Felix Pilgrim: Exploring Identity Through Theatre, Religion, and Queer Portraiture

Exploring Identity Through Theatre, Religion, and Queer Portraiture: An Artist’s Perspective

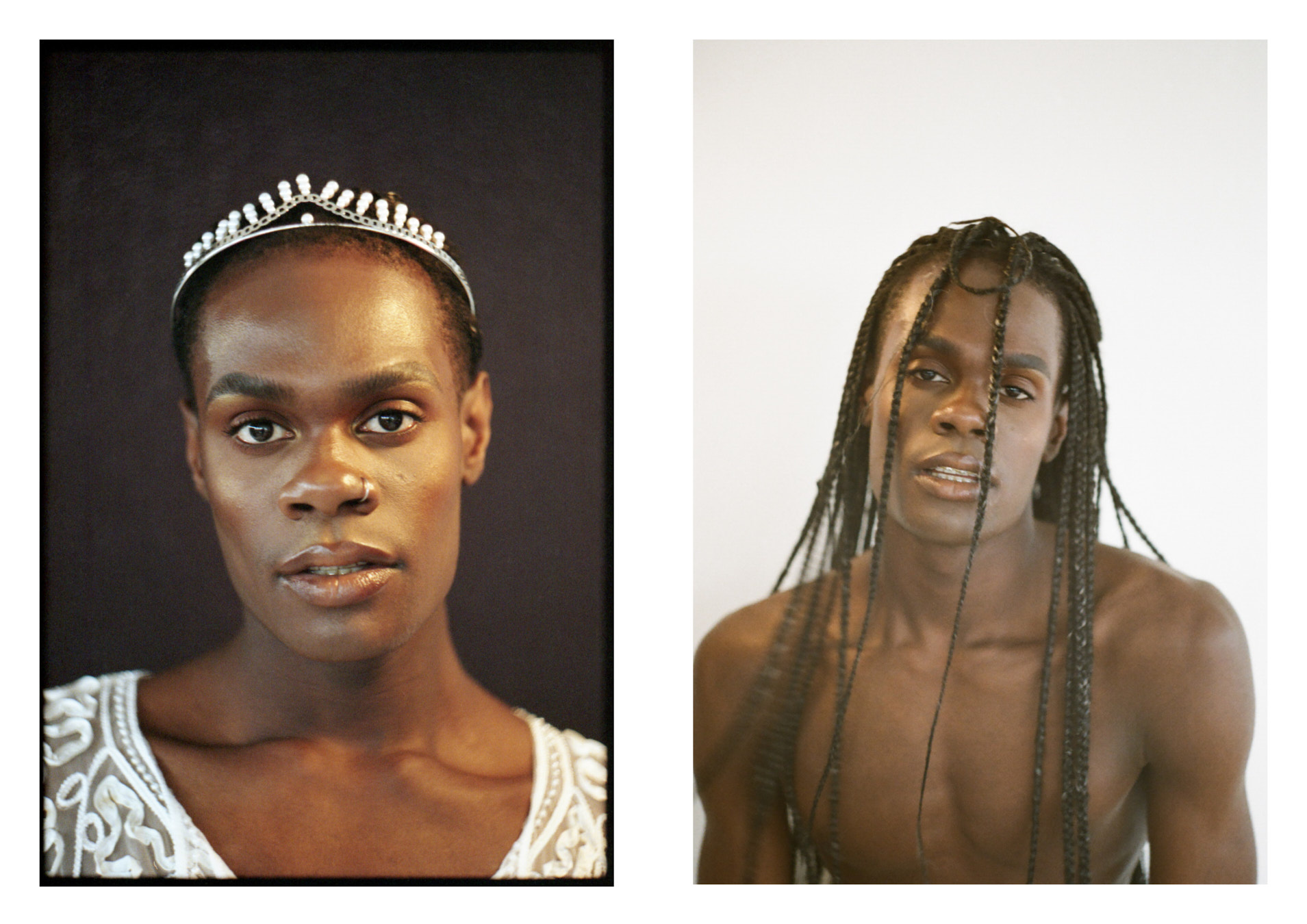

Felix Pilgrim approaches photography like a director, framing each image as a scene brimming with narrative and nuance. With an upbringing that blended theatrical storytelling with the quiet solemnity of religious iconography, he developed a visual style that draws from both realms, lending his portraits an almost cinematic resonance. In series like Hosts and Queer in the Country, Felix defies traditional perspectives on identity and intimacy, inviting viewers to see his subjects through fresh eyes. In this conversation, Felix reflects on his background, influences, and the philosophies that shape his approach to photography.

How has your background in theatre-making influenced your approach to photography, particularly in capturing portraiture and performance?

Growing up making and watching theatre trained my eye to look at the world in a specific way. The edges of a photograph (especially when they are rectangular) can look a lot like the edges of a stage. Doing theatre, I learnt that any image has a flow of energy moving through it. For example, positive forces are often associated with a motion travelling from left to right (much like the way most people read text), while figures can possess different levels of status and power depending on whether they are upstage or downstage from one another, and the same applies to composing a photograph. These topics came up when I led the workshop ‘Queer Tableaux: Camera as Audience’ at The Photographers’ Gallery last year.

I also started taking photographs of my friends who were actors, and it was amazing when I realised the camera could allow them to become a character or channel a quality that might not even be immediately obvious to the viewer of the photo. The camera allowed us to create what I like to think of as one-act plays. Julia Margaret Cameron was the first photographer I became obsessed with, and many of her nineteenth-century photographs are staged tableaux inspired by Shakespeare’s plays and Alfred Tennyson’s poetry.

I also love cinema and many of my images are, whether consciously or not, inspired by films and film trailers. When you think about it, trailers are often like a quick-fire sequence of a film’s best frozen images.

Can you describe how growing up in a religious household has shaped your artistic vision and the themes you explore in your work?

My dad is a vicar, but thankfully he never made our home feel overly religious. However, I did have to sing in a church choir between the ages of 7 – 13, so I was surrounded by religious art and iconography on a daily basis. In a lot of religious art, people’s eyes are closed, probably because they’re either dead or praying! I like photographing people with their eyes closed as it helps them return to a private internal space and potentially allows them to reveal the truest part of themselves. I also hope my portraits celebrate the person photographed, so perhaps I like turning them into these saint-like figures!

A lot of religious art uses the chiaroscuro technique, where angels and religious figures emerge from extreme darkness and are bathed in light. I drew upon this technique when creating my series ‘Hosts’ which focused on people who used Grindr around the time of the pandemic. I wanted to photograph them as simply as possible beside a window, the darkness behind them representing the past and the light from the window representing something more hopeful pertaining to the future. It felt like anyone using dating apps at this time might have been harshly judged, so I wanted to illuminate these people’s beauty, vulnerability, strength and dignity. After all, using technology to connect with others has more or less become a social norm and should be nothing to be ashamed of.

Your work delves deeply into the queer experience. How do you navigate and represent the complexities of queer identity through your photography?

It’s important to have an understanding of LGBTQ+ photographers from the past and present, and how their lives might shape their aesthetic language. I look up to figures like Hervé Guibert, Sunil Gupta, Peter Hujar, Yuki Kahara, Herbert List, Roman Manfredi, Ryan McGinley, Zanele Muholi and Wolfgang Tillmans, to name but a few.

What I thought about while creating ‘Queer in the Country’ is the complexities of someone being, feeling and/or identifying as queer even when they are not connected to other queer people or spaces. A lot of queer photography will depict people in bedrooms and nightclubs, and the undertone can often be sexual and hedonistic. When queer couples are photographed together, some photographers focus on their physical intimacy, or draw attention to their love for one another. Although these things are valid and important aspects of the queer experience, I wanted to remind people you can be queer and exist autonomously. From my own experience, it can be quite awkward to identify as queer when you’re not in a queer relationship or choosing to express yourself in an obviously queer way in terms of clothing or lifestyle. LGBTQ+ media often uses the phrase ‘queer community’ and I wanted to test what this phrase might mean when applied to queer people who are geographically distanced from one another.

In terms of representation, my images need to be as collaborative as possible. For this project, I wanted to photograph people in an area where they felt most comfortable and free to be themselves. An image can only say so much, so I have also included our conversations alongside each photograph, so that, as much as possible, they can say what they want to say using their own voice.

Felix leaves us with a powerful reminder that photography is, at its core, a dialogue between artist, subject, and viewer. His work reveals the often-overlooked complexities of queer identity, with each photograph serving to the beauty found in vulnerability and the power of authentic connection.