Seven Artists You Have to Know from Art Paris Fair 2025

Written by Jude Jones

Art Paris Fair 2025 felt something like an artworld terrarium. Nestled in the glass skin of Paris’s Grand Palais for its 27th anniversary, the prestigious fair’s return to the venue after three years of renovations and repairs, the affair worked as a microcosmic allegory for the art ecosystem: mossy webs of galleries, dotted crystalline with dewy artwork running the full gamut of modern and contemporary art, from Mirós and Picassos and Klimts to the prodigal progeny of emerging artists, snuggled deep and breathing in the fair’s hectic, life-giving soils.

Presenting a diversity of curated themes and topoi – a holistic focus on French figurative painting, selected by Amélie Adamo and Numa Hambursin; a demimonde of international works exploring themes of multiethnicity, multi-identity, and slippage chosen by Simon Lamunière; a first-time ever exhibition of French design and decorative arts; and a microscopic zoom on young galleries and young artists – Art Paris Fair 2025 felt revitalised in its ancestral home, dense with discovery and possibility. So discover we did, choosing seven artists you have to know from the fair.

Roméo Mivekannin Exhibited by Galerie Eric Dupont, Paris

When the West African Kingdom of Dahomey was conquered by French colonisers in the 1890s, its royal treasures were stolen and shipped Paris-wards and, for over a century, were held in the city’s museums until their restitution in 2021. This was a pivotal moment in African art history and the decolonise art movement, notably dramatised by Atlantics director Mati Diop in Dahomey (2024); however, it was also a pivotal moment in the family history of Ivorian-born, French-based artist Roméo Mivekannin (b.1986), an ancestral heir to these very treasures as the great-great-grandson of Béhanzin, the last king of a free Dahomey.

Mivekannin’s artwork reverses this extractive flow of artwork from Africa into the Western canon – seen elsewhere in the histories of Primitivism and Cubism – by repainting colonial photographs or icons of the Western art canon (Caravaggio’s Lute Player, Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa) as bold self-portraits, his own visage reproduced like a mask over each composition’s characters and figures. Rejecting however the European-developed mediums of the photograph or oil-on-canvas, Mivekannin indulges in new forms of representation and materiality as a means to reclaim their ancestral narrative, painting onto torn bed sheets and fabrics, first doused in herbal elixirs traditionally used in West African voodoo rites. If we have come to think of the work of art as sacred – as “auratic”, as once said Walter Benjamin – Mivekannin imbues his work with an older still spirituality, one antecedent to the white colonialist project and its failed attempts to pillage memory, sacredness, and art from his very ancestors.

Gaétan Vaguelsy

Exhibited by Galerie Polaris, Paris

All of the sitters of French-born painter Gaétan Vaguelsy’s (b.1992) works are his friends, the lads who used to skulk the streets of Paris with him, adorned in their armour of Nike and knock-off Louis Vuitton, looking for vagrant spots to graffiti and tag. Equally informed by this informal artistic coming-of-age as he is by his formal training at the MO.CO. Esba (École Supérieure des Beaux Arts Montpellier Contemporain) where he graduated with top honours, Vaguelsy’s oeuvre harmonises these two sensibilities into an unexpected middle-ground that is both classical and street, monumental and personal.

His work through this articulates a humorous yet grounded dialogue between art’s past and our present, implicating themes of masculinity, consumerism, and the quotidian into this discourse. In “Les Baigneurs” (2023), Vaguelsy’s friends supplant the nude female bathers of masters like Courbet or Delacroix, whose arcadian idyll is replaced by a Warholian landscape of commodity fetishism and product-placement objects – the LV bag, the Nike slides, the Pirulo ice pops on which his muses dine. Is this Vaguelsy simply representing his reality, or putting to paint the new sanctuary-spaces of human desire as once did Courbet and Delacroix, a sanctuary now saturated by brand names, childhood memories, and a simple yearning for connection and fraternity? Well, that’s for the looker to decide.

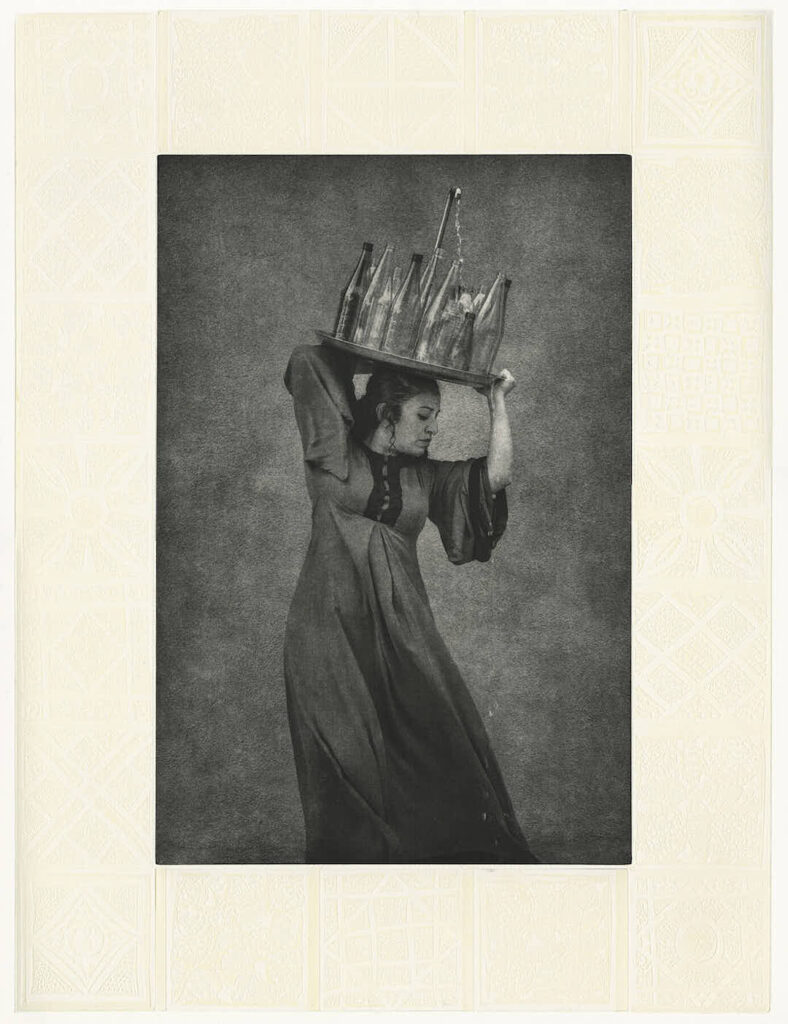

Sama Alshaibi

Exhibited by Galerie Esther Woerdehoff, Paris

Sama Alshaibi (b.1973) is an Iraqi-Palestinian multi-disciplinary photographer who makes of her body a monument to Arab female subjectivities in an image history marked by migration and war. Having been exhibited and awarded widely – she has shown at the 55th Venice Biennale, was made a Guggenheim Fellow in Photography in 2021, and is a Finalist for the Art Paris’s Her Art Prize – her self-portraiture nonetheless explodes beyond the bounds of individuality, representing a multitude of ambivalent archetypes, refracted through hermeneutic lenses of orientalist fetishism, colonial extraction, and paternalist Western feminism.

Presenting with Galerie Esther Woerdehoff, one of Paris’s premier photography galleries, her series Carry Over was produced using photography development and printing techniques contemporary to the height of the West’s orientalist photography fervour at the tail-end of the 19th century. However, Alshaibi turns the era’s modes of representation on their head. Represented with a constellation of orientalist props – water jugs carried on the head, shisha pipes, and palm leaves – she transforms the Arab female body from a compositional object to a defiant lifeblood: taking the form of a Rosie the Riveter-type in one photo, a mighty goddess in the next. The results feel something like a Cindy Sherman or Zanele Muholi: feminist self-portraiture that troubles both the discrete and bounded notion of the self and of femininity more broadly, sometimes more oppressively.

Killion Huang

Exhibited by Edji Gallery, Brussels

Killion Huang (b.1999) was one of the youngest artists displaying at Art Paris 2025. But his artwork, a mix of pastel-on-paper and oil-on-canvas works, each one ruminative and desirous, glorious and knotty entanglements of lights and bodies and reflections, were among the fair’s most mature. Trained first in China, then in New York, and inspired for this series by French Impressionism and post-Impressionism, it is these latter two influences that ooze heady and sticky from his canvases, which look something like a Peter Hujar photo repainted by Gauguin or a delirious and horny Monet.

Huang’s oil-on-canvas works are sober and haunting, catching fleeting moments of introspection and self-reflection which are amplified by his use of mirrors, windows, and other reflective surfaces in these works: a barely-clothed boy inspecting his own body in “Cumulonimbus” (2025); another – back tattooed by suction marks from cupping therapy – gazing through a window in “Sanctuary” (2025). Meanwhile, his pastel-on-paper works are spontaneous and kinetic, yet gesture to similar themes of cagey contemplation and burgeoning eroticism through their subjects, from animals in cages or torsos in Versace underwear. Huang, as an artist, interrogates a postmodern queer subject with a modernist’s toolkit, and the outcomes are extraordinary.

Barbara Navi

Exhibited by Galerie Valerie Delaunay, Paris

French-born artist Barbara Navi (b.1970) glitches the world of figurative representation. Creating tableaux saturated in art historical and iconographical references, her methodology nonetheless distorts referentiality and representation to the limits of legibility, leaving only uncanny pixels and blurs like a tab of acid placed on the tongue. Uncanny, as in the Freudian sense of something feeling familiar yet different: unheimlich in the psychoanalyst’s native German, or “unhomely.” Because Navi’s paintings carry this trace of the almost-familiar, of the intimate stranger, a Skinamarink sense of waking up in a house you know is yours, but that is no longer within your cognitive grasps.

Coming-of-age among an iconoclastic generation of French artists in the aftermath of ’68 with an in-born sense of institutional distrust and rebellion, her subjects are therefore incoherent yet united in this disorder: in “POW ! BLOP ! WIZZZZZ !” (2025), a Zorro-masked child with the air of a Korine-movie star screams triumphantly; in “Feux de bengale” [“Bengala Flares”] (2024), a group of ghostly figures convene on a table, joined in the bottom-right corner by an appropriation from a Poussin-esque pastoral. Where these unite in her cosmology however is just as cryptic as her means of rendering said cosmology whole.

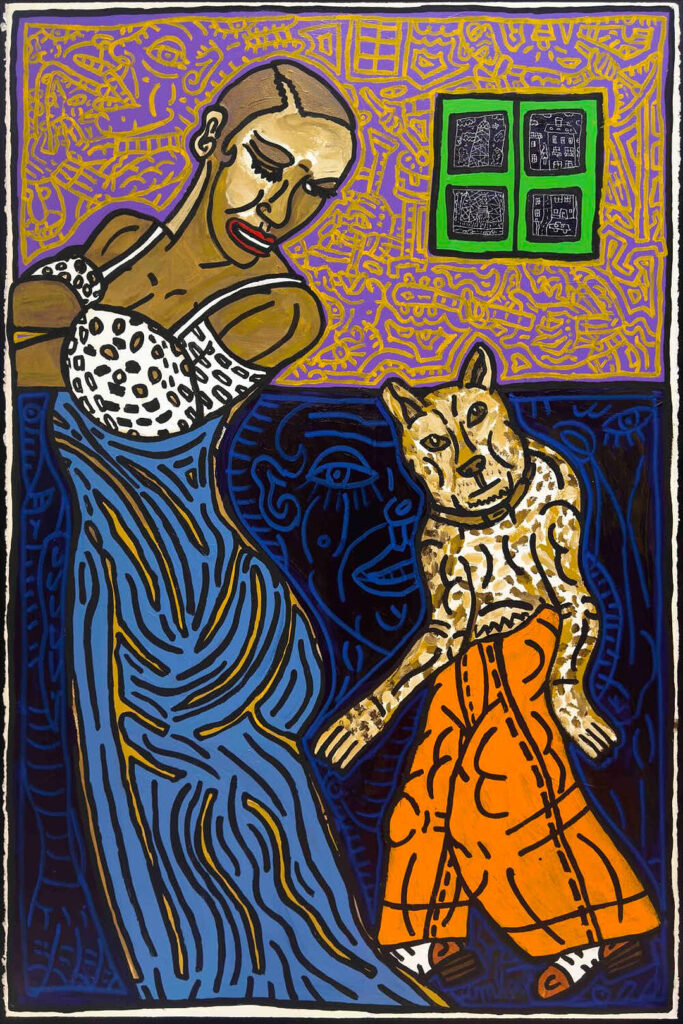

Robert Combas

Exhibited by Strouk Gallery, Paris

One of the figureheads of figuration libre (“free figuration”), a French spin on American Bad Painting that metabolised traces of street art and comic-book caricature into its figurative schema, Lyon-born Robert Combas’s (b.1957) work is simultaneously singular and familiar, conjuring cues from the likes of Basquiat and Haring, whose works the artist was often internationally displayed alongside during figuration libre’s 1980s apex.

Articulating a countercultural episteme that elected idols, against a whitewashed art establishment, of Black and African-American icons – Josephine Baker in one painting, Louis Armstrong in another – his paintings nonetheless resist portraiture and settle someplace else, a labyrinthine schema of metaphysical representation in which bodies jostle into multitudes, block colours and kinetic lines coalesce into pareidolic faces, and dimensionality and space lose any stable hold. A someplace else, a liminal nowhere divvied between, perhaps, the subliminal dreamscapes of Surrealism, the desirous materiality of Pop Art, and the enfant terrible impulses of shock art: Combas, a self-described “greedy man”, indeed metabolises all.

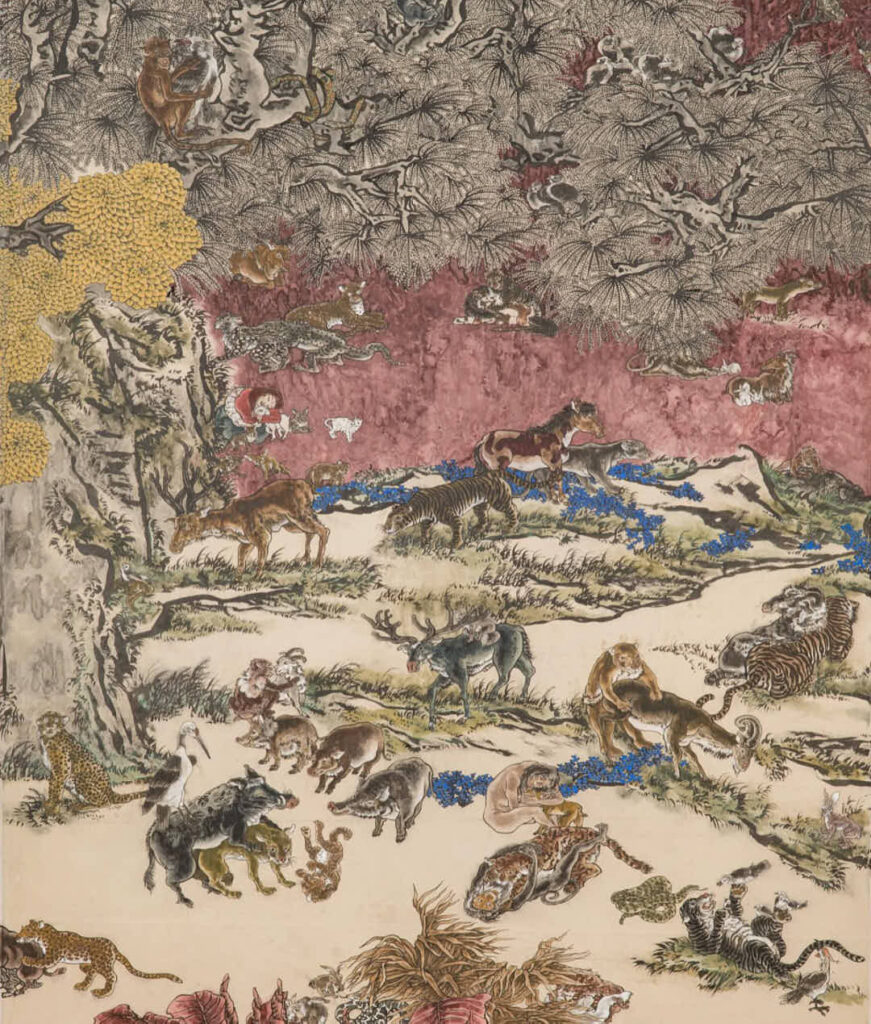

Yang Jiechang

Exhibited by Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris

Yang Jiechang (b.1956) is a titan in Chinese contemporary arts, with work displayed at the Centre Pompidou, the Palais de Tokyo, the Venice Biennale, and the Metropolitan Museum of Arts. Secretively trained in traditional Chinese media by his grandfather during Mao’s Cultural Revolution, he instinctually both these techniques and their histories with Western philosophies and Western avant-garde aesthetics – above all else those of German Romanticism recently revitalised in Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu, with all its yearning for spiritual nourishment and human symbiosis with the natural world.

Presented at this year’s fair by Paris’s Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, which this year celebrates a century since its founding, exhibited was his monumental (almost 20m across) and ludic landscape, Tale of the 11th Day – Red Autumn (2014-25). Referencing in its name Boccacio’s Decameron – a series of 100 tales told by 10 characters in a country villa, secluded from the Black Death’s ravages – the orgiastic panorama nonetheless presents a world of egalitarian carnality and libido, of interspecies sexual encounters unbound from prejudice and united in an indiscriminate, worldbuilding network of desire. Only away from human-made isolationism, narratives, and egoism, Yang appears to suggest, can true pleasure reign.