Seeing Double: Why Are We Seeing So Many Doppelgängers On Screen?

From “The Substance” to “Severance”, we have become obsessed with the split psyche.

Written by Valeria Berghinz

In Germanic folklore, to see one’s double is to be assured that death is near.

The doppelgänger, both spectral and symbolic, has haunted the human imagination across centuries, manifesting as a harbinger of doom or a fractured reflection of the self. From the Nordic myth of doubles as future echoes – déjà vu rendered flesh – to Fiji’s folklore of shadow-selves harbouring sin while their watery counterparts carry virtue, the twin-image occupies a liminal space between superstition and existential dread. The shadow in particular is a key figure in the international compendium of anxious doublings, along with one’s image in the mirror and the painted portrait.

In his seminal work The Double: A Psychoanalytic Study (1914), Otto Rank traces this folkloric tapestry in an assertion that the figure of the double is not just a relic of the mind but a fertile, recurring archetype. This shared fascination with the twin-image persists, evolving through oral traditions, literary movements, and, finally, cinema.

Today, the archetype’s contemporary potential is more than evident. Only in the past month, The Substance and A Different Man have competed at the academy awards, Severance has dominated TV discourse, and Mickey 17 has been released to cinemas internationally. But what do these doppelgängers tell us about our current identity anxieties?

The key lies in the figure’s cultural past, providing a framework through which we may understand this contemporary zeitgeist.

In the Gothic tradition, the doppelgänger emerged as a literary cipher for the psyche’s darker alleys, perfectly suited to the Freudian preoccupations of the 19th century. An iconic novel which delineates this interest is Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, where the tension between the ego (our polished, public face) and the id (our primal, unfiltered instincts) refracts into two warring selves. In stifling Victorian society, the ‘freeing’ act of doubling the otherwise repressed id created an ugly, rampaging monster – at least in the case of Mr. Hyde. But Stevenson did not set out to write a tale of morality, rather a psychological investigation of the complex social realities which harbour dangerous instincts within good men.

Whether a doppelgänger appeared by mystical means (The Double), scientific experimentation (Frankenstein) or dubious familial ties (The Devil’s Elixir), interest usually lay in this separation between the social and the antisocial, warring psychological factions. So much so that the reality of the double often came into question: is there truly a doppelgänger, or are we being manipulated by an untrustworthy narrator?

Strikingly, the question of narrative manipulation evades our contemporary examples. The movies and show in question, instead, eschew Gothic moral duality in favour of a sterile, scientific framework. In these narratives, the doppelgänger is no longer an existential threat, an uncanny shadow of repressed desires or fears. Instead, it becomes a tool – something to be commodified, exploited, or endured in service of a larger system. The doppelgänger’s purpose shifts from personal revelation to economic survival, reflecting the anxieties of a workforce-driven, hyper-capitalist society.

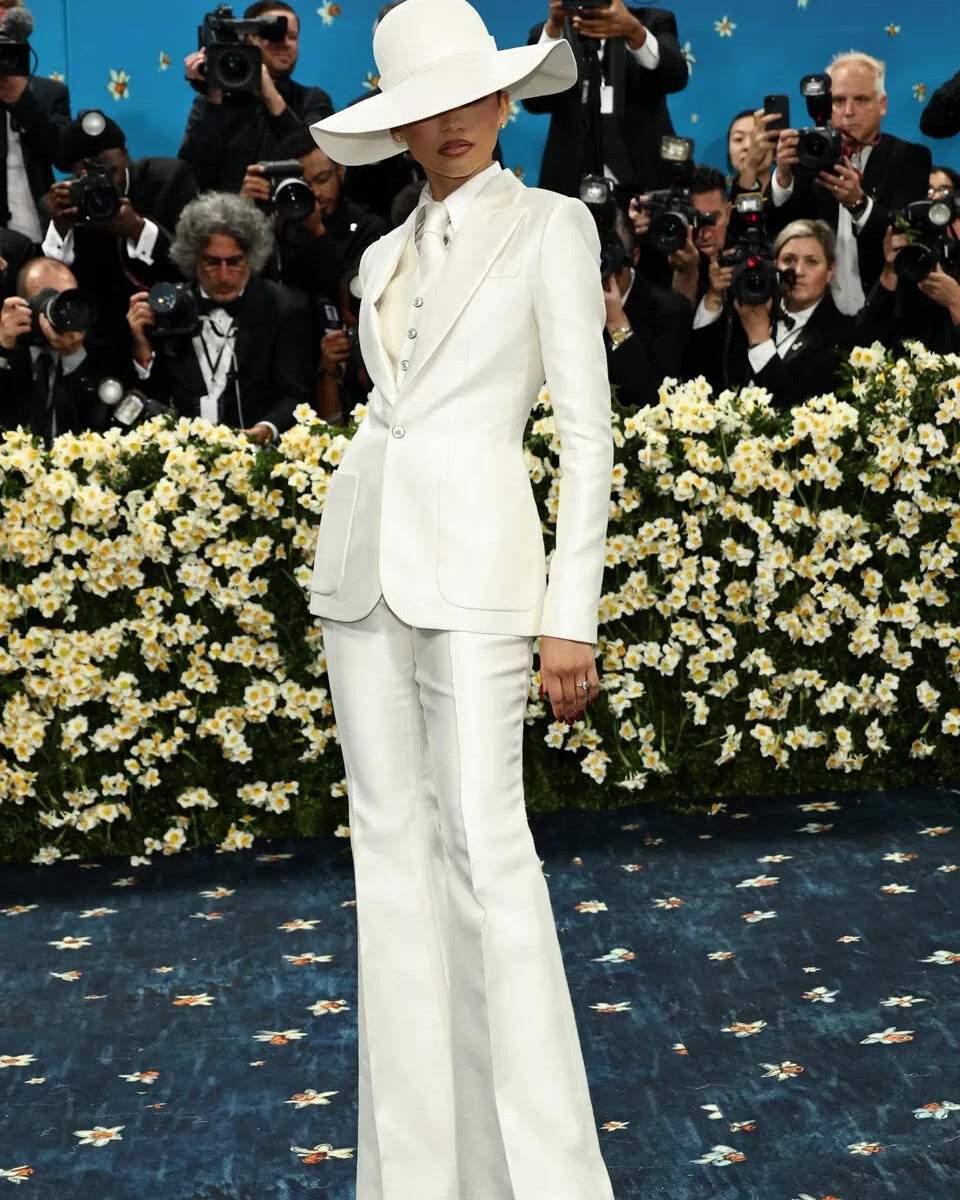

In The Substance, the doppelgänger Sue (Margaret Qualley) – a “younger, more beautiful, more perfect” version of aging starlet Elizabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) – gurgles into life through the injection of a black-market drug. The desperate choice to undergo such a traumatic physical transformation is triggered by Elizabeth’s 50th birthday and subsequent firing from her aerobics TV-show. In a marketplace where the sexualised female body defines economic value, Elizabeth’s identity as an older woman is a liability. Undergoing the violence of creating a double reflects a grim adaptation to a social order that commodifies and discards women based on their adherence to unattainable standards of beauty.

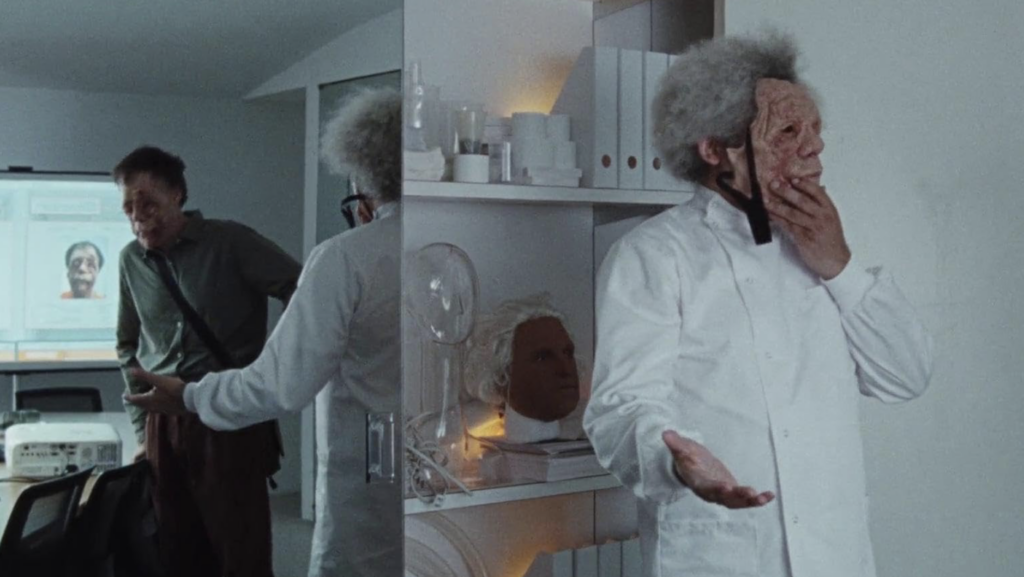

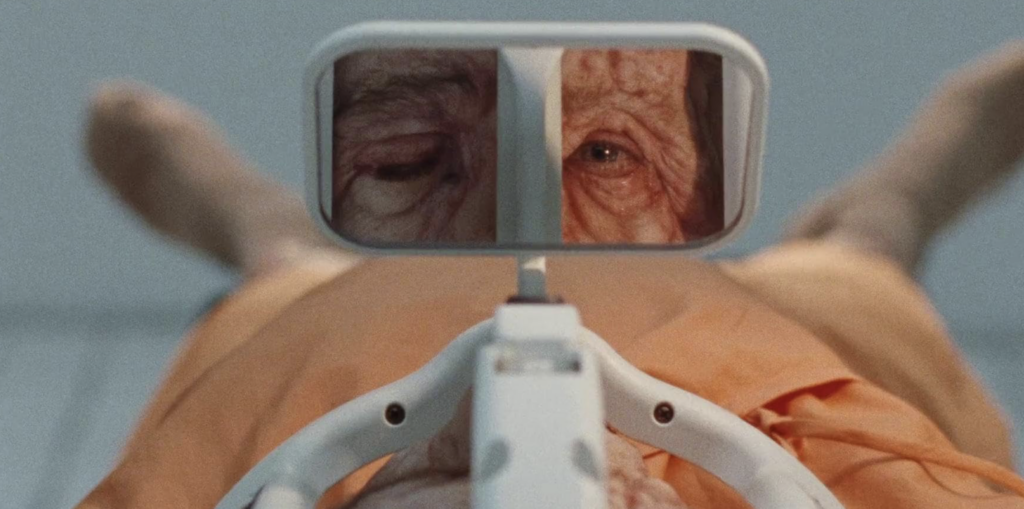

A Different Man follows Edward (Sebastian Stan), a man with neurofibromatosis who undergoes a painful experimental medical procedure to shed his facial disfigurement. As he attempts to navigate the professional and romantic successes of his new life, a double of his pre-treatment self appears in his social circles. Oswald (Adam Pearson), the quasi-mystical doppelgänger, waltzes through life with a confidence and ease that Edward could never achieve, ‘healed’ or otherwise. Through this surreal and disquieting dynamic, the film interrogates the relationships between identity, beauty and society. Which is shaped by the other, and where does our agency lie?

In the newly released Mickey 17, the doppelgänger emerges once again through the lens of scientific innovation. The titular Mickey (Robert Pattinson) signs up to work as an “expendable” aboard a spaceship bound for distant colonisation, driven by the desperate need to escape his earthly debts. This labour entails repeated deaths in the name of science and the subsequent re-printing of his body, a violent and undervalued role within the capitalist schematics of this imperialist project. Mickey is particularly naïve and easily manipulated, making him an easy subject for exploitation, his body and life commodified in a system that values him only for his disposability.

Contract doppelgängers are also featured in Severance, where the enigmatic conglomerate Lumon enforces a medical procedure that physically enacts the work-life divide. Through this process, employees’ consciousnesses are split into two distinct identities: the innie, confined to the workplace, and the outie, free to live life outside of office hours. Mark (Adam Scott), our protagonist, undergoes severance as a desperate escape from his grief, seeking to carve eight hours a day out of his depressive cycle. On the other end, the procedure traps the innie version of each employee in a sterile purgatory of endless, meaningless computer work and surreal corporate culture. Severance sheds light into the absurdity of the capitalist work-model, where our very consciousness is a commodity to be exploited in support of a meaningless capitalist structure.

It is hardly surprising that contemporary media is drawn to the scientific dimensions of the doppelgänger narrative. While not a wholly new concept, today’s portrayals diverge significantly from their literary predecessors. We are no longer dealing with a single mad scientist’s hubris, but the systemic evolution of a scientific-industrial complex encouraged by productivity and exploitation. Against the backdrop of an ever-expanding marketplace for bodily modifications – think the vertiginous rise of Ozempic and its weight-loss capabilities – the medicalised settings of these narratives reflect a culture increasingly obsessed with optimizing the human body.

Another departure from our literary past is the intent behind the creation. These contemporary stories portray doubles born of desperate attempts to align with the status quo rather than temptations to stray from it. Whether grappling with age, deformity, intellectual limitations or depression – universal but stigmatised human experiences – the decision to endure such physically violent transformations mirror our shared desperation to align with impossible societal norms.

The alignment demanded in these narratives is not simply a matter of personal choice but one incentivised by the workplace and the economic market of science. This dynamic reveals a darker truth: the relentless pursuit of acceptability, stretched ever further from the norm, serves as a profitable industry. It feeds on our collective desperation to conform and please, transforming the act of reconciling the self with societal expectations into a commodified cycle.

What we learn from The Substance, A Different Man, Mickey 17 and Severance is that we have already forced our identities to be doubled in an attempt at survival. Our authentic selves – marginalised and insecure – are commodities, exploited in the pursuit of a better, more efficient doppelgänger tailored to societal demands. But our contemporary writers and directors ask us to stop for a minute and ask ourselves: who ends up profiting in all of this?