Wenhui Hao’s canvases extend far beyond the boundaries of abstraction. Her compositions carry a visceral energy that echoes the inner workings of the human body — its measures of life and the schisms that come with. Since graduating from the Royal College of Art in 2024, the Chinese artist’s paintings have become increasingly bound to questions of the female body and its transformations. Working with layered impasto and saturated colour, she probes: How do creation and destruction, pleasure and pain, prevail within the flesh?

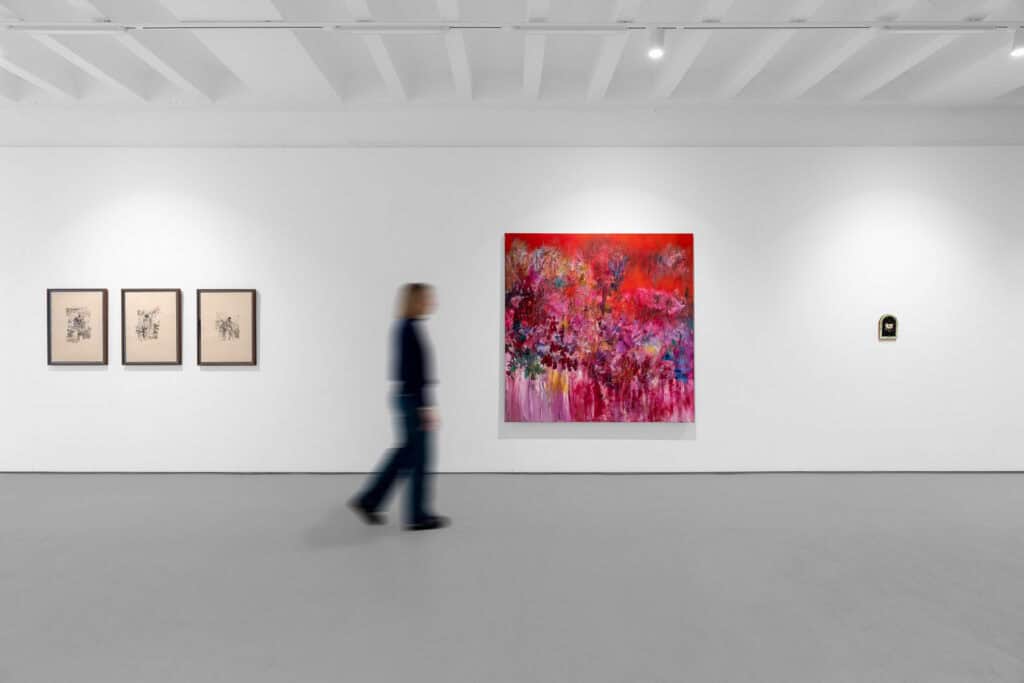

For Coming Up Roses at London’s Berntson Bhattacharjee gallery, Hao joins artists Preslav Kostov, Jemima Murphy, James Shaw and Xu Yang in a group exhibition exploring memory, emergence, and renewal. Here, her brushwork pulses with a rhythm and liquidity that reveals traces of wounds beneath layers of colour. In Uncanny Valley (2025), a large square canvas dominated by feverish reds, scattered blues, greens, and yellows, she evokes a body in metamorphosis, wounded and luminous. In Improvisational Dance (2025), Hao draws in cooler tones – this time punctuated by bursts of warmth spilling out from the bottom right. Across both paintings, lush surfaces conceal violence, and tenderness becomes visible only in the ruptures of colour that break through her brushstrokes – in the brief moments where the canvas melts away.

Before the opening of Coming Up Roses last week, I spoke with Hao about everything from the technical to the intimate. In our conversation, we discuss the intricacies of her practice, how her painting builds itself through instinct, and how certain memories remain quietly embedded beneath the surface. What is revealed through our interview is Hao’s gentle strength, a softness that mirrors the resilience of her body and the honesty of her own story, reflected in her artwork.

The COLD Magazine: When beginning a piece, do you work from a place of urgency or calm? How do your emotional states shape your process?

Wenhui Hao (WH): This touches on the very source of creation. When I create, the initial steps are a crucial moment in the painting process, as they establish the composition, atmosphere and emotional tone of the entire piece. My mindset at the time is rarely one of pure eagerness or tranquillity. It more closely resembles a storm in the making — that is, a premonition of the intense focus required for the coming hours. At the start, a clear, sharp feeling — anger, longing or ecstasy — informs my colour choices and whether I use a broad paint knife or a fine brush.

CM: Is there a ritual that shapes your practice?

WH: My rituals include brewing a strong cup of tea to help me concentrate, then playing my favourite music. I spend a long time touching the textures of unfinished paintings in front of me, reconnecting with their tangible memory through my fingertips before considering how to proceed. When facing a blank canvas, I make the first mark without hesitation — it might be a forceful way of wielding the brush, or just a splash of pigment. This act is not about creating a specific form, but about shattering that suffocating, perfect void. It breaks the silence.

CM: At first glance, your paintings can appear abstract, yet on closer inspection they reveal traces of the body, wounds and violence. How do you navigate that shifting boundary between abstraction and figuration?

WH: These shifting boundaries are not premeditated. They are born from the interplay between my painterly actions and intuition. In my work, I conceal naked figures within a flowing, fragmented wilderness where they flee, become hysterical or copulate. Sometimes, the landscape emerges first, while at other times, it’s a dismembered torso. But strictly speaking, concerning the boundary between abstraction and figuration in my work, I am not depicting — I am excavating.

CM: There’s also a strong sense of movement. How does gesture guide your process?

WH: The splattering of paint is an autonomous, material event. When I gaze upon these marks, fragments of bodies from my memory begin to emerge. An arc might suggest the curve of a spine. A thick, bruised accumulation of colour might evoke flesh and a wound. I do not paint the body; I recognise it from within the accumulated layers of pigment.

Then, I construct new layers through the continuous deconstruction and disruption of figurative forms using an abstract language. I will use more precise brushstrokes to shape a torso, or using transparent glazes to soften the edges of a bruise. What ultimately crystallizes on the canvas is a visible, rhythmic struggle between myself and memory — and with my own body.

Figurative language is a kind of symbol and narrative, while the unfilled, corporeal forms are a form of blank space — and also an uncanny valley. Abstraction, then, is both a compression and distillation of narrativity, and a material presentation of my instantaneous emotional experience.

CM: Your work draws on medical pathology, bodily trauma, and the act of suturing. What draws you to these topics?

WH: My interest in medical terminology stems from undergoing an abortion after an unexpected pregnancy. I found myself thinking about China’s One-Child Policy — a silent and oppressive period in history where many women were forced into abortions under threat of losing their jobs. Most women of my mother’s generation were compelled to have abortions due to this policy.

The entire summer I had my abortion, I bled continuously, while cold metal speculums were repeatedly inserted into my body. The air was filled with decay, humidity, stifling heat and pain. My memory of that time is tinged with a dark red hue. I also read numerous medical atlases on anatomy, childbirth and abortion procedures — and I see the process of repeated destruction and repair in my paintings as remarkably similar to this surgical treatment.

By the end of the summer, I felt as if my eyes could perceive more shades of red than before. I believe my paintings attempt to construct the complex life experiences of women. I want my work to possess a feminine strength. Therefore, I prefer my pieces to carry weight and density rather than lightness. I want my brushstrokes to be sharp, violent, and resolute.

CM: Coming Up Roses probes at the idea of memory and emotion. How do your pieces address those themes?

WH: They feature textures built from very thick paint and make extensive use of the painting knife to create frenetic and sharp strokes. In ‘Uncanny Valley’ (2025), I painted crouching, naked torsos concealed within red waterfalls and glaciers. In ‘Improvisational Dance’ (2025), I depicted a jungle teetering in a hurricane. They do not directly depict memory, but attempt to abstract, materialise and embody memory and emotion in the body.

CM: How do you approach a group exhibition compared to solo shows? Does the presence of other artists’ works shift your thinking about scale, subject or presentation?

WH: Participating in a group exhibition is like joining a dialogue. I contemplate, What voice will my work contribute under this shared theme? The visual intensity and expressive form of works in a group show require a subtle sense of coordination. So I consider, What size and tonal palette should my piece be? What role will its essence play within the overall exhibition? Other artists in group exhibitions inspire me and I find myself surprised. I’ll say, “My goodness, this theme can be approached from such an angle!” Witnessing the chemical reactions between the artworks of different artists in every group exhibition is also an incredibly thrilling experience.

In contrast, preparing a solo exhibition is a monologue. A solo show allows me to push an idea to its extreme and let the most intimate whispers resonate through the gallery space. The works must speak to one another to form a complete narrative.

CM: Colour operates as a key site of tension in your work: luminous and uplifting on the surface, carrying undertones of trauma and unease. What role does your palette play?

WH: Color is an essential language. Through the arrangement of light and colour within the composition, I construct complex, multi-layered spaces. High-saturation colours lend a fragmented quality to my expression. My surfaces are often thick, as each painting is built through prolonged reworking, layering, and reshaping. I am deeply fascinated by the material accumulation of multiple paint layers, voraciously capturing the unpredictability inherent in the painting process. I am absorbed in finding a precise balance between control and loss of control.

Color is also a metaphor for repair. Every hue on the canvas has undergone mixing, layering, and negotiation. Older colours are partially concealed by new layers, but they subtly permeate from beneath, shaping the final experience. It’s like how traumatic memories are not erased but integrated into the narrative of one’s life.

CM: The exhibition draws on Rococo and Baroque aesthetics — periods defined by sensuality, drama and excess. Do these historical styles influence your use of gesture?

WH: Unequivocally, yes. The sinuous curves of Rococo and the vortical force of the Baroque have not only influenced my brushwork, but they have reshaped how my body interacts with the canvas. My creative process is a sensory, theatrical drama performed upon the canvas.

In my practice, the theatricality of the Baroque transforms into an aggressive passion. Paint is hurled, slammed and dragged across the canvas, creating a violent sense of movement. This isn’t about depicting drama; it’s about letting the brushstroke become the drama. The paint nearly always splatters onto my face and hair. The sensuality of Rococo, meanwhile, manifests in the lingering, seductive quality of the stroke. I use the tips of small brushes, soft fan brushes, or the wool flat brushes from China for ink painting to trace soft curves reminiscent of silk folds.

CM: Are there any influences in your work that might surprise people?

WH: Some of my unexpected inspiration comes from food and anatomy. My exploration of abstract painting began with fruit. When I first started, I was constantly observing and depicting food, coming to recognise the profound connection between appetite and desire. The process of dismantling and cooking food is inherently violent.’ It is an indulgent manipulation that serves as an outlet for suppressed desires. I then found myself drawn to hollowed-out fruits brimming with seeds. As I emptied them, scooping the seeds from their cavities, I was suddenly overwhelmed with sadness. It felt as if I were violating the fruit, performing a kind of abortion on it.

During my MA, I painted a whole chicken that had been dissected, emptied, stuffed with sauce, and prepared for marination. In the Chinese context, the word for chicken is a homophone for prostitute — a metaphor laden with derogatory connotations towards women. The chicken’s back was studded with holes I had pierced with a knife and fork. Its form, with a hollowed-out abdomen and splayed legs, resembled ancient statues depicting childbirth.

CM: Coming Up Roses speaks of emergence and renewal. Do you feel this exhibition marks a turning point in your practice? Where do you see it leading next?

WH: The works in this exhibition are my final creations of the year. I am delighted to see that in my latest pieces, I have confronted my naked self more frankly, been more sincere with genuine emotions, and grown bolder and more confident in expression. I have thereby achieved a greater precision in using painting to convey feelings. My dream is to become a distinguished feminist artist recognised within art history. I believe that exceptionally curated exhibitions with such art-historical depth will guide me toward realizing this dream. Make a wish!

CM: And finally, when you step away from painting, what do you find yourself drawn to?

WH: I enjoy reading and watching musical performances, yet I find my greatest fulfillment in creative mediums that rely on imagery and materiality. In my daily life, I often work with film and Polaroid photography, and I also frequently enjoy watching films and experimental videos.

I am equally fascinated by the raw, untamed scenes of nature. I find myself compelled by eternally moving, ever-changing bodies of water — rivers, waterfalls, the sea, glaciers. I am obsessed with jungles, reefs, and valleys, often feeling their forms strongly resemble the stacking and folding of human flesh. When I take a break from painting, I use photography to capture landscapes. I am mesmerized by raw vitality, fragility, beauty, and terror.