Masculinity in the Making: A Conversation with Tiger director José María Cabral

Written by Valeria Berghinz

Tiguere – or Tiger, in its English translation – had its UK premiere during the Barbican’s Chronic Youth Festival, where it opened the programme with an unflinching look at socialised masculinity. Set in the striking mountains of the Dominican Republic, director José María Cabral confronts the deeply rooted tradition of tigueraje – a performative code of masculinity that prizes strength, cunning, and independence. Amid roaring waterfalls and dense, verdant foliage, a gothic stone residence nestles within Tiguere’s dramatic landscape – the site of a summer-long tigueraje camp run by Alberto (Manny Pérez), where young boys are hardened into men.

Tiguere follows the brutal summer in which Alberto’s 14-year-old son, Pablo (Carlos Fernández), is forcibly enrolled in the camp. As the other boys arrive and the long weeks settle in, Pablo must navigate his simmering resentment, the fragility of his own identity, and the tenuous bonds he forms with those around him. Cabral’s film offers a breathless portrayal of masculinity in formation, where the rituals of machismo – steeped in misogyny and homophobia – are relentlessly drilled into the boys under the guise of strength and survival.

In conversation with The Cold Magazine, Cabral reflected on the filmmaking process behind Tiguere – from the personal inspiration that sparked the project to the complex portrayals of masculinity that unfold throughout the narrative.

The Cold Magazine (CM): One of the things that immediately struck me about the film was its beautiful setting. The natural landscape and gothic stone residence felt like their own characters in the film. How important was this location while you were filming, and how did it inform the story?

José María Cabral (JM): The location is definitely a character in itself. It’s the kind of story that unfolds almost entirely within a single space, so the setting had to reflect a traditional idea of masculinity, especially in the way it was built, with this almost colonial architecture. But it also needed to say something about the boys’ social class. From the outside, it looks idyllic, almost perfect, but the horror begins the moment you step inside.

CM: I was really impressed by all the performances in the film. What was it like to direct younger cast members, especially when dealing with the complex topic of masculinity?

JM: I was lucky to have such great young talented actors, those kids did an amazing job. But honestly, way before filming we spent time in group discussions. We’d sit around the table, read the script together, and talk about the themes of the film. Everyone shared their thoughts and reflections, not just on the characters but on the bigger ideas. That really helped us all get on the same page.

CM: The film drew a lot of attention to the strange way that masculinity engages with sexuality. Homophobia is constantly instilled in the kids, but at the same time the social bonds they form with one another is what keeps them going. Could you tell me more about this tension and how you went about exploring it in Tiguere?

JM: Well, when you’re a teenager and you haven’t fully absorbed all the social rules about masculinity yet, what lets you connect with other people, is your ability to connect emotionally, psychologically, and physically. In Tiguere, you can see that closeness and complicity growing between the boys, but also the beginnings of bullying, probably passed down by the adults around them. We live in a world where a touch between two men makes people more uncomfortable than a punch.

CM: In addition to the way sexuality intersects with masculinity, I was also struck by the way that class and race was used to put the boys in competition with one another. Would you say these are elements that are often associated with Tigueraje, or do they reflect a more socialised version of masculinity?

JM: For sure. The kind of Tigueraje expected from a white boy isn’t the same as the one expected from a Black boy. And even then, depending on your skin color or your social class, your Tigueraje might be seen as something cool… or something dangerous. It’s a complex topic, with lots of layers and intersections.

CM: The segment of the film where Pablo and his friend leave the camp portrayed a very tender possibility for what masculinity can look like. The scenes in the rural village and on the motorbike were particularly touching – what made you want to incorporate this brief moment of freedom for the boys?

JM: I’ve always believed that no matter how hard life gets, the human spirit always finds a little pocket of freedom. That can be a sunset, a meal, a conversation with a friend, a moment of hope… and that scene in the film was exactly that. It was a moment of respect, a pause in the chaos of the camp, a chance to fly a little. In this case, on a motorcycle… but the feeling is the same: like a bird finally let out of a cage.

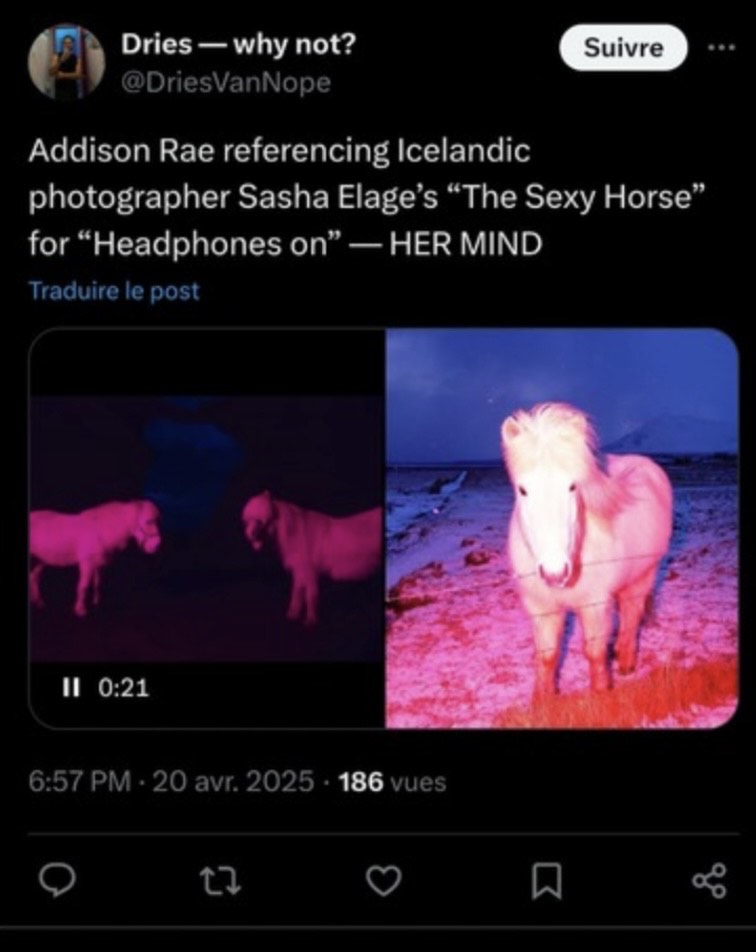

CM: The natural world and the human one seem to be in a strange and layered conversation throughout the film, especially with Alberto’s obsession with his purebred horse. Could you talk more about that dynamic, and how you saw the horse functioning thematically within the story?

JM: The horse is one of the things I least like to talk about. I try not to say much, because honestly, I think you could watch the whole film through the lens of the horse. That probably says a lot, or nothing, jaja, but I hope it’s enough to make people want to watch it.

CM: I read that Tiger is a semi-autobiographical film. Could you tell me about your experience retelling this story from your youth, and how it felt to share it both in the Dominican Republic and internationally?

JM: Yeah, my parents actually sent me to a real camp that was literally called Clase de Tigueraje. A lot of the scenes in the film are based on stuff I really went through. The one that hit me hardest and that stayed with me was when they made me fight my best friend. I was like 12 or 13, and I just couldn’t understand why I had to punch him, while the instructors laughed and cheered us on. It was brutal. Making this film felt like an act of courage from that kid who was just trying to make sense of it all.

Currently making its way through the international festival circuit, Tiguere’s next stop is the International Film Festival of Guadalajara. Dates for a wider release across Europe have yet to be announced, but it is a film worth keeping an eye on. Through Cabral’s intimate direction and the powerful performances of his cast, Tiguere’s exploration of socialised machismo reverberates far beyond the Dominican border, offering an alarming reminder of just how universal an education in masculinity can be.