Behind the Sound, Style, and Soul of the 90s Rave Scene

Written by Joshua Beutum

Edited by Lauren Bulla

Recently, raving has become a central—if slightly out-of-reach—mainstay in what it means to be young, cool, and underground. From 2000s-era raves on the outskirts of Bristol in Skins, to New York warehouse parties in Euphoria, Boiler Rooms, and the cultural moment that was Brat Summer, the last thirty years have seen a steady proliferation of the scene—its sound, its fashion, its energy.

But in an age where the aesthetics of the party seem almost as relevant as the community behind them, it’s important to pay our dues to the trailblazers who came before us—the founders of an iconic scene who innovated with fewer resources, fewer safeguards, and a good dose of social pressure.

The latest offering from archive-bookstore-turned-publishing-house IDEA Books does just that.

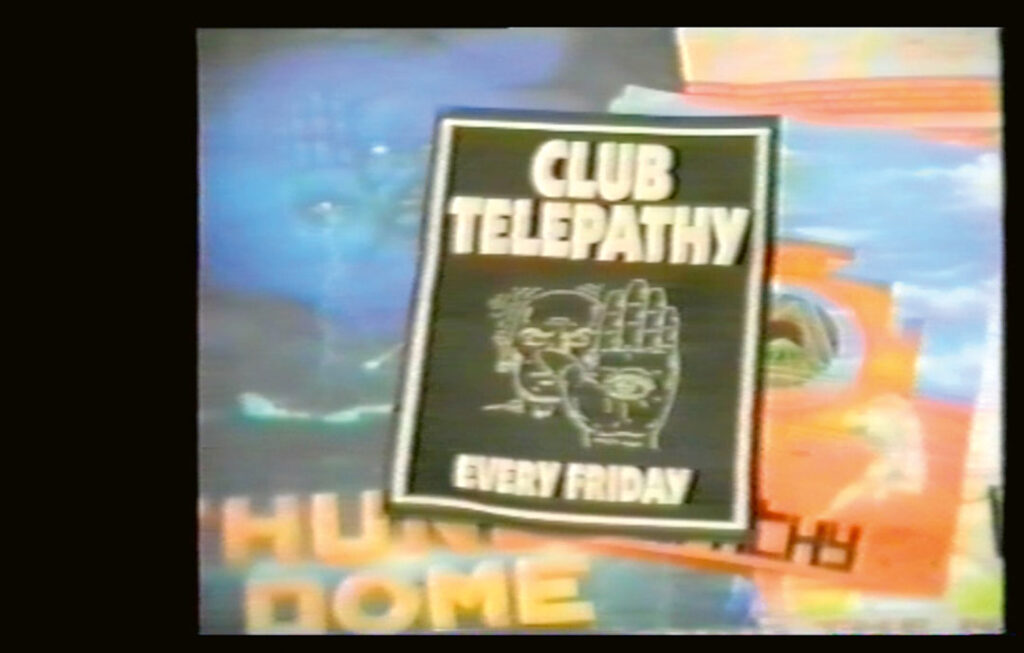

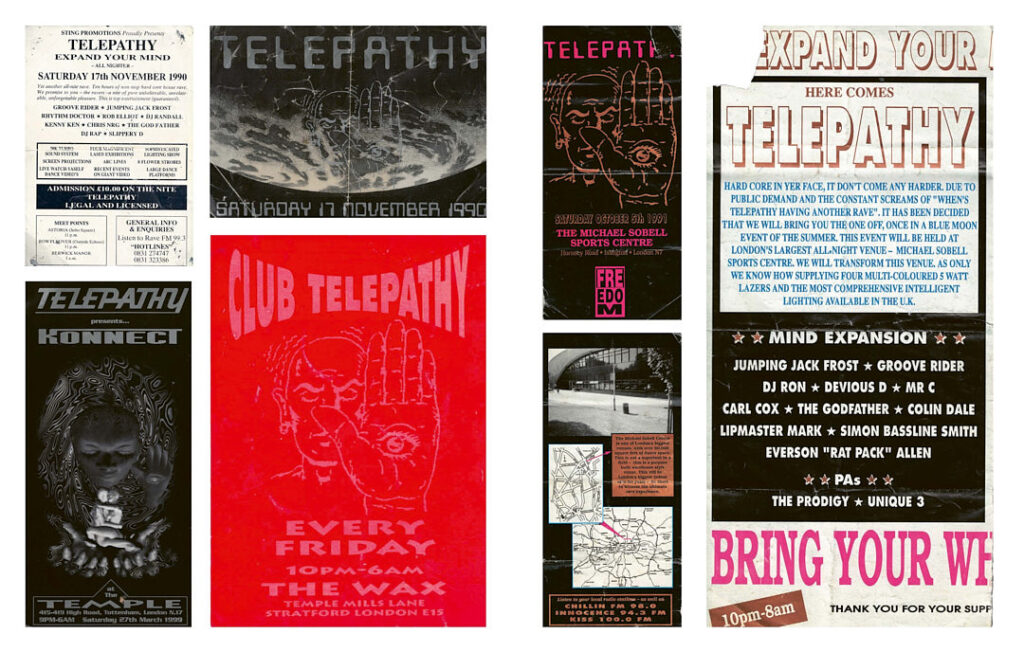

In STEP IN TIME, curators Andrew Bravin and Rollo Jackson offer a rich glimpse at the Hardcore and Jungle scenes at Life Utopia and Telepathy, as well as the life of their legendary founder, Sting (Kenny King). In an odyssey through unseen flyers, VHS stills, and—most impressively—interviews with Andy C, Funk Butcher, and Sting himself, they shed light on the politics, community, and sound of the 90s.

Speaking with Sting, it’s clear the purpose of STEP IN TIME is to communicate the social dynamics behind the sound. ‘It was about breaking down barriers and social interaction,’ he tells me of the early rave scene, ‘the powers that be spent every ounce of their energy trying to divide us, but we wouldn’t be divided.’ At his raves, a stockbroker, a city slicker, and a club kid could dance side by side, united by the throb of the music and what he describes as the ‘hypnotic, addictive, social scene’—a moment that was, as Jackson stresses, owed in no small part to the contributions of Black artists like Sting.

‘There’s also a layer of social commentary about what putting on music was like in that era,’ Jackson reflects when asked about the political implications of the rave, about ‘how people of different backgrounds did and didn’t mix, and how music did make a big difference to changing those habits.’

In a climate marked by stark class divisions and political unrest, Sting’s raves were about more than an aesthetic or genre, but a full-scale social revolution. Reflecting on Margaret Thatcher’s 1987 argument that ‘there is no society, only individuals,’ Sting tells me that the rave ‘was the complete opposite’. It was a site where all walks of life came together in a great mixing pot of late-night music.

This community is a far cry from what Sting describes as a ‘certain type of people, posing or being there to be seen’ at some of today’s parties. In fact, he jokes, these events are not raves at all: ‘You may as well stay at home in your bedroom and rave in front of the mirror if you’re going to do that.’

But the value of community at Life Utopia and Telepathy cannot be overstated. Sting goes as far as to attribute the birth of genres like Acid House and Garage to the dynamic between DJs in scenes shaped by spontaneity, improvisation, and friendly competition. There were no ‘ready-made’ categories, but moments of experimentation and serendipity onto which labels were later imposed.

As Sting tells me, Grime—a type of electronic music combining Jungle and Garage—came into being because of the politics of scheduling and a social hierarchy among DJs and MCs. In fact, it’s almost funny to think an entire genre whose influence has reached as far as the likes of Skepta and Stormzy began when MCs who couldn’t get slots on the Jungle sets ended up in the Garage room.

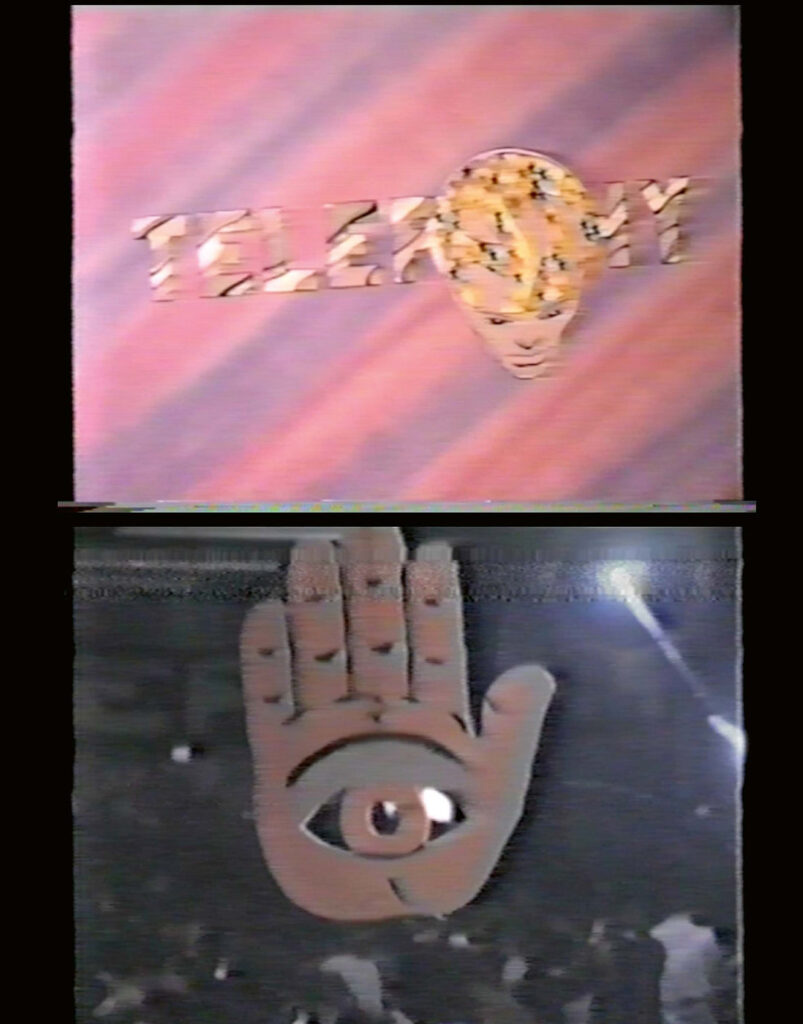

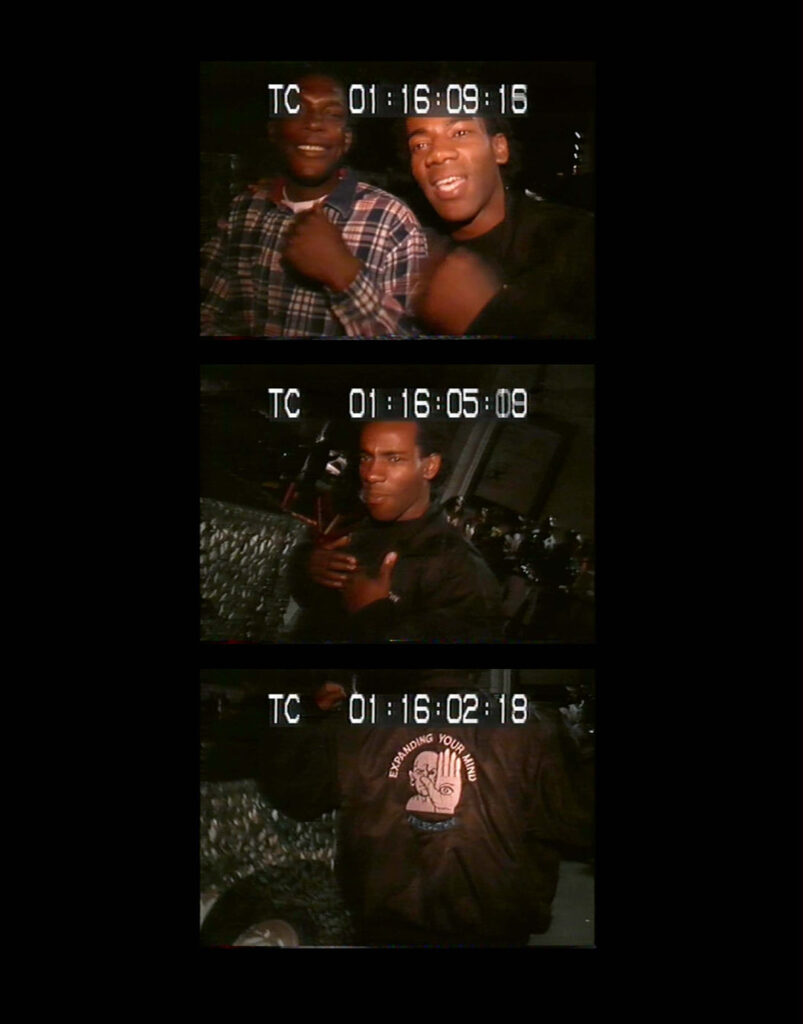

While it’s undoubtedly a comprehensive insight into a scene whose members have often chosen to veer away from the limelight, STEP IN TIME is, beyond that, visually stunning. With bright colours, blurry crowds, hallucinogenic flyers, and a recurring raised hand synonymous with the Telepathy club, it feels like a living, breathing piece of the scene—an embodiment of the rebellious style of the time.

According to Jackson, this authenticity stems from the fact that ‘it’s pure documentation: a lot of the imagery is made without prejudice, without being self-conscious.’ To his point, the VHS stills depict moments from whole scenes, not individuals posed in forced positions, and the many flyers represent an organic, almost unfiltered look into the visual language used to promote Sting’s events. What results is a journey that feels, in Jackson’s words, ‘otherworldly, but not remotely contrived.’

Perhaps this is because STEP IN TIME positions rave culture as a dynamic movement expanding well beyond the confines of noise. ‘I have to give tremendous respect to IDEA Books,’ says Sting, ‘It wasn’t so much about documenting a sound as documenting a social explosion that was expressed by sound, dancers, and fashion, and reflected in a new medium with real visual impact’. Either way, what results is an immersive adventure through the UK rave scene in the 80s and 90s.

The project is unsurprisingly popular—the first edition sold out before it was even printed. Now, reflecting on the much larger audience eagerly awaiting the second edition, Sting and Jackson are clear. It’s not so much about creating a publication catering only to scene-veterans but about giving non-ravers an important glimpse into a cultural turning point. As Sting says, what STEP IN TIME proves is that ‘you don’t have to have been there to capture the essence of this thing called RAVE!’

STEP IN TIME is available now at IDEA BOOKS, in-store and online.