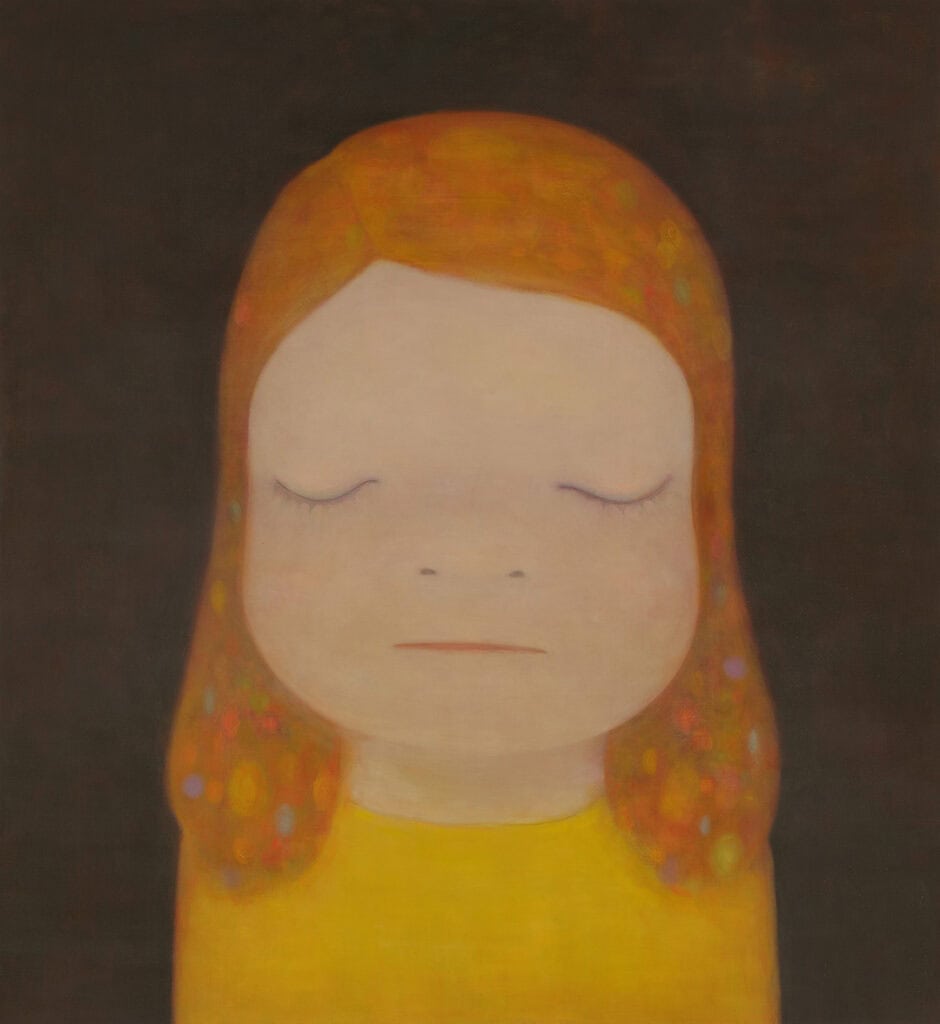

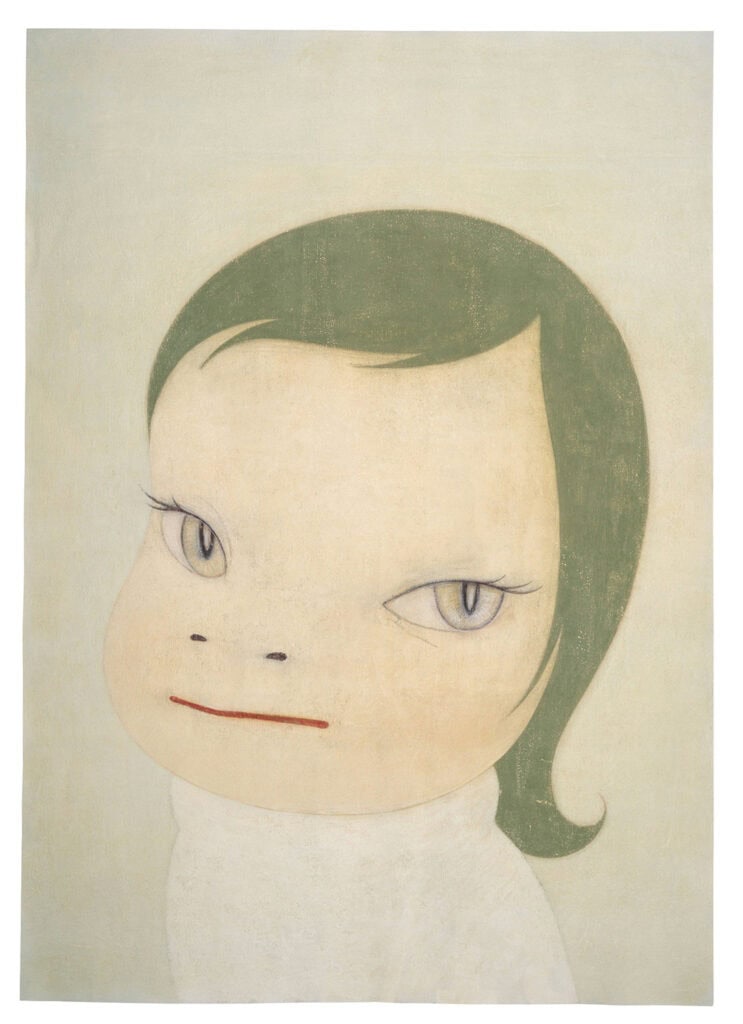

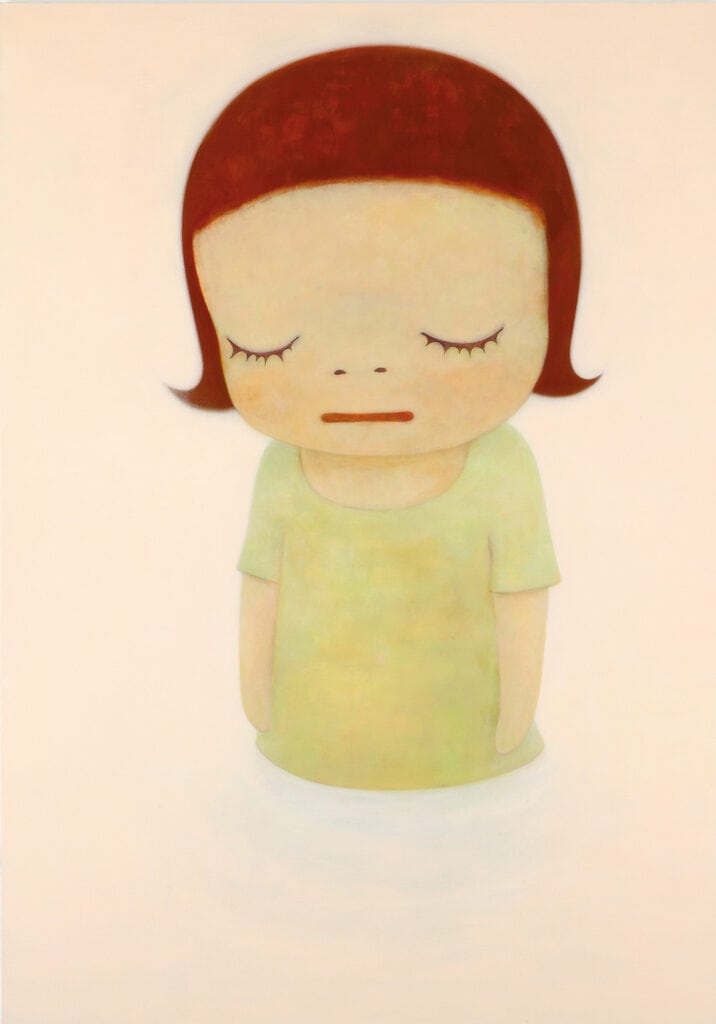

You’ll probably recognise the iconography of Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara, even if you don’t immediately recognise his name. Fat-cheeked and wide-eyed girls who stare unsentient (or sometimes hyper-sentient) into oblivion like Sonny Angels painted by Klimt. Punkish toddlers with vampire teeth and halting glares, demanding “NO NUKES” or thrashing-out to The Ramones. These figures, like strange anti-saints in the stained-glass church of postmodernity, have been abundantly decorating social media feeds, populating pre-Labubu blind boxes, and appearing on Stella McCartney runways for well over a decade now; they are also among the most expensive Japanese artworks ever auctioned off, and some of the most acclaimed to come out of the country in recent memory.

Now, they animate too the Southbank Centre’s Hayward Gallery in the first-ever UK public gallery exhibition of the Japanese counterculturist’s work. And it is absolutely the exhibition of the summer.

Archiving over 150 paintings, drawings, ceramics, statues, and installations which span four decades of production, “Yoshitomo Nara” marks the final stop on a European tour (the Guggenheim Bilbao; Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden) of what Nara quirkily describes as his “self-portraits.” Bunched thematically yet with chronological flourishes (the curator, Yung Ma, makes much of Nara’s relocation to Germany in the 80s, and the psychological effects of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake), the space becomes an Animal Crossing-like village of bobbleheads and therianthropic hybrids that tow the line between cherub and demon as much as they do that between human and animal.

The exhibition is, expectedly, an orgasm of otaku sensibilities, reflecting Nara’s genuine engagements with manga, kawaii culture, and the girlish pop-punk of outfits like Shonen Knife (with whom Nara shares a joyous love of The Ramones). Any visitor can consequently expect to find in the space decked-out digital nomads, sartorial inheritors either of Harajuku or Dimes Square (or both), posing before Nara’s gigantesque portraits for their Instagram cults. As a digital phenomenon, the exhibition seems destined to take over his countrywoman Yayoi Kusama’s torch, whose Infinity Mirror Rooms at the Tate Modern have monopolised artsy social algorithms for the last couple of years.

However, “Yoshimoto Nara” seeks to go beyond virality. Instead, it wants to situate Nara inside more conventional art history, spotlighting his Edo influences or inheritances from German Expressionism. It is here that the exhibition most dazzles, exploding the patina of social-media plasticity that may haunt his works to demonstrate the graceful technique and referentiality of his artform: shimmering textures that look lifted from a Millais, dreamy compositions that gracefully mirror Chagall.

Earlier, the exhibition opens with a monumental wall of album covers: Nick Cave, Aretha Franklin; inevitably, The Ramones. Nara has previously stated that, growing up in isolated northern Japan, the first forms of visual art he was able to engage with were album covers. John Hiatt’s Overcoats, for example, whose watery vivisection of forms his paintings abundantly reference. Meanwhile, Western music pilfered from a nearby US army base radio station became one of his earliest ways to connect with a world beyond himself. A world whose language he didn’t understand, but which spoke to him in a more embodied, more spiritual way. Even to this day, he says, he must deafen himself with sound in order to create, as if mirroring philosopher Simon Critchley’s claim that the fastest route to aesthetic ecstasy is simply through music (Critchley also cites Cave as a particular accelerant on this pathway).

This is all much more than a cliched union of “high” and “low” culture though, or even of “East” and “West.” There is a genuine worldbuilding to Nara’s work, a liminal, soupy, and childlike universe which the artist would undoubtedly identify as his inner world, the world of the soul. For, he explains in the exhibition’s press junket, these works are all “mirrors”; indeed, “self-portraits.” Meet the many eyes – some tear-licked, some mutedly monstrous – of his avatars and you may too enter these windows into Nara’s idiosyncratic soul-space. This is more than cutesy exhibit; it is a holistic invitation into another, internal place.