Pascal Sender: The Artist Rewriting Art History

Written by Joshua Beutum

Pascal Sender is a Swiss artist working at the intersection of physical and digital mediums. In his new solo exhibition at Saatchi Yates Gallery, he explores everyday “states of flow” through post-futurist depictions of subjects fully immersed in their day-to-day activities. In a startlingly restless combination of oil, graffiti-style airbrushing and augmented reality, he reveals the digital era to be one of dynamism, immediacy and movement.

Interviewing Sender, I can’t help but identify with his playfulness. A playfulness that extends from his outrageously chaotic, almost jittery compositions into our otherwise quite ordinary discussion of digitality, mixed-medium painting and augmented reality. His unabashed sense of irony and an equally tongue-in-cheek perspective on his work set the tone – after our conversation, he jokes that he’ll ask a “simulated copy” of himself “strange things to check all the safeguards are in place”.

This humour is unsurprising for Sender, whose portfolio is in equal parts an homage to 2000s-era Myspace and a post-structuralist critique of order and functionality in the digital age. With a logo that takes the form of his delightfully whimsical, squiggly-lined cartoon doppelganger, Sender’s embrace of hyper-online sensibilities and digital aesthetics should not be mistaken for frivolity, much less meaninglessness.

Highlighting the increasingly blurred line between the human and mechanical, Sender creates post-futurist scenes depicting everyday characters immersed in their day-to-day activities, in what he calls “states of flow”. Suspended in fluid motion, a skateboarder performs a kickflip, a guitarist strikes a chord, a receptionist talks on the telephone.

Painting with a unique restlessness that seems to vibrate off the canvas, he contemplates a cultural climate fuelled by immediacy, momentum and dynamism.

In a new exhibition opening at Saatchi Yates, Sender reframes canonical artworks by introducing decidedly modern elements. Among these references is Umberto Boccioni’s Dynamism of a Cyclist (1913), which Sender reimagines as a series of electric vehicles – a scooter, a dune buggy, a jet ski, and a Picasso-style guitarist, morphed into a rockstar whose strums spread lightning in waves across the canvas.

In evoking canonical works from a period marked by both grave unease over the rise of fascism and dizzying technological progress, Sender underscores the cyclical nature of human civilization, teetering between innovation and destruction. Though Boccioni’s bicycle has become an ultra-modern electric jet ski, it still embodies the existential agitation that he sought to capture over a century ago – a tension that, in the context of rising authoritarianism in Europe and beyond, feels especially topical.

“My references are handled similarly to an AI system,” Sender tells me, referring to his practice as a means for processing the flurry of pictures he encounters daily. “I have an overload of images and interpretations I see in movies and art museums, and I’m just trying to remember them, and even harder to remember them in a painterly way.”

Sender’s instinctive approach is also apparent in his choice of mediums. Building on an initial layer of oil paint, he draws impulsive, freehand lines with a graffiti-like air compressor, creating a contrast between the traditionality of classical techniques and the immediacy of street art. Afterwards, he works on his paintings in augmented reality, using the physical “sketch” as the basis for further development in a new dimension.

“I don’t have an answer to why I use these mediums,” he tells me. “I try to be fearless and use them to achieve certain effects. I’m interested in the technical aspects of the mediums,” he continues, “but I’m more focused on output and creative momentum.”

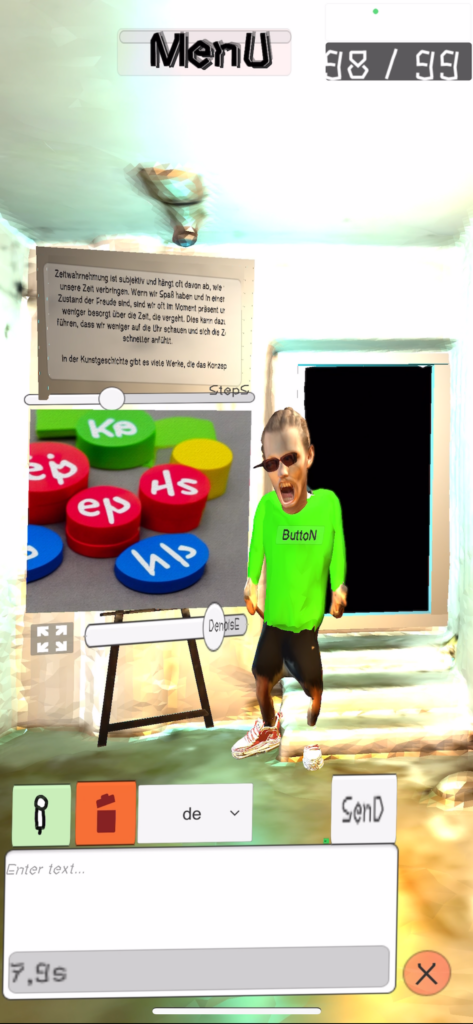

But where Sender pushes the boundaries of conventional art the most is in his use of augmented reality. Moving beyond commentary on the integration of humans and technology, Sender invites the audience to experience this relationship through his hand-coded app. Through their phones, viewers can watch Sender’s characters can jump off the canvas into a three-dimensional realm where they move, transform and interact with the user.

There’s also a copy of the artist that, for lack of a better phrase, lives inside the app. “It’s a programmed self-portrait,” Sender tells me, “I tweaked whatever I could, so he responds to questions like me, he can paint with prompts and then respond like I do”.

The portrait has also been programmed to speak with his voice. “It’s a vocal clone.”

For Sender, using augmented reality offers another advantage: “It gives me the freedom of not finishing a work, even when it leaves my studio. I hope the user feels this flexibility when they open the app and find an updated version of the piece.” He continues, “It’s like the piece is aging, or that there’s an interactive component tied to time.”

True to form, there’s also an element of irony in Sender’s use of this technology. In an increasingly social media-driven landscape, where going to a gallery is only as valuable as documenting that you went to a gallery on Instagram, Sender is embracing the camera as an intrinsic part of the experience. While some may resist this digital mediation of their art – or pander to it – Sender is in on the joke.

“I’m joking about how people look at the painting through a phone,” he laughs, having incorporated the camera directly into how we engage with his work. “So much has already changed, and I’m reacting to this new environment where phones are everywhere by making a situation where I ask for it.”

When I ask what he hopes audiences take from his new exhibition, he simply says, “A smile.”

Pascal Sender’s new body of work is on display at Saatchi Yates from 7 March to 11 April.