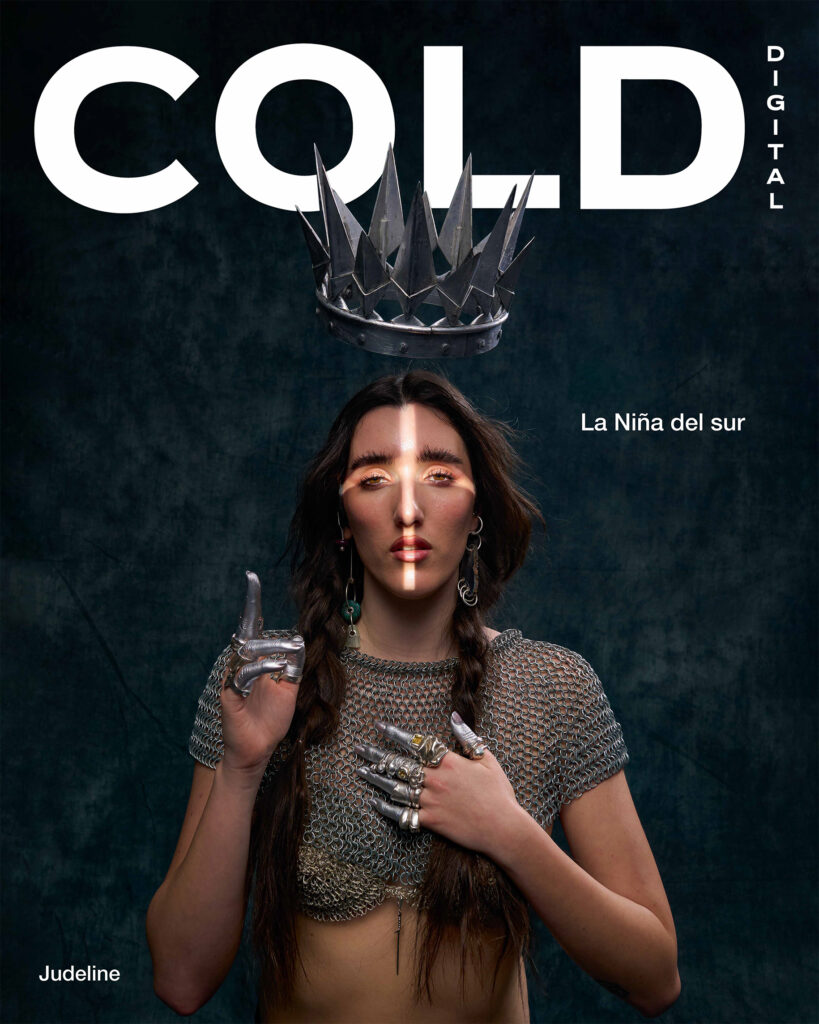

“I Wanted It to Sound Like a Fabulous Woman — or an Antidepressant”: Inside Sienna Murdoch’s Gelatinous World of Geline

Written by Penelope Bianchi

Edited by Beata Li

Glistening, gelatinous, and faintly perverse, Sienna Murdoch’s sculptures walk the line between seduction and revulsion. Crafted from Geline — a bio-material of her own making, derived from seaweed extracts and vegetable polymers — these flesh-like forms slump, sweat, tremble. They shimmer with the familiar appeal of jelly, but resist easy classification. Still, they never feel inert.

Murdoch’s work emerges within a broader cultural resurgence of jelly as an artistic medium. Once a symbol of post-war domesticity and suburban aspiration (think Jell-O molds and 1950s dinner tables), gelatin has been reclaimed by contemporary artists as a tool for exploring gender, identity, and bodily politics. From historical Regency-era centrepieces to today’s queer, internet-fuelled jelly artists, the medium has always oscillated between spectacle and subversion.

However, unlike many of her peers, Murdoch’s relationship with jelly is not a particularly nostalgic one. ‘One of the reasons I called it Geline was because I wanted it to sound like a fabulous woman or a global conglomerate, like LVMH — or even an antidepressant,’ she explains. Geline is designed to fail, to melt, to respond; it pushes jelly’s aesthetic associations beyond culinary kitsch, asking what it means for a material to be both seductive and grotesque, vulnerable yet resilient.

At Frieze’s No. 9 Cork Street, Murdoch filled the space with a densely-packed installation of these shimmering forms, a surreal banquet of objects that mimicked tools, toys, cosmetics and confectionery. Visitors were invited to come close, but forbidden to touch until the final day. This choreography of withheld contact amplified the tension at the heart of her work: one that lies on the spectrum between temptation and denial. Her sculptures request a different kind of engagement — one that is intimate, precarious, and ‘unprecious’. Designed to dissolve and transform when they no longer hold our attention, they challenge our assumptions about permanence, care, and consumption.

At the heart of her practice is a reclamation of pre-verbal, bodily knowledge: a sensual pleasure that exists before identity, language, or shame. In a world where touch is often reduced to medical, infantilised, or sexualised frames, her work insists on a non-erotic sensuality — tactile encounters that are playful, intimate, and deeply human.

In the following conversation, Sienna Murdoch reflects on her relationship with Geline, the politics of touch, and how seduction, consumerism, and failure intertwine in her slippery, gelatinous universe.

The Cold Magazine (CM): What is the genesis of Geline? What inspired you to develop your own material rather than using something existing?

Sienna Murdoch (SM): I discovered Geline through a brief for a Marvel superhero movie — that was my niche: making edible-looking things for fantasy worlds. I worked on these ostentatious, elaborate banquets for realms beyond our world. During lockdown, they asked me to make kinetic pieces for an alien banquet — they needed to move, survive on set for weeks, and look edible. It felt like an impossible brief. I passed it on at first, saying, “I’m not really a jelly person.” There was a whole jelly renaissance I wasn’t into.

But they had resources for material experimentation, so I explored biomaterials for the first time: prosthetics, bio-plastics, bio-silicone, resin. Resin seemed like the obvious choice, but it has a glass-like quality — not believably food. When I stumbled on Geline, it was like, “Oh my god, this thing is so cool, I just want to touch it.” It was easy to mold, impermanent, malleable, and recyclable — you could tear it apart, melt it down, and reuse it. That gave me such freedom, especially when materials were expensive. I became obsessed.

From there, I started making all my work out of Geline. I did a series of pies for Loki, made pieces for Bridgerton — those big jobs ended up funding a fine art practice I never thought I’d have. I began casting voids of found objects: children’s toys, wellness tools, fruit and vegetables, combining them into new forms. They were familiar but uncanny, slightly off — things you recognise but can’t quite place.

CM: As you mentioned, your sculptures are designed to melt, dissolve and transform. What draws you to impermanence and failure – and do you ever get attached to the pieces you make?

SM: I would say I feel really free; it enables me to start new chapters. I also see it as a way of sketching. People have started wanting more permanent pieces, so I’ve begun doing commissions where I ‘sketch’ in Geline and then translate them into resin or silicone. But bringing something into the world permanently feels like a really big ask — environmentally and emotionally. Do I really back this 100% to exist forever? The idea that these pieces can be melted down again just feels more exciting.

Maybe when you’re an artist you don’t aspire for your work to sit in storage or an archive. Being able to bypass that and make dynamic work feels exciting. But it’s not a protest either. I’m not putting two fingers up to the industry. It just feels playful. As a result, the work can exist in loads of different territories and applications.

CM: There’s a mischievous tension in your work — objects that dare you to touch them but tell you not to. Was that part of the fun for you? How do you want audiences to experience the tension between wanting to touch the works and being prohibited from doing so?

SM: Unconsciously, I’ve always been interested in how to make something look enjoyable to touch. What are the aesthetic principles that make you want to reach out before your rational brain can stop you? I’d never really thought about touch before, but when I did early show-and-tells with friends or curators, they’d always ask, “Can I touch them?”

I really like that tension. When Frieze invited me to do a mini-show, it felt right to honour that spontaneous interaction — even though it was scary and risky. I’d thought about having a touching room, but that felt too on-the-nose, like a weird peep show. Instead, I decided to prohibit touch until the last day, though maybe I was too prescriptive. People would come up and say, “I really want to touch them!” and I’d wonder, is that just because I said you can’t? But on the last afternoon, when people were allowed to touch them, the whole atmosphere changed. It became joyful, informal — kids running around, parents not minding, little communities forming around the plinths. People who didn’t know each other were speculating, touching the works together.

Touch engages people in a deeper, almost neurological way. It feels like a privilege if people can explore things with their fingers, investigate why they are the way they are. It was scary, though — the fear that people would figure out how I made them, see the sweaty underside I’d been trying to hide. But people didn’t mind. They were up for it.

CM: You’ve said that our language for tactile sensations is underdeveloped compared to sight. What kinds of reactions have surfaced in your touch workshops that surprised you?

SM: What initially surprised me — and now feels almost guaranteed — is that people bring up really deep memories they haven’t thought about in years. That’s very rewarding. Most of them are from childhood. Touch just goes straight to the body. Even if our language around touch is underdeveloped, it’s how we first learned about the world. When we touch things without seeing them, it takes us back to that early, sensory learning.

People also start making up words to describe what they’re feeling, or talk about how it might sound. The objects I give them don’t exist in this world — they’re fantasy objects. It’s important that they don’t make rational sense. That frees people to imagine how they were made or what their fantasy use might be.

I’ve been thinking about touch as its own sacred language, especially for women. Tactile art — like textiles — has been passed through generations of women, often uncontaminated by outside forces. Or, you could see it as women being repressed into these tactile art forms. Ancient female wisdom. I’m researching that now, including through film.

Maybe my job as a prop maker was always about bringing touch through vision — creating a haptic visual language. Making people feel more deeply immersed in a film because they can imagine touching what the characters are touching, smelling, feeling, drinking.

CM: Geline behaves in ways that are deeply sensory — trembling, sweating, slumping. Were these reactions intentional from the beginning, or did they emerge unexpectedly during experimentation?

SM: I think I was just drawn to the material. I’d love to say I designed it to express my version of the truth, but really, we met in the middle. At first, I was trying to imitate rigid objects — like shoe heels, spoons — and allowing them to droop and flop. I always imagined a spoon you’d pick up, and it would just flop around in your hand. That failure of function, turning into a sensual object, really interested me.

Geline was full of surprises. I’m always learning which of its qualities make a piece successful, and I’m still surprised by the forms I can achieve with it. I don’t think it looks like anything else. I truly believe in the fantasy of Geline — the way it refracts light is unusual. I think I’ll use it forever.

CM: As a child, were there particular materials or sensations you were obsessed with — things you think shaped your fascination with touch now?

SM: I was really drawn to glues and waxes. I also remember finding a female condom under the sink and thinking, this is incredible. I didn’t understand its use, but I knew it was fundamental in a way I couldn’t yet grasp. It wasn’t a child eroticism — more like unearthing an energy before shame. It just made sense. That sacred, uncontaminated curiosity feels important.

What I love about Geline is that it’s fragile, vulnerable, unusual — but also surprisingly resilient. You can squeeze it hard, and it pushes back. People were throwing it around, using it as swords. That’s reassuring. It’s deeply sensual and vulnerable, but it can also survive on a mantelpiece for years.

CM:If you could build an entire environment out of Geline, what would it be like? Where does it belong — in this world, or somewhere else entirely?

SM: A good friend once asked, “How can you make Geline the biggest thing in the world?” and I thought, maybe I could build houses out of it. I think a lot about objects we rely on for rigidity —spoons, structures — and how with Geline, they’d sway, vibrate, droop. I’m inherently anti-wobble, though I’ve been called a “wobbleologist” before, which I hate. But watching Geline resume its balance is seductive. Its capacity to move is special.

I imagine walls and surfaces covered in tableaus of bizarre forms — slightly recognisable but strange. You could run your hands along the grooves. I think about taking over cupboards, corridors, seeing their “asses” pressed against glass — like those sticky wall toys you throw and watch slide down. I also think about fantasy tools that pick up vibrations, tuning into frequencies. Geline exists in a real fantasy space for me.

CM: Your objects often mimic tools, toys, beauty gadgets — but resist being useful. Is that a way of commenting on consumer culture and the objects we surround ourselves with?

SM: Yeah, totally. There’s no limit to the tools you can buy on Amazon — all these little gadgets for hyper-specific needs. They’re seductive because they’re often small useless things, like gua sha tools. I love casting those kinds of objects and combining them with children’s toys.

I do think a lot about stuff — where it all goes, its physical footprint. It blows my mind that we’re not literally swimming in it. It’s sanitised so we don’t see the sheer volume, but if we did, it would be insane.

My work represents that world — by casting objects from different places, I’m not making an explicit statement, but there’s a literal commentary there. It’s about how we want to see things, consume them, shove them into our faces, into our ears. Consumer culture — how grotesque can you get?

CM: Your work embraces the spectrum between seduction and the grotesque. How do you define that balance in your own practice?

SM: I’m interested in saying something quite dark and gross through a language that looks sweet and confection-laden. I like the idea of exploiting people — drawing them in with something that mimics delicious, familiar things, only for the reality up close to feel ambiguous or even horrific. I’m curious to see how far I can push that — working with deeply unsavoury subject matter but saying it in a way that’s easy to swallow. Until you get that creeping sense of shame and realise you’re complicit in these horrors. The sweet surface disguises something much more sinister underneath.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Helen Chadwick’s Piss Flowers. The idea of casting urine tracks in snow into these beautiful flower forms — it’s humorous, subversive, serious. Humour is a big part of who I am. I’m serious about comedy. I actually just did a clown course as a palate cleanser after the show. Best thing you can do.

CM: Do you see Geline evolving further? Are you curious about exploring other materials, or is this an ongoing obsession?

SM: I have loads of questions for Geline. There are so many opportunities coming up, and I’m going to try them all and see what resonates. I’m in a very fertile, infant stage with it — being led by applying it to different ideas and seeing what sticks. I’d love for Geline to be commissioned in a site-specific way, responding to particular locations and their consumables. I also see it as a medium to work with vulnerable groups, making beautiful, sublime objects that express grotesque experiences. Things people can touch, share, and connect with physically — to help others understand something new.

It’s a way of sketching, but it could also evolve into more permanent works, or even a language I can teach to others. I’m currently working with an art director to create a suit made of it. Wearables are next. At the moment, I don’t see any limitations, which is really exciting. But fundamentally, I’m not going to sell them yet. That feels like a fun, potent tension to sit with.

In a culture obsessed with permanence and perfection, Sienna Murdoch’s slippery sculptures offer a different proposition: that beauty can lie in impermanence, failure, and the refusal to behave. Through Geline, she invites us to reconsider how we engage with objects, materials, and desires — not as static things to be owned, but as tactile encounters that resist, respond, and ultimately, dissolve.