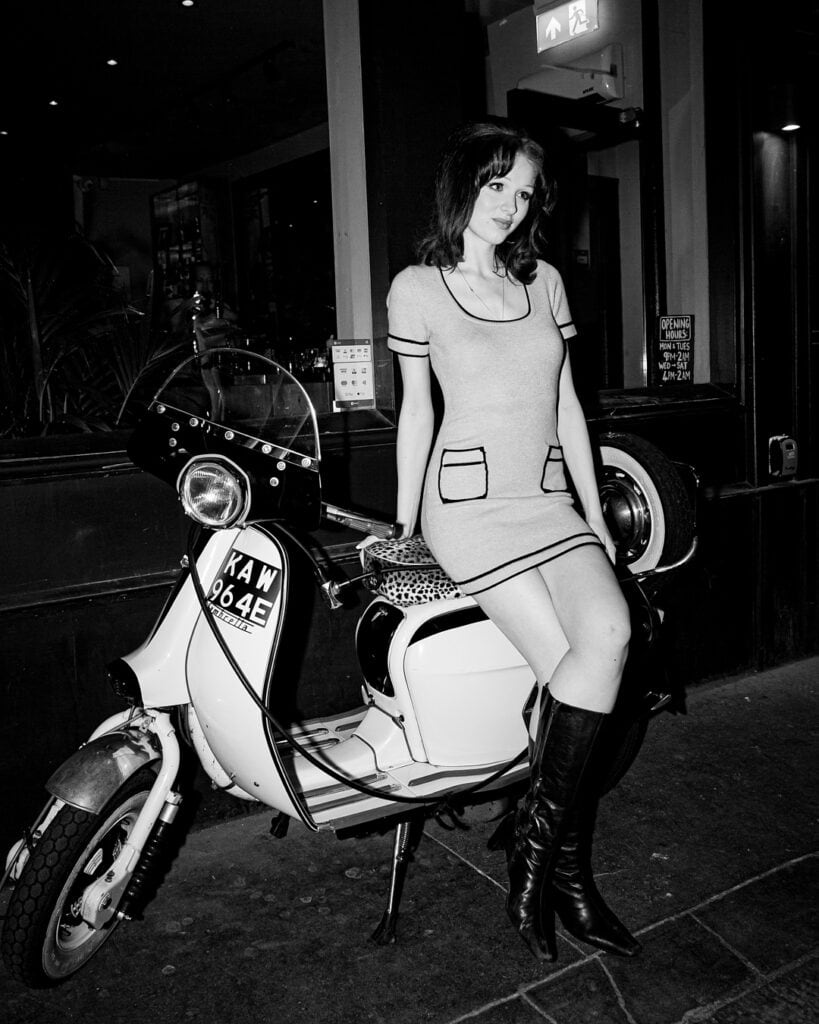

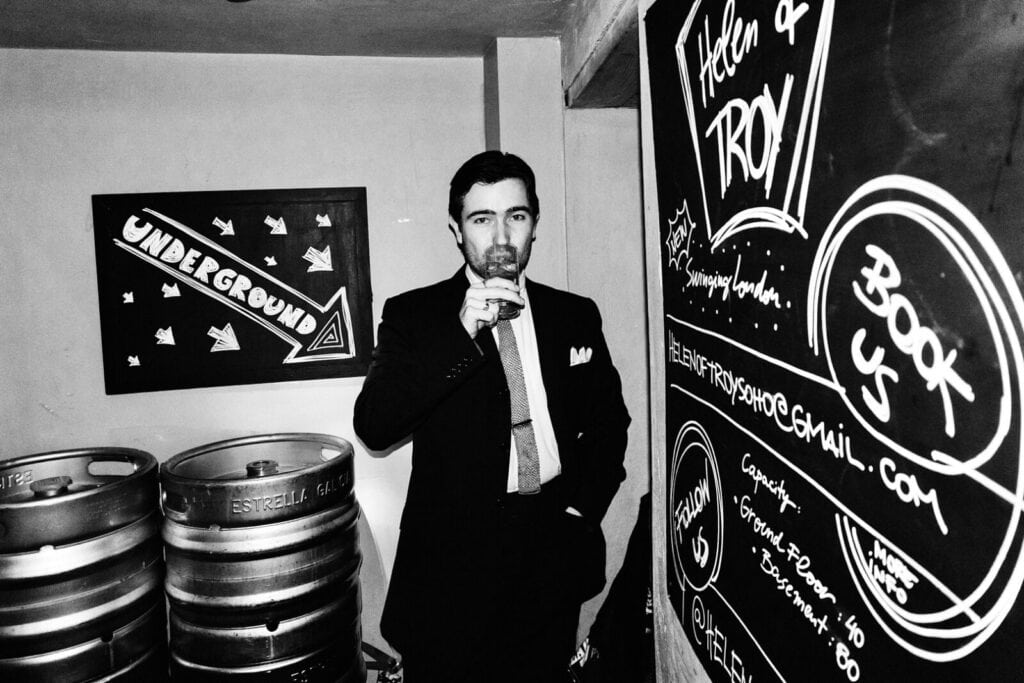

Turn down a shady alleyway in Soho and you might chance upon a sharply dressed crowd smoking Vogues by their Lambretta scooters. Hidden from the blinding lights of Tottenham Court Road, late-night dive bar Helen of Troy has become the newest haunt for an unlikely group of dapper youths choosing cufflinks over puffer jackets.

This year, Soho – the very neighbourhood where the Swinging Sixties started – has witnessed a Mod renaissance. The original post-war Mods reinvented what it meant to be young, modern and British. Fuelled by the rise of amphetamines, they danced to soul, jazz, Motown and R&B all night long to the ire of “respectable” England. It was described as “clean living under difficult circumstances” as working-class youths pulled together their wages to afford smart loafers.

Now, the Mods are back. But did they ever leave? Such scenes have long existed, but the age bracket didn’t quite qualify as a youth culture. “The established Mod nights cater to the older generation. They’re great but they have their audience,” says 27-year-old Tickety Boo co-founder Conor Bakhuizen. “We knew lots of younger people interested in the scene who had nowhere to go.”

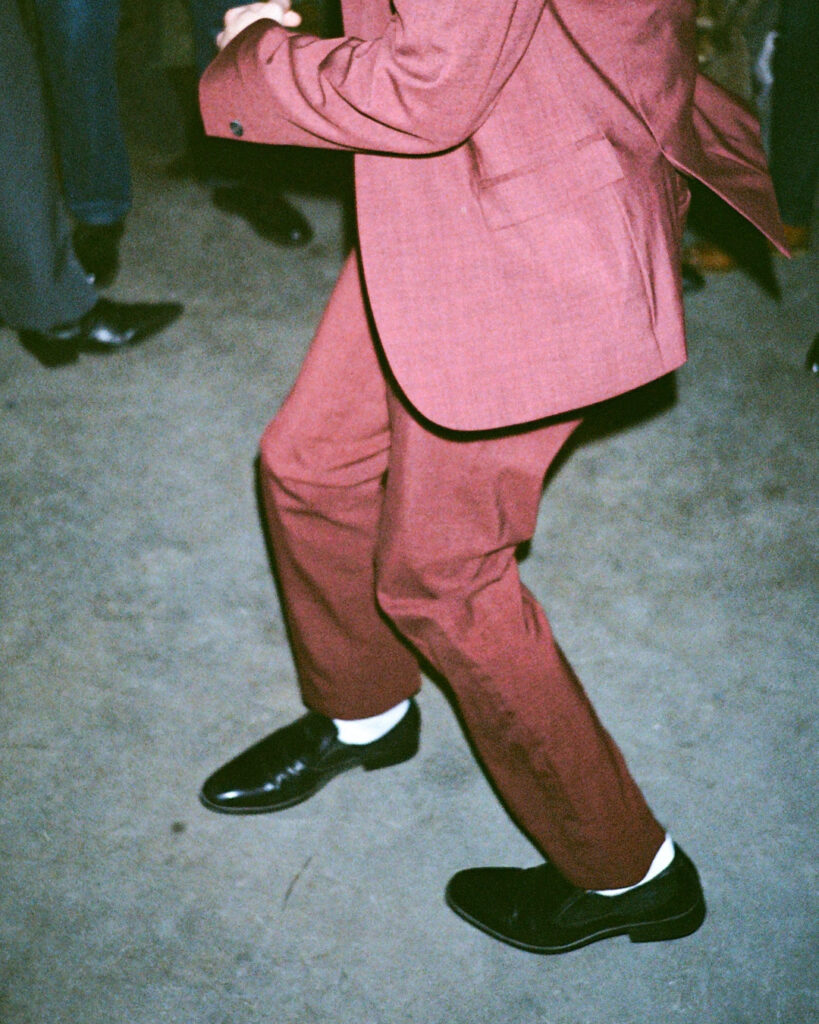

Tickety Boo, a vinyl club night, launched in April. The girls don colourful shift dresses, Mary Janes and Twiggy eye makeup; the boys buy tailored suits at the 1960s-themed store Sherry’s, where the Gallaghers have shopped for decades. It’s shaping an active London scene of bands and DJs who are inspired by the past but keen to shape their own identity – a palimpsest of the original subculture. “It feels great to be bang in the middle of it,” Conor says.

The dress code is strict. I didn’t achieve a blunt bob in time, but vintage clothes shopping I managed. Channelling Mod designer and inventor of the mini-skirt Mary Quant (a breakthrough that precisely coincided with the Pill, my photographer points out), I pick up a baker boy cap.

Inside the club, an old-school telephone is pressed to the DJ’s ear. I’m informed that it’s emblematic of the DIY working class origins – back in the day, the kids messing around with vinyl couldn’t spare the cash for fancy equipment, so they used a landline as makeshift headphones. What strikes me is that the attendees were raised like this. Their parents and grandparents are Mods. It’s a lifestyle, stitched into their taste, values and family history, not just a monthly club night. One glamorous girl in a long vintage gown and white fur, slightly bending the rules to go 1940s, says she dresses like that on a daily basis.

“It’s not great to be young in 2025, so there’s a lot of nostalgia around,” Conor says. “Being an online generation, it’s easier than ever to look back at a time when it was hopeful to be young.”

Gen Z’s desire for retro everything is undoubtedly linked to this youth culture revival. In a world of identical, unbreathable fast fashion and social life ruined by phones, the nostalgia is vicarious – they yearn for a lost past that was never even theirs. Young people crave unplugging from hyper-digital life, to belong to a scene and craft an authentic style in unique second-hand garments.

The massive Northern Soul revival witnessed over the last few years tells a similar story. Northern Soul was a dance movement that flourished in the North of England and the Midlands in the 1970s. As Ian Dewhirst, one of the original movement’s most iconic DJs, put it in a 2014 BBC documentary: “Even if you had a crap job Monday to Friday, Northern Soul let you go on autopilot and live for the weekends.”

New collectives have been born from the rationale that these scene – Mod and Northern Soul – were still dominated by an older vanguard. Now, Deptford Northern Soul Club and the Bristol equivalent have been credited with bringing free expression, energetic moves and fresh blood back to the dancefloor.

“The difference between the two movements is that the Mods wear suits,” one Tickety Boo regular tells me. I’m reminded of something my friend and rock journalist Rick Sky, who was a Mod in the 1960s, once told me: “We were sharp dressers – if you went to bed with a girl, first you would make sure your suit was hanging up with the trousers properly creased.”

Over the night, the film Quadrophenia (1979) comes up repeatedly – a cult classic that documents the violent clashes between the Mods and Rockers, notably the 1964 Battle of Brighton. The war between the rival subcultures saw over a thousand teenagers fight with deckchairs and pebbles on the beach, killing one and sparking mass arrests.

Historically, Rockers were the enemy, riding motorcycles in a leather jacket with a tough machismo. This rivalry has since toned down – but I’ve still seen big street fights between the punk, skinhead and goth subcultures in Buenos Aires.

After the Brighton punch-up, media hysteria ensued. British youth were depicted as trouble-makers indicative of societal decline. The events led sociologist Stanley Cohen to coin “moral panic” and “folk devil”. These describe the fear of a perceived threat, such as a new youth culture, often amplified by the media and politicians and creating scapegoats. Ever since, Brighton has remained the mecca among Mods. An annual meetup takes place every August, with many arriving on a Vespa or Lambretta.

The Mods were once treated as a national problem. Today, they’re an answer to one. Armed with an analog camera, Gen Z is on a quest of vicarious nostalgia. The new Mod and Northern Soul waves are only the beginning of the retro renaissance.