The Genealogy of the Bed in Contemporary Art: From Intimacy to Public Provocation

written by Ritamorena Zotti

The bed, which represents rest and intimacy in everyday life, has undergone a drastic alteration in the artistic sphere over the years, redefining the boundaries of the private and the public. The bed has evolved from a simple household object to a powerful symbol that reflects the tensions between personal intimacy and social criticism, as well as the drama of human existence. Analysing works that employ the bed as both subject and object reveals not only its aesthetic and symbolic value, but also the complexity of human beings in relation to their surroundings.

The Perspectival Bed as Figurative Revolution: Andrea Mantegna’s “Lamentation of Christ”

Andrea Mantegna’s Lamentation of Christ (c.1480) is a work with a strong visual impact. The work represents a use of perspective on the figure of Christ and has the strange quality of “following” the observer as they move around it.

Almost all the space of the painting is occupied by the figure of Christ lying on a reddish, bed-like tombstone. This helps to focus attention on the anatomical details: the wounds left by the nails on his feet and hands, the swollen chest, the abandoned head. The body is wrapped in a shroud, while at the end (on the right) you can see the ointment jar, used to sprinkle oils and essences on Christ’s corpse before burial. He thus takes on a monumental dimension in an image of intense drama.

Before Mantegna’s Christ, the Son of God had never really been depicted in such a concrete and material dimension. Mantegna made bold use of perspective, adopting the foreshortening technique, so called because it “shortens” the figures, accentuating the perspective effect to the maximum, revolutionising representation in figurative art. The depiction of Christ lying down further revolutionises the mode by shifting the focus to the physicality and vulnerability of the human form, breaking away from traditional, idealised representations of Christ. This daring composition integrates perspective and emotion, transforming the act of lying down – albeit on the deathbed, in this case – into a focal point of artistic and spiritual involvement.

A Bed of Defiance: Edouard Manet’s “Olympia”

A young naked woman is lying on a bed facing the front of the painting. Her face reveals no emotion and her sharp gaze is directed forward. The protagonist is wearing only a few jewels, pearl earrings and a bracelet. Her left arm is bent and supports her torso, while her right hand covers the girl’s pubic area. Next to her, a black cat, an erotic symbol linked to female sexuality, raises its tail. The mattress is covered with a crumpled white sheet while large pillows support the young woman’s torso.

The setting is minimally described and very sober. In his painting, Olympia, Edouard Manet proposed a new interpretation of the female nude, a genre belonging to the tradition of Western painting. In fact, the artist resorted to a direct representation without compromises with the bourgeois morality of the time. The central figure, a prostitute, is therefore represented in a prosaic way without veils; she is shown physically, and with a crude language. Instead of the idealised nude of high art, Manet proposed a cold and realistic image of a young courtesan. Her figure is not revisited with mythological, allegorical or symbolic filters but represents only a naked prostitute. Indeed, the pose that classical tradition assigns to Venus is here intended for the representation of prostitution. Manet’s bed thus becomes a space of defiance.

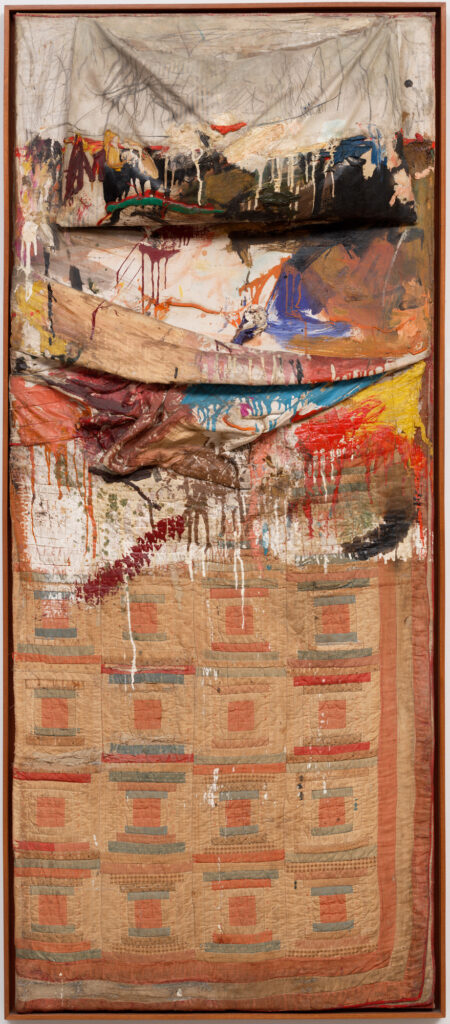

The Bed as Canvas: Robert Rauschenberg’s “Bed”

Bed is one of Robert Rauschenberg’s first and most well-known combination paintings, blending items and colours in compositions that cannot be strictly classified as pictorial or sculptural. It is, in reality, a genuine bed staged with a mattress, sheets, checkered blanket, and a pillow, suspended vertically from the wall and “dirtied” with colour. The work is considered a manifesto of new dada poetics since it demonstrates for the first time, in a blatant and surely offensive manner, the elevation of the common object, in its original materiality, to the status of a work of art. The image, which maintains the painting’s identity, is actually a “sample” from everyday life, unlike Mantegna’s and Manet’s representations.

The bed is not, in fact, just an imitation of itself, but a bed in all respects. And it is even “used”, unmade, stained to the point of increasing the impression of authenticity in the viewer. The author’s intention is therefore to make the public meditate on the thin threshold that separates painting from its subject, the truth of fiction. Color is used here as a binder: in fact, the traces of dripped paint add something lived-in and, at times, dramatic to the crumpled sheets.

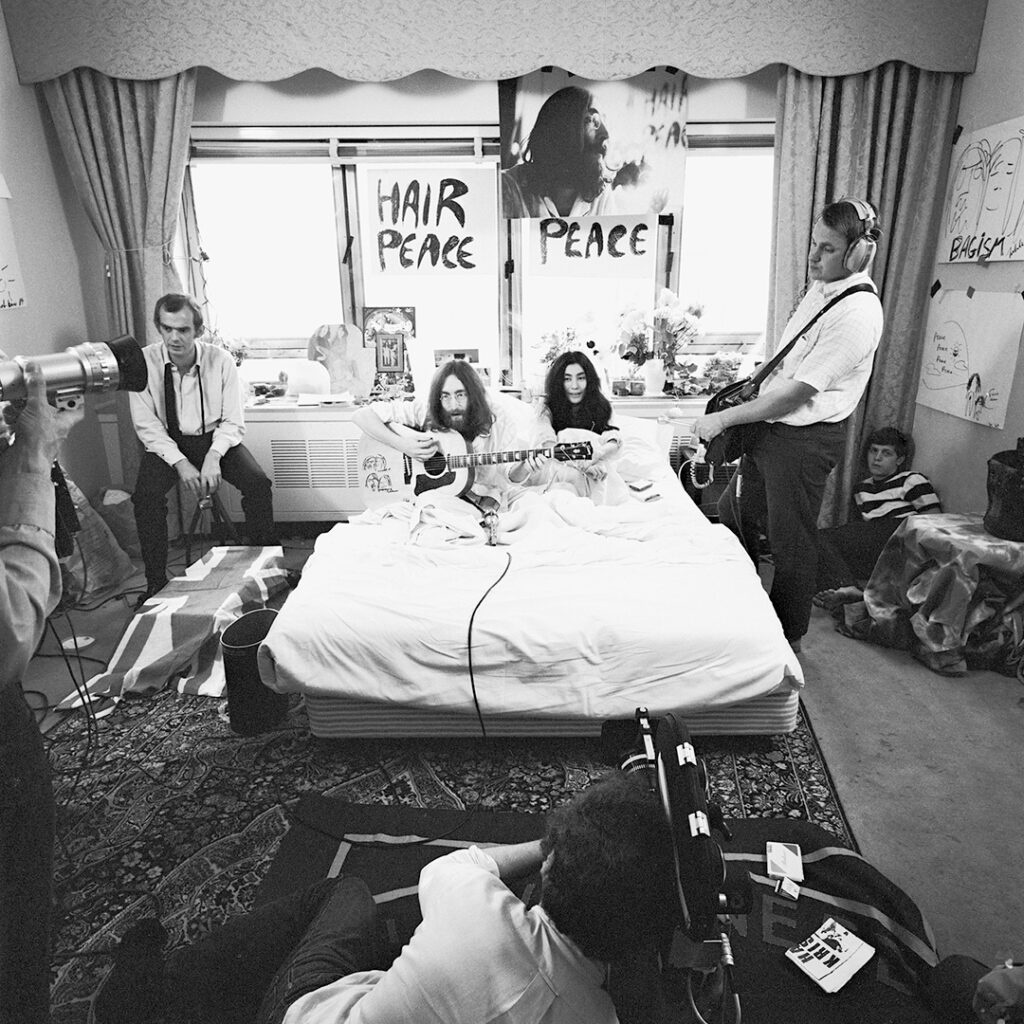

Activism and Intimacy: Yoko Ono’s “Bed-In”

With their iconic Bed-In (1969), Yoko Ono and John Lennon reconfigured the bed as a stage for political activism. During this performance, the bed, the quintessential site of intimacy, became a symbol of pacifist protest against the Vietnam War. In an act of extraordinary simplicity, the couple merged the personal and the public, transforming the everyday into an act of resistance.

Rooted in the practices of the performance art of the 1960s and Fluxus, a Latin term meaning flow, (a phenomenon in continuous change, which has neither form nor place), it promotes the idea of a hybrid art, in search of new tools that relate it to life and allow a broader understanding through the symbiosis between various expressive forms and between reality and artistic creation. The work reflects the revolutionary potential of the private.

Bed-In is a declaration that demonstrates how even the most private gestures may have political consequences, putting the bed at the heart of a discussion about the potential of a future based on ideals of peace and understanding.

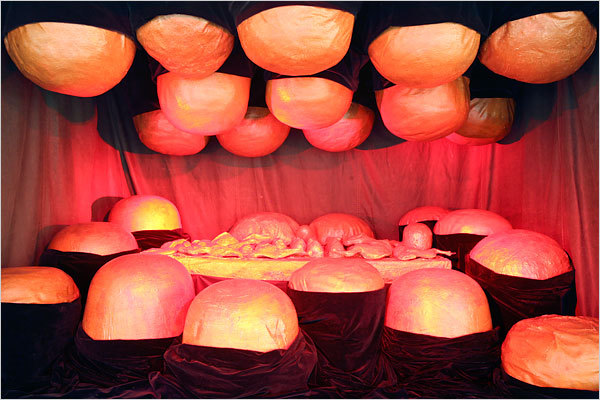

The Bed as Theater of the Psyche: Louise Bourgeois

For Louise Bourgeois, the bed is a site of psychological tension and repressed memory. In works like The Destruction of the Father (1974), the artist deconstructs the bed’s form, transforming it into a disturbing sculpture, an interior landscape where familial conflicts and childhood traumas collide.

This reinterpretation recalls Freudian psychoanalysis and surrealist aesthetics, where the bed becomes a metaphor for the unconscious. Bourgeois uses the bed to explore the duality between comfort and threat, rendering it a symbol of unresolved familial dynamics. Her work intersects with the feminist movements of the 1970s, which sought to deconstruct gender roles tied to domesticity, revealing the bed as a space both intimate and imbued with oppression.

Minimalism and Absence: Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled (Bed)”

Félix González-Torres’ approach to the theme of the bed is distinguished by a poetics of simplicity and quiet melancholy. Untitled (Bed) depicts an empty, impeccably arranged bed, whose palpable absence evokes mourning for the artist’s partner, lost to AIDS. In this work, the bed transforms into a universal symbol of loss and impermanence, speaking both of intimate grief and collective tragedy.

Rooted in the minimalist and conceptual traditions, González-Torres uses the aesthetics of absence to suggest presence. The bed, motionless and silent, invites the viewer to reflect on the impermanence of love and the fragility of life within a historical context marked by the devastation of the AIDS epidemic. This work, though simple in form, possesses an emotional depth that transcends the personal to embrace the collective.

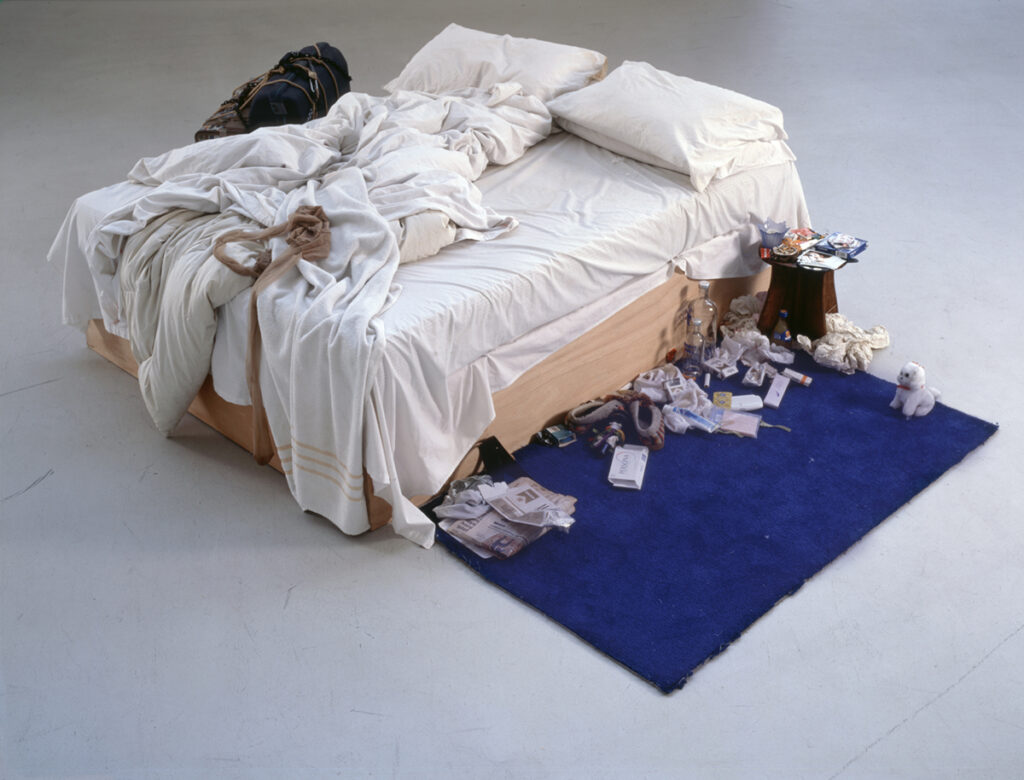

Confession and Chaos: Tracy Emin’s “My Bed”

In My Bed, Tracey Emin elevates the bed to a symbol of autobiographical confession. The work, which depicts an unmade bed surrounded by intimate, disordered objects – empty bottles, cigarette butts, stained sheets -, offers an unflinching portrait of human vulnerability. Emin does not conceal the emotional turmoil behind the scene but exposes it as a manifesto of the postmodern condition. Situated within the feminist practices of the 1990s, the work challenges viewers to confront the fragility of existence, often relegated to silence. The bed, once a place of rest, thus becomes – like it was for Bourgeois – a psychological battleground, a space where the tensions of identity and personal suffering intertwine with broader reflections on the precariousness of contemporary life.

Memory and Displacement: Do Ho Suh and Chiharu Shiota

Do Ho Suh and Chiharu Shiota introduce a transcultural perspective to artistic discourse, reflecting on identity and memory through the figure of the bed. Suh’s installations, such as Home Within Home (2013), recreate childhood spaces – including the bed – using transparent fabrics that evoke the fragility of memory. This work explores the migrant condition, where the bed becomes a symbol of a portable home, an intimate presence that transcends geographical boundaries. Shiota, on the other hand, envelops beds in intricate webs of thread, creating emotive scenographies that speak of connection and loss.

The threads, evocative of memory and destiny, transform the bed into a network of collective bonds and traumas, resonating with the Japanese philosophy of impermanence. Both artists reinterpret the bed as a symbol of identity in flux, where the soul meets the outside.

Conclusion: The Bed as an Archaeology of Being

Through the works of these artists, the bed emerges as a powerful polysemic symbol, capable of synthesising intimacy and universality, introspection and social engagement. From a space of rest to a site of conceptual inquiry, the bed manifests as a mirror of the human condition, reflecting our fragilities, memories, and aspirations.

In tracing this genealogy, we see the bed transform into an archive of our being, a microcosm intertwining individual lives and collective discourses. The bed, from a mere functional object, reveals itself as a platform for art, a site of inexhaustible meanings, capable of speaking to us today with its enigmatic depth.This genealogy not only deepens our understanding of the bed’s role in contemporary art but invites us to consider its reception through the lens of cultural shifts, psychological exploration, and political upheaval.

It is through this lens that the bed, ever mutable, becomes a profound reflection of the complexities of human existence.