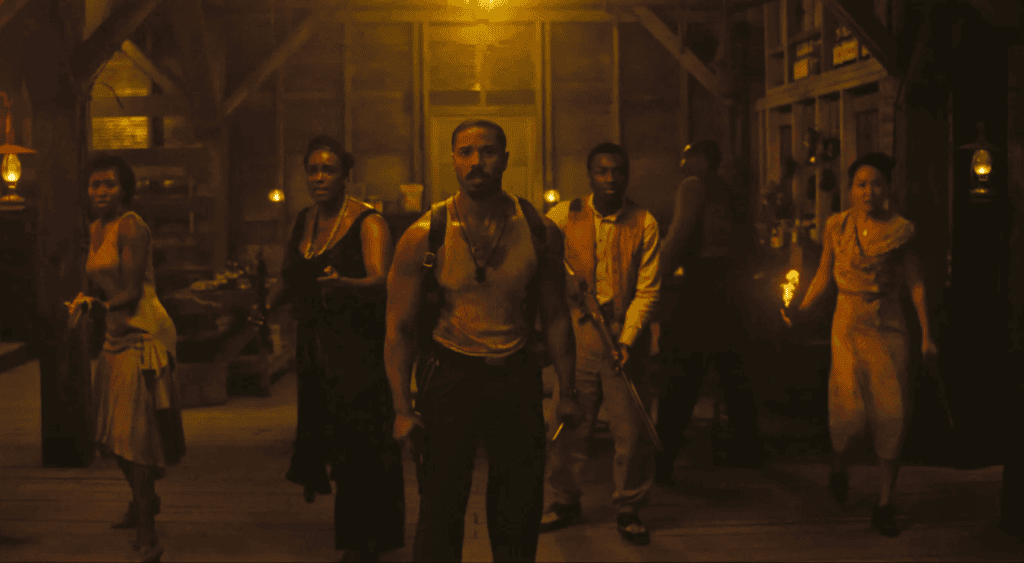

But punters soon find themselves quite literally dancing with the devil when the joint is ambushed by bloodthirsty (incidentally white) vampires, led by the sinister Irishman Remmick (Jack O’Connell) and a couple of Klansmen. What follows is a slow burning nightmare, creating a similar sense of paranoia evoked in Jordan Peele’s horror-satire Get out (2017). There is something off about the newcomers lingering at the club door. Their smiles are plentiful – but stretched just a little too far. Danger brews beneath the surface long before you can explain it. And as the party goers begin to fall one by one and the night spirals out of control, it soon becomes clear that Remmick and his vampire crew are after more than just blood. They have come, with their whiteness, to feed on Black creativity, culture and spirit.

In particular, African-American music – its power appropriation and exploitation – are heavily explored throughout this film. Composer and executive producer, Ludwig Göransson’s phenomenal Delta Blues soundtrack is homage to the pain and resilience of early 20th-century Black Americans post slavery. Originating from the cotton plantations of the Deep South, specifically in Mississippi Delta, it is a genre born from solitude and rural hardship. These qualities are inseparable from the physical landscape itself, which cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw captures beautifully through wide shot angles. Coogler narrates, with remarkable clarity, the duality that blues music carries. Inherently melancholic, shaped by the racial violence and suffering endured by its creators, it also carries a profound sense of empowerment. Born out of 1930s juke joints and street corners, it has become a sacred vessel through which Black subjectivities are both expressed and affirmed.

Whilst revolved around the Black American experience, Coogler creates a world that acknowledges the complicated racial and cultural dynamics of the 1903s American South. The inclusion of a Chinese business-owning family, led by Grace and Bo (Li Jun Li and Yao), references the history of Chinese immigrant communities in Mississippi at the time. These communities played a vital role in the region’s economy. During the period of racial segregation, they would serve Black customers who were excluded from white-owned establishments.

Similarly, the integration of Irish characters, traditional folk music like “Road to Rocky Dublin,” and step dancing reflects the complicated process by which Irish immigrants in 20th century America negotiated cultural adaptation – a process marked by poverty, religious discrimination and attempts at cultural erasure. Arriving to America in desperate poverty – fleeing British Colonial rule – migrants were forced to live outside the boundaries of American whiteness. Remmick’s moral decay, then, echoes a historical trajectory in which the pursuit of acceptance and power meant abandoning solidarities with other oppressed groups. Rather than a simple story of good and evil, the film engages how histories of colonisation, migration and racism often shape identity in confusing and contradictory ways.

This is perhaps of the most important themes in the film: moral ambiguity. The ancient vampire rule, which holds that vampires cannot enter a space unless invited, feels symbolic when looked at alongside the opening scene in Sammie’s father’s church, where the congregation reflects on a bible verse that promises God will never place a soul in a trial without offering a way out. Salvation, we’re told, is always within reach – damnation is rarely forced upon us. The film does not simply ask whether we can be saved, but whether we even want to be. And by calling the film Sinners, the story reframes sin not as a singular act of wrongdoing, but as a fundamental condition of being human. We are all fallible, tempted, and capable of both good and evil.

This sentiment is carried right up to the very end, when a bloodied and battered – yet still alive Sammie returns to his father’s church like a prodigal son, met with open arms. The chance to make things right is still there, but Sammie decides to go his own way and stay true to himself. Coogler then jumps ahead to 1992, where an older Sammie is seen performing at a club, played by no other than the legendary Buddy Guy himself. He’s achieved his dream of becoming a traveling musician, but the scars from that fateful night still mark his face. In a surprising mid-credits twist, Sammie is confronted by two remaining vampires who offer him the chance to live forever. But he refuses. In this moment, it becomes clear that Sammie has turned away from both religious salvation and the allure of enteral life, choosing instead a raw, imperfect but genuine freedom found only in the blues – the music that speaks to the very essence of who he is.

Between the phenomenal performances by Michael B. Jordan, Hailee Steinfeld, Delroy Lindo, and Miles Caton (to name just a few), the film’s impeccable pacing, and its evocative cinematography, Sinners stands out as a powerful watch in today’s social and political climate. The movie’s themes feel especially resonant in light of recent events -when just last month, the ‘Black Lives Matter’ mural near the White House, first painted in 2020, was removed following Republican threats to withhold funding from the capital. It’s a stark reminder that Black spaces – whether physical, cultural, or symbolic – are continually contested, built and dismantled under oppression. Sinners shows us that threats do not always arrive with obvious malice. Sometimes, the most insidious ones show up at our door with insincere smiles and a deceitful politeness. It is not only a piece about survival, it is about protecting and fighting for what is yours, and sharing it with those you love the most. It is funny, joyful and deeply moving – a reminder of just how magical cinema can be.