A Horse With No Name: Sasha Elage, Addison Rae, and the issue of the ‘Reference’

Written by Lily-Rose Morris-Zumin

Edited by Jude Jones

When Addison Rae’s new video for “Headphones On” was released, it appeared as an indie sleaze-infused brush with nostalgia—blurred eyeliner, dreamy synths, and a soft-focus ache for something lost. Styled like a fever dream of Y2K aesthetics and filtered through the lens of longing, the video unfolds like a diary entry written in glitter gel pen and heartbreak. Gone is the influencer sheen of Addison’s past; in its place, a fantasy world, both intimate and surreal.

The strength of the visual direction was immediately recognised. Praise flooded the comments: ‘The people behind the creative direction deserve their flowers,’ wrote one viewer; ‘The metaphor of escaping into her imagination is so beautifully done, so creative,’ said another. Aesthetically, the video succeeds. It blends nostalgia with cinematic flair to build a distinct, emotionally-charged universe.

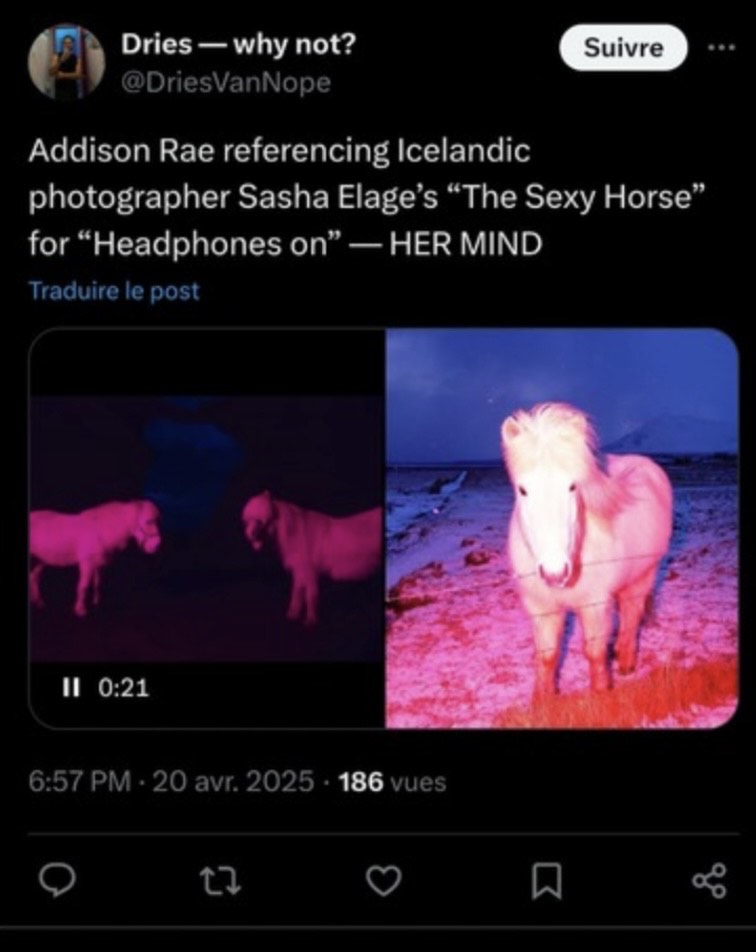

But for French artist Sasha Elage, the escapist world surrounding Rae felt not only fantastical but uncanny.

Post-release, Elage’s inbox began to fill rapidly. Friends, followers, fellow artists: all saying the same thing. They’d seen this before. Complete with pink horses emerging from an Icelandic, near-featureless dreamscape, the imagery bore an eerie resemblance to Magic Island, Elage’s own Icelandic photo series, which had long been circulating through gallery spaces and social media feeds.

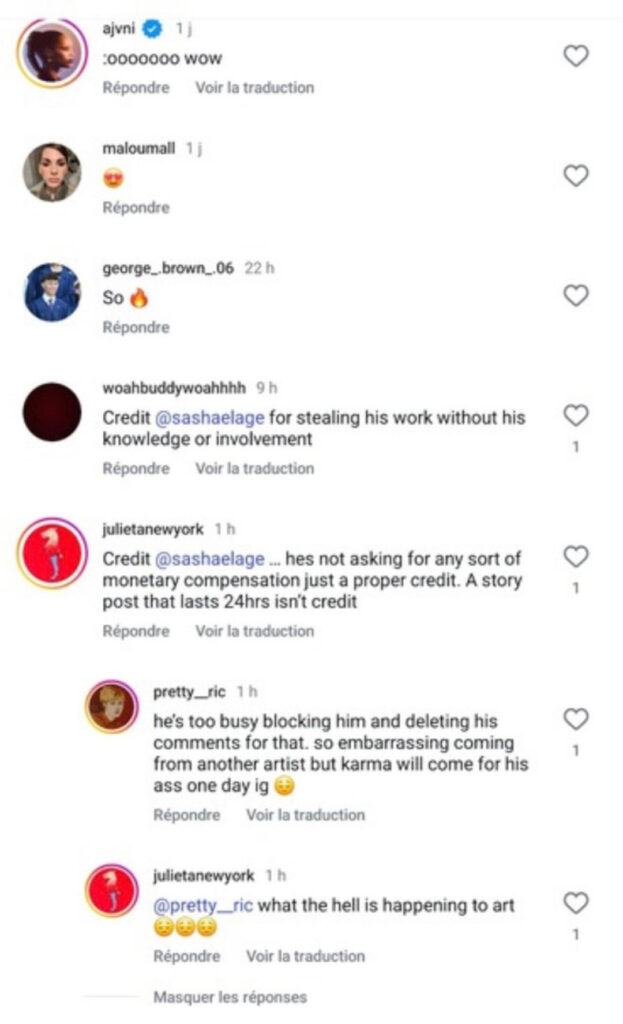

‘I woke up and my phone was dancing,’ he tells me. Hundreds of people were sending the same message in great waves: Did you direct Addison Rae’s new video? Why are you not credited? The resemblance was too precise to ignore. ‘I was watching my own work recreated,’ Elage says. ‘Beat for beat.’ Eventually, Rae and her team acknowledged that Elage’s work had been used as a “reference” but only in a fleeting 24-hour Instagram Story. No formal credit was given.

As writer Viktoriia Vasileva puts it in Reference Board Final Bosses and the Irony Epidemic, ‘what the public discourse refers to as a reference is actually just a blatant copy of something ripped out of its original context for the sake of visual aesthetics.’ It’s not homage, it’s harvesting.

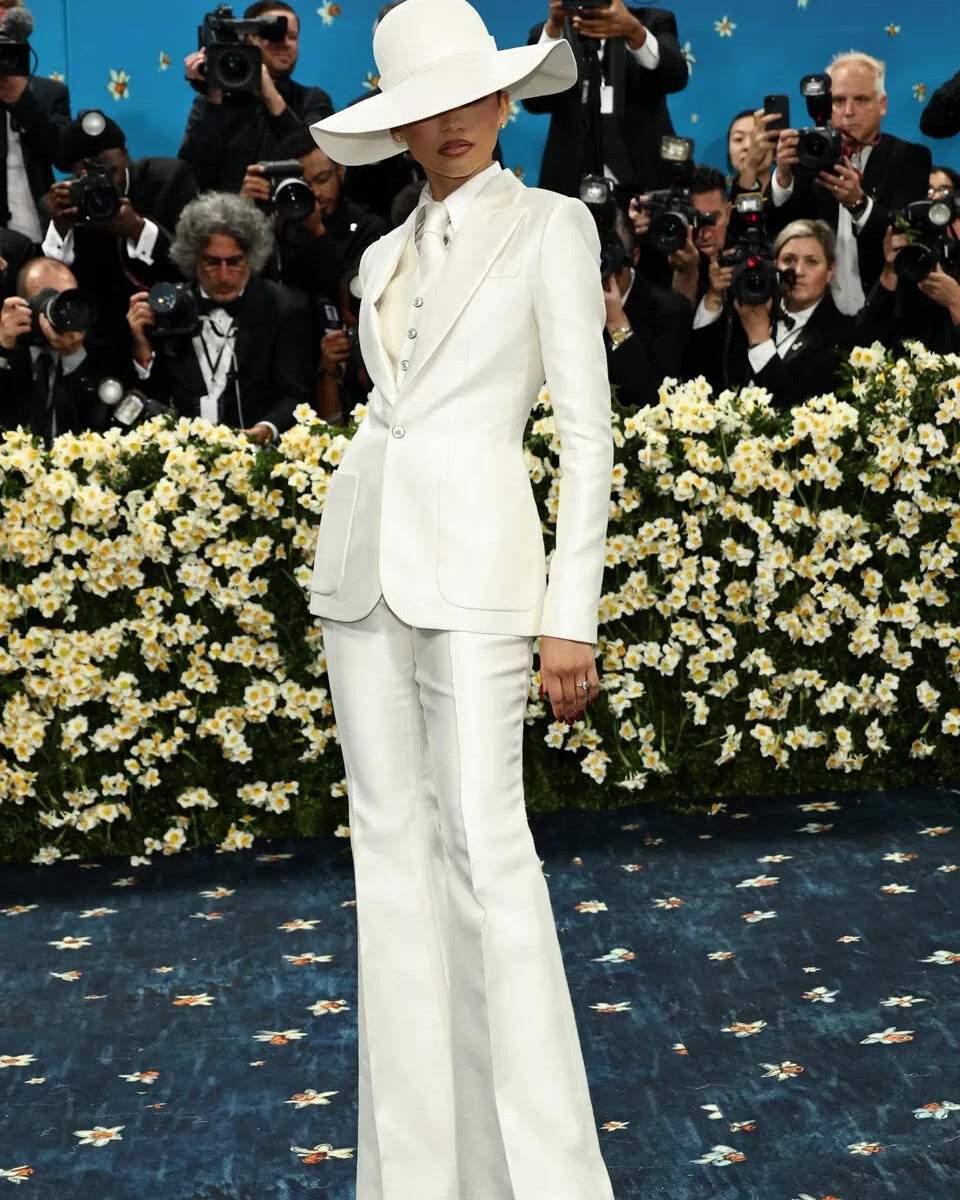

This is evident even beyond Elage’s work. When Rae’s horses disappear and she returns to the ‘real’ world, the déjà vu lingers. There she is, straddling a coin-operated horse outside an Iceland supermarket, a striking rehash of Jennifer Connelly’s ride in the 1991 film Career Opportunities, where a few 20-somethings get trapped overnight in a supermarket. The eroticism, the choreography, even the framing. It’s less a visual nod than a direct quote, just with gauzy lighting and glossier lips.

The resemblance raised increasingly relevant questions about credit, artistic boundaries, and the space between influence and replication.

Sasha retells the moment of realisation for me. Behind him, two large prints of his work hang on the wall, horses flanking him just as they flank Addison Rae in “Headphones On”. That detail, he explains, made the connection impossible to ignore.

‘I looked at the video, and for the first 10 or 20 seconds, there’s not much happening. She’s just walking in the streets,’ he says. ‘Then, when the music drops, my two horses appear.’ Later, he tells me, the horses show up again, each time seeming to anchor the video’s narrative. ‘They appear with her face overlaying them in a montage. It was done so smartly, in a way that associates the drop in the music with this specific imagery.’

He pauses, seemingly still processing the surrealism of it all. ‘It wasn’t just filler images. They were key visual moments… timed so perfectly with the drop of the chorus that they grab your attention, almost like a visual hook.’

The video, released in April 2025 and directed by Mitch Ryan, has since garnered 2.7 million views on YouTube. Ryan, who also collaborated with Rae on her February 2025 release ‘High Fashion,’ has worked with artists like Rosalía and been involved in high-profile campaigns with brands such as Nike and Glossier.

In “Headphones On,” Ryan distills Elage’s carefully crafted Icelandic tableaux into a looping pop‐promo motif. The result effectively commodifies his vision, turning a once‐singular ‘aura’ of light and place into a disposable branding device that extends past this video to also be used in promotional material.

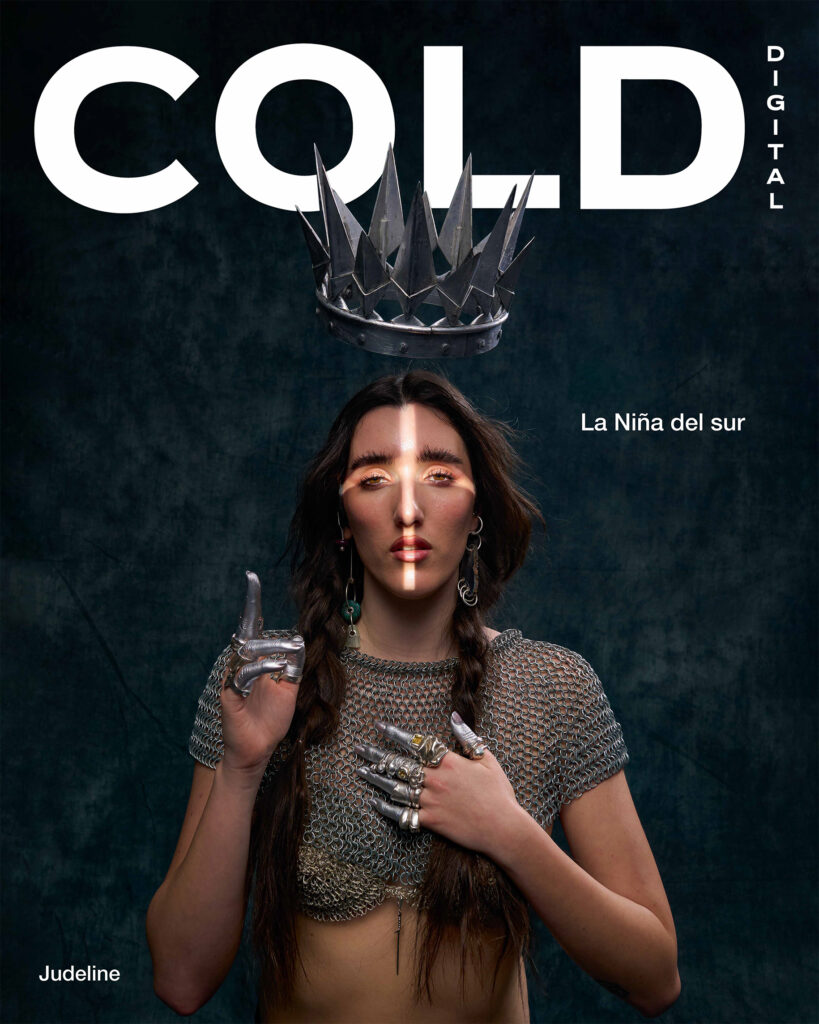

For Elage, photography is a form of transformation. Not documentary, but alchemy. ‘I don’t want to photograph a tower, a monument, or something that’s already beautiful. That would feel too easy. I want to go looking for beauty in places where it’s not usually found.’ So when he finally made it to Iceland, a place he’d dreamed of visiting for two decades, he wasn’t chasing the aurora borealis or shooting National Geographic-style panoramas. ‘Those photographers have done it well already,’ he says. ‘I wanted to make something new.’

His comment about wanting to ‘make something new’ feels newly tinged with irony. I ask what happened once people began tagging him under Rae’s video.

‘That’s when Mitch Ryan reached out to me. He said, “Sorry, I didn’t know you were a living artist! Hopefully this will point people in your direction.’” He laughs. ‘With no credit? How could this possibly point people in my direction?’

Roughly ten hours later, Addison Rae followed Elage on Instagram. ‘She messaged me saying, “Oh my god, I love your work, I love what you do. I didn’t know who you were, but your work was everywhere on our mood board.”

The production involved a large team, flown out to Iceland alongside a pop star. Their mood board, Elage tells me, would have been put together with a team of professional directors and photographers. But when it came to identifying the artist behind the central imagery, they couldn’t seem to make the connection. ‘My work has been published in international magazines, viewed millions of times on TikTok and Instagram. If you type ‘red/pink horse’ into Google or Instagram, I’m the first result. It felt like they just ignored it.’

After this initial exchange, Addison posted an Instagram story naming Elage as an inspiration for the video. But, as he points out, stories disappear after 24 hours. ‘There’s no way that can be considered proper credit,’ he says. ‘It’s not good legally, ethically, or morally. It’s just wrong.’

What followed, he suggests, was even more troubling. ‘After that, they started deleting the comments. People were tagging me under the video, and then those comments started disappearing.’ This, from an artist with over 100 million followers, whose video and accompanying promotional campaign Elage says has ‘replicated, mirrored, and directly incorporated elements of [his] work.’ Things escalated when he found himself unable to view the video at all. ‘I had people messaging me saying, ‘The video’s still up, but you can’t see it anymore.’

In his final attempt to resolve the situation, Elage reached out once more. ‘Please, just acknowledge it publicly, and I’ll be happy to do photos for you, anywhere you want. I have a clear vision. I could make the most beautiful portrait of you. I could put you on a horse in a fjord and we could create something magical.’ He smiles, then shrugs. ‘But it’s been a week and a day, and she still hasn’t replied.’

In the meantime, the internet hasn’t gone quiet. ‘People are still commenting, journalists are reaching out. This is very wrong. This isn’t good. This is my life. I’ve built everything around photography, and Magic Island is my magnum opus. I’m still working on it. And ironically, in three weeks, I’m going back to Iceland, invited by a production company making a documentary about me, to shoot the final chapter of the series.’

‘And now an artist takes it, shows it to millions of people, and there’s no way they’ll know it’s mine. For them, it’s Addison Rae. People are praising it as so creative, and the team is claiming they didn’t use AI, which is just… surreal.’

At this point in the interview, I’m relieved I asked him about his work first. The language used by Rae’s team, by commenters, even by Sasha himself, at times, is so similar that the repetition becomes impossible to ignore.

Elage slows. ‘Photography is my life,’ he says. ‘It’s everything that matters to me. My love and hunger for photography is insatiable.’ He exhales. ‘I still feel like I haven’t even started. I’ve made 1% of the ideas I have in my head.’

Elage’s experience, though deeply personal, reflects a broader truth in today’s entertainment industry: the line between homage and appropriation is razor-thin, and artistic recognition can easily be swept away by the currents of mass consumption. As Addison Rae’s video continues to rack up views, the question remains: Who owns the creative identity of a work?

In his 1935 essay, Walter Benjamin argued that mechanical reproduction strips a work of its “aura”, its authenticity, its presence in time and space. In the digital age, that idea feels more relevant than ever: a vision can be replicated, remixed, or rebranded in seconds, often without credit or context. Which vision gets to echo across the world, and whose is drowned out in the noise of the algorithm?

To name this phenomenon is not to decry the existence of reference, but to question how, and by whom, cultural images are consumed.

Fredric Jameson’s concept of pastiche offers a useful lens through which to view this situation. Pastiche, as Jameson defines it, is a style that mimics without meaning, a collage of fragments pulled from various sources but lacking any real emotional or historical depth. It’s the art of replication for replication’s sake, something that reflects, but doesn’t engage with, the original. In a world where everything is remixed, shared, and sold at lightning speed, Elage’s work is swallowed whole by the pastiche machine, commodified and diluted until its unique essence disappears into the background hum of content consumption.

The irony here is stark: Addison Rae’s video is undoubtedly creative, showcasing her talent. But in appropriating Elage’s work without proper acknowledgment, it attempts to distill his art into a flashy, digestible bit of internet culture. This isn’t homage; it’s the hollow imitation that pastiche represents: a facsimile, a shell of something once full of personal narrative and meaning.