For close to fifteen years, CN Lester has run TRANSPOSE: a versatile and fluid evening of performance, now in its regular home at the Barbican’s experimental studio venue, The Pit. This particular edition of the festival sees curation from the co-founder and creative director of Trans Voices UK, ILĀ, whose shaping hand offers a feast for the ears as well as a provocation for ways of listening.

This TRANSPOSE is intimately concerned with questions of embodiment – what relationships we hold with our bodies, what it means to be bound (or unbound) by a body – continuing in the lineage of many trans theorists over the last few decades (one work engages obliquely with the legacy of Susan Stryker’s 1994 essay on Frankenstein). Blending various modes of live performance – opera, spoken word, dance, amongst others – the night offers up a new world in the form of the Subverse: a world which makes possible transformations, transgressions, and transportations.

I spoke with the creative team over email about live performance, dissociative listening, and the history of the festival, as well as what it means to be radical. It’s heartening to know that there is a space in one of London’s major cultural institutions committed to the platforming of new voices.

[The Cold Magazine]: CN, ILĀ, Jamie – thank you all for taking the time to speak with me. I wanted to start by asking all of you about your relationship to live performance. What does it mean to share a performance space with an audience and share your work live? What draws you back, time and again, to a space for collective experience?

Jamie: The reason I keep coming back to live performance is, at its core, the intimacy and unpredictability require such bonds of trust between audience and performer. Trust that the space will be held, the performer given room to perform, the audience taken on a journey that never exceeds what they can safely bear. Holding that space with an audience allows for an invitation into something that is powerful, vulnerable, and meets the incredibly primal need we have to experience and share stories. Nothing else allows for the same collectivity of experience. The audience shapes the performance, and the performance shapes the audience – it can never be the same twice.

CN: As a musician, I think I’d argue that music only exists in live performance and – as such – nothing else can exist without it. Music isn’t dots on a page – that’s only an aide-memoire – and even a recording created electronically rather than recorded live is experienced live, in sound, by its creator – and then co-created, in real time, by every subsequent listener. Being able to experience that process up close and personal with a creative, receptive audience is… well, everything.

ILĀ: For me, live performance is a state of entanglement. Sharing a space with an audience creates a kind of mutual permeability where we sort of get plaited together in real time. There’s a liminality to that exchange, a feeling that we’re meeting in a space that’s not entirely mine or theirs but something we co-create moment by moment.

In a world that’s increasingly online, that human connection feels rare and necessary. Live performance allows for nuance, vulnerability. It draws me back again and again because it offers a collective experience where people can feel something simultaneously yet differently. An embodied reminder that we are, for a brief time, in relation.

[CM]: CN, you’ve spoken of how live performance possesses the capacity to “illuminate […] what has previously been hidden” – I was wondering if you could speak on what the light of TRANSPOSE has uncovered in its almost 15-year history, and what you hope that this particular edition of TRANSPOSE will illuminate?

CN: Looking back right from the start to now, I’d say – that there’s really no such category of “trans art” – only a constantly developing set of works – individually and in conversation – from trans artists. And that there really is no limit to the imaginations, forms, and interdisciplinary discoveries of those artists. For SUBVERSE I was instantly hooked by ILĀ and Jamie’s ideas of the power building in an inverted world – the power that grows in the dark – and I hope audiences will be also.

[CM]: ILĀ, you are both curating and performing in this edition of TRANSPOSE, re-staging some of your work with Coda Nicolaeff as well as creating a new commission with Ray Felix Carter about reclaiming the concept of “dissociation.” McKenzie Wark, the incredible rave theorist, writes about dissociation as potentially “enabling” rather than “debilitating,” as a means to “find out things about the world” – what is the potential that you see in dissociation? Why are you drawn to dissociation as a mode, and what does dissociation make possible for you as an artist?

ILĀ: Dissociation first entered my work in a serious way after meeting McKenzie Wark at the trans*MEDIA conference at Harvard. Hearing her articulate dissociation not as a failure of presence, but as a potentially enabling state was exactly what sparked this line of exploration for me. It reframed something I had often experienced as a liability into a way of finding out things about the world that aren’t available through ordinary, “continuous” consciousness.

At the same time, at TRANS VOICES our approach insists that expression is valid without the narrow, normative idea of presence that so much vocal pedagogy assumes. Dissociation, too, doesn’t have to be “coherent,” “anchored,” or “behaving” to be meaningful.

So my attraction to dissociation is both personal and methodological. Dissociation creates a space where I can suspend the obligation to perform legibility of gender, of voice. In that suspension, other textures come through. These are not failures of attention, just alternate modes of it. As an artist, I’m interested in what becomes possible when those modes are welcomed rather than pathologised. It legitimises the unstable, the nonlinear, the dissonant, the disobedient. It lets me work from the edges of perception rather than the centre. And from those edges, I often find that the world becomes clearer, stranger, and far more possible.

[CM]: Jamie, you’re no stranger to The Pit at the Barbican, the venue for the past 10 years of TRANSPOSE. You’ve performed there as part of TRANSPOSE, you’ve curated Pit Parties for your own company, CRIPtic – what opportunities does the space present you with as director, particularly thinking about welcoming audiences into the Subverse that ILĀ has curated?

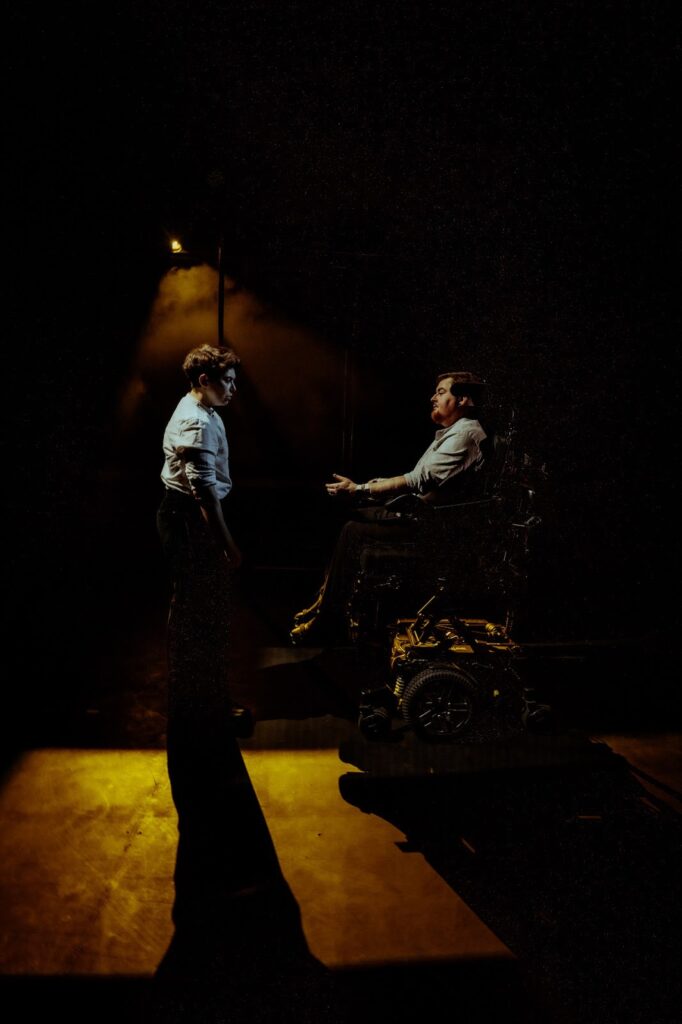

Jamie: The Pit is fantastic – it’s such a versatile space – a black box with marvellous technical possibilities and a fantastic team behind it. For Subverse, as the director I wanted to think about what it means to be working underground, literally deep in the Barbican’s subterranean belly, as well as metaphorically. To create something that felt like a lost or forgotten space, an abandoned world, an exclusive club, part dismantled. I thought about the Subverse as the part-made and the part-unmade, drawing on the ideas of uncertainty and superimposition of multiple states that ILĀ brought from their work as a quantum physicist. However, what really made that possible was the team at the Barbican, who designed the set and lighting in line with my vision but building it with their own expertise. I wanted somewhere that neither welcomed nor excluded the audience, that didn’t beg for its approval or charity, but where we could exist in our own exceptionality, on our own terms.

[CM]: CN, how has the festival grown and changed over the years? I’m particularly drawn to your incredible cohort of collaborators and how each curator necessarily delivers a personal iteration of TRANSPOSE – what have you discovered through their eyes?

CN: Thank you! The obvious answer – that when I started TRANSPOSE I was doing everything on my own – and that growing the event to the point where I could afford to bring in a series of new curators was not only freeing in terms of attention and workload, but in terms of both the show’s and my artistic development. Even if you try to resist it, there’s still a strong narrative of the lone artistic genius – particularly in music and literature, my two main fields. Actively going against that, and growing better and stronger through collaboration, has been a real gift, and crucial to the core of what TRANSPOSE is.

[CM]: Jamie, you’ve spoken about TRANSPOSE as an invitation to “commiserate, celebrate, and commit to changing the world.” How do you hold both suffering and joy together in performance? What is the function of each as we reach towards a better world?

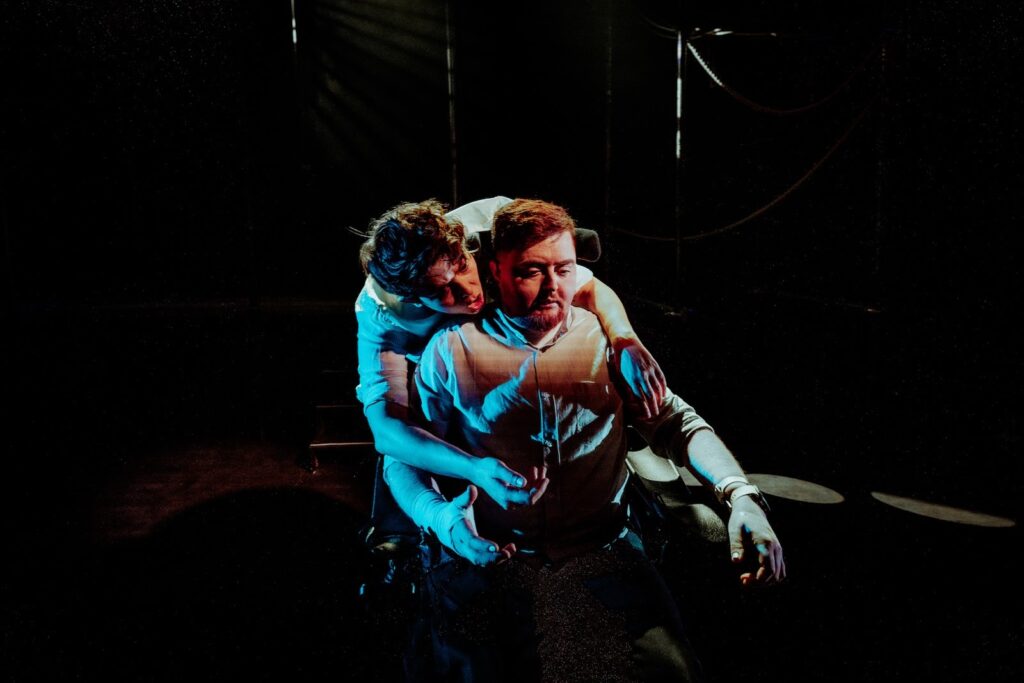

Jamie: Performance has so much scope for movement from suffering to joy. In Subverse I found both those in the care that we offer one another as performers offstage and within performances onstage. I tried to hold and build out those feelings in the way pieces were presented. I wanted to build tension between the beauty and joy in watching people reach for, and hold, one another tenderly, and the agony of that tenderness being necessary.

For me, TRANSPOSE: Subverse became a celebration of breath, rage, and survival, of searching and finding, and of being together. One of the roots of the word “celebrate” is “honour”, and I often think of it that way – that we aren’t just seeking joy but also honouring those experiences and moments in the way they deserve, whatever combination of joy and suffering they hold.

[CM]: ILĀ, I wanted to ask you more about dissociation – is dissociation something you feel to be in conflict with the nature of live performance as something inherently live, something present? Or does something unexpected happen when we direct our energies towards dissociation in a live, collective environment?

ILĀ: For me, dissociation isn’t at all in conflict with live performance. Because it’s not about trying to conjure dissociation onstage, but rather about allowing it when it appears and seeing what it makes possible. Instead of treating it as a break in presence, I think of it as another texture of presence. A shift in perception rather than an absence of it.

In a live, collective environment, that openness can create something unexpected. When I let dissociation move through the work rather than resisting it, the performance can enter a different register: slower, more porous, more intuitive. Audiences often feel that shift too, and it becomes a shared state of curiosity rather than a rupture. So dissociation isn’t a contradiction to liveness; it’s one of the many ways liveness can manifest, if we allow it.

[CM]: In closing, I wanted to ask all of you what it means to be radical, given that it’s an adjective so often applied to queer, trans, and many other non-normative performances, including TRANSPOSE. It’s a word that has come to mean so many different things, describing all manner of acts, as well as types of politics, beliefs, ways of being.

What does it mean, for you and your practices, to be radical? What pressures come with being radical, and how can art – and artists – answer these pressures?

Jamie: For me, radical change comes from the roots. Again, thinking of etymology, radical practices have to be radical throughout. You cannot present radical care in your performance if you haven’t practiced and applied radical care to yourself and your collaborators from the beginning. Work made radically is work that goes against what the industry would expect, both in what it contains and how it’s made. Radical work I think is not content to merely exist – artistically, it must provoke a change in understanding, or communicating, or being. We tried to make this work with care and compassion for each other and for the process, gently and generously, and for me, that was radical in a world that so rarely makes room for this.

CN: I’d echo Jamie – something cannot be radical without going to the roots – and that, for me, means doing the work to understand the multiple whys of our present moment, across time and across forms and communities, so that both the work and our working practices can actively build something better rather than be trapped in reactive shallowness. I think there is a general pressure for trans people to have to be experts – in our own healthcare, in arguments for our basic rights, in the endless discourses around sex/gender/sexuality – and I think the pressure on trans artists is similar. But…if I have to do that work anyway, then why not do it excellently and make it count?

ILĀ: To be honest, I don’t think I ever set out to be radical. I was called radical long before I ever claimed the word, simply because my existence, my body, my way of moving through the world already fell outside what most people recognised as normal.

And once that happens, you’re pushed (or maybe invited?) into a bit of an internal excavation. You start tracing the threads of your beliefs back to their roots, asking yourself: Are these ideas mine? Are they consistent? Do they hold? Where did they come from?

It becomes a process of unearthing, of pulling apart the foundations that were handed to you and rebuilding something that actually feels aligned.

The pressure of being perceived as radical is that people expect you to always be pushing, always disrupting, always performing a certain intensity of difference.

Art helps carry that pressure because it gives the weight somewhere to go. It allows us to sit with contradiction.