Viennese Actionism: Blood, Body, and Ritual in Contemporary Art

Viennese Actionism emerged in 1960s Austria as a radical response to the cultural repression following Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany in 1938 and the country’s involvement in the Holocaust. It made the body a medium to transgress societal taboos through extreme performances steeped in blood, self-mutilation, and sacrificial rituals. Figures like Günter Brus and Hermann Nitsch pushed the boundaries of the physical and the moral, creating visceral works that resonate in the contemporary practices of artists such as Marina Abramović. Performances like Rhythm 0 (1974) made the body a sacred site of vulnerability and collective confrontation. Abramović’s current acclaim testifies to the enduring influence of Actionism, devoted to exploring corporeality, ritual, and the ethical dimensions of artistic provocation.

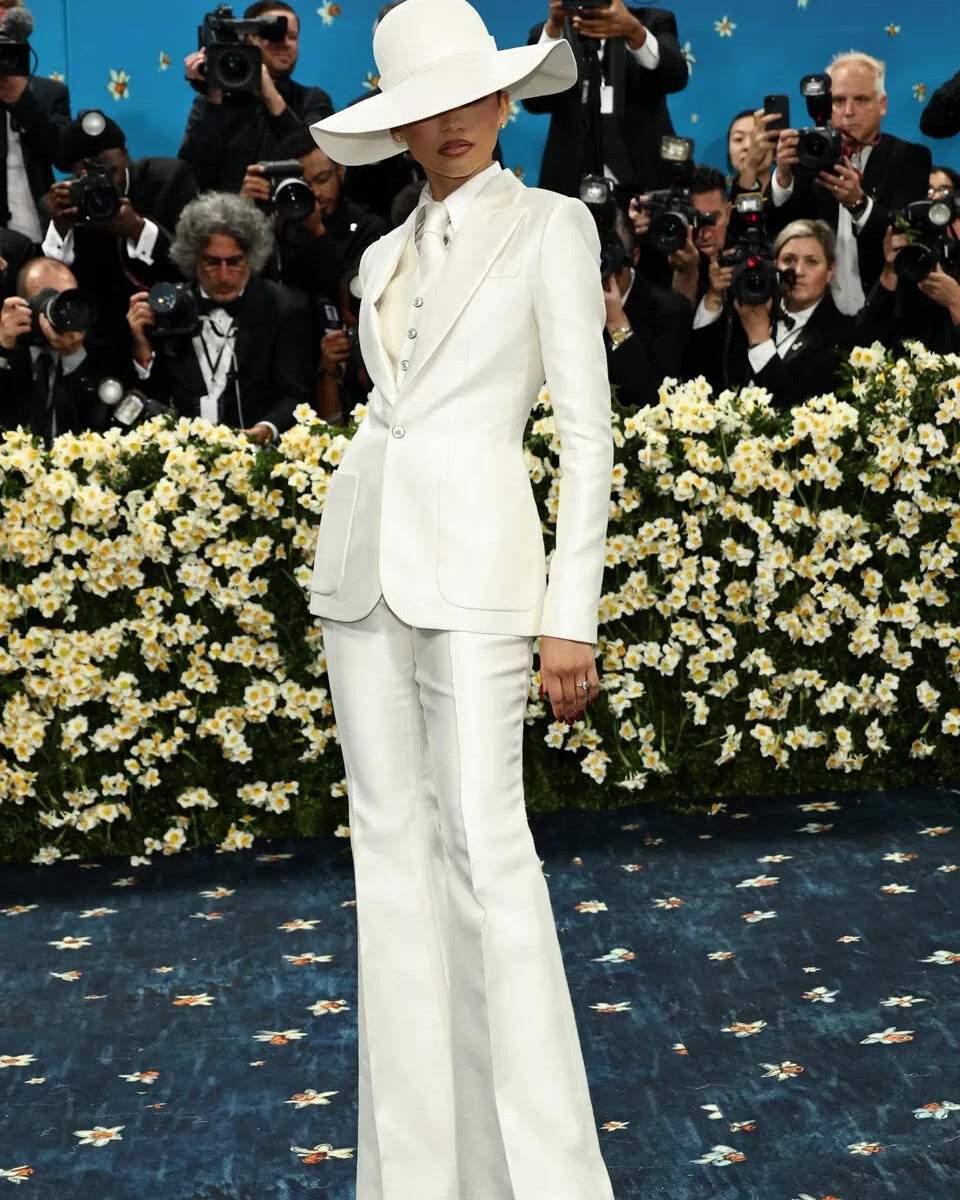

Caption: Hermann Nitsch, 20th painting action, 1987, Secession, Vienna. © Hermann Nitsch. Photo: Heinz Cibulka

To fully understand the significance of Viennese Actionism, it is essential to examine the artistic and cultural norms the movement sought to overturn. In post-war Austria, artistic production clung to traditional forms. This was epitomised by the Vienna School of Fantastic Realism (Wiener Schule des Phantastischen Realismus), a movement that fused the meticulous techniques of Renaissance painting with dreamlike, mythological, and spiritual themes, offering an idealised vision far removed from harsh reality. Similarly, mainstream Austrian theatre reflected a bourgeois, sanitised taste, avoiding any confrontation with the historical traumas and moral responsibilities tied to Austria’s Nazi past.

Against this cultural and artistic backdrop, the Actionists, including Günter Brus, Otto Muehl, Hermann Nitsch, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler, launched their vehement rebellion. They rejected the symbolic and escapist tendencies of Fantastic Realism, instead embracing a direct language in which the body and its physicality became the primary means of exposing suppressed truths and deep wounds. The canvas was abandoned in favor of an “art-making” that employed blood, excrement, and the human form itself, transforming art into an immediate and unsettling experience.

The ephemeral roots of performance art resist commodification thanks to hic et nunc (here and now), that is, to exist only at the exact moment when an action happens.The traces of performance cannot replicate the original experience thus challenging the traditional art markets based on ownership and trade. The rejection of institutional spaces creates consensus towards unconventional actions, which by nature are against the capitalist structures that govern cultural production.

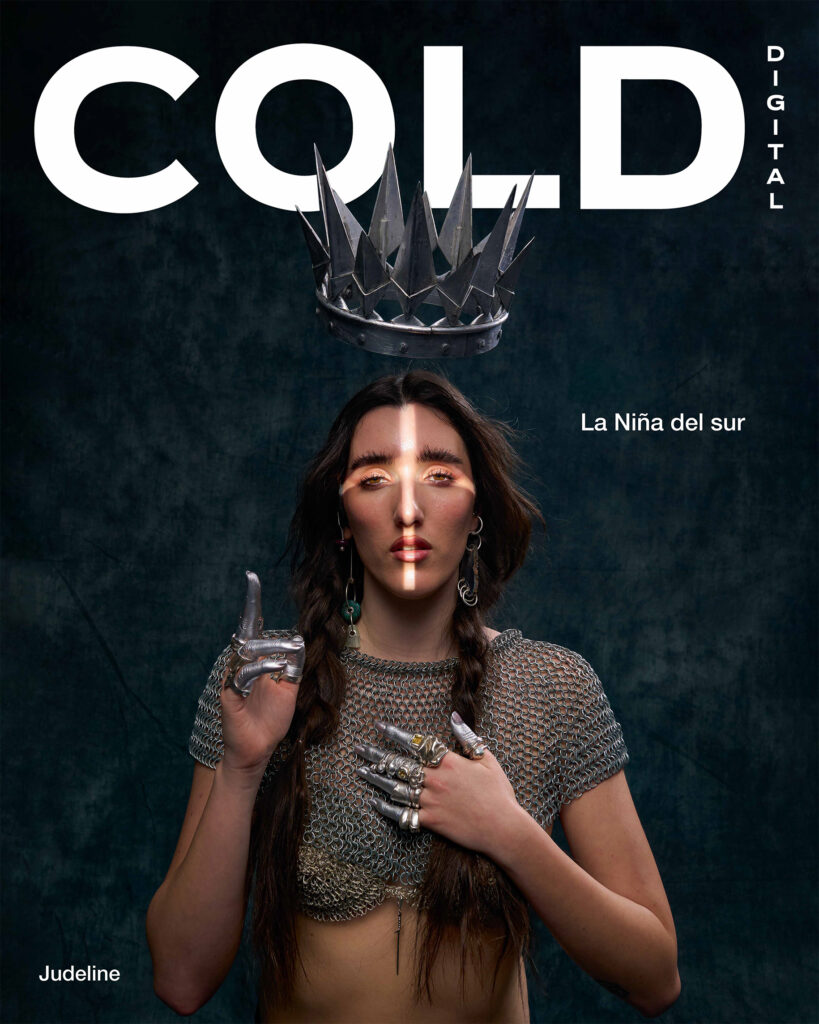

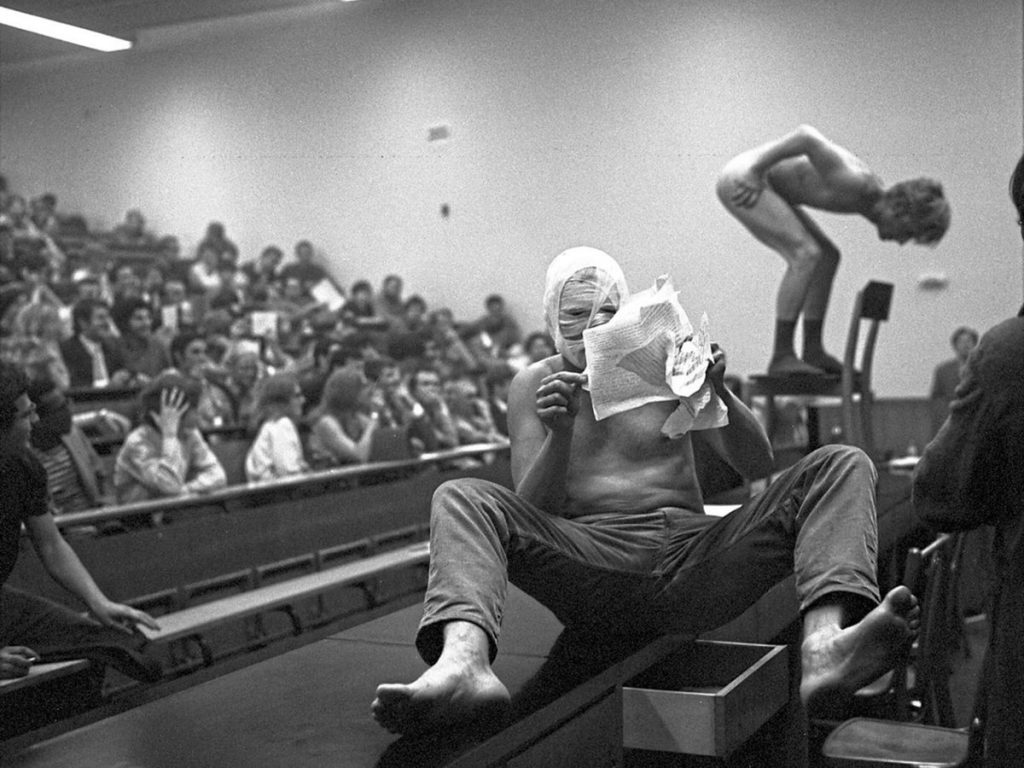

Günter Brus and Otto Muehl, Kunst und Revolution (Art and Revolution), 1968, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. MQW. Retrieved from Daily Art Magazine.

The Birth of Viennese Actionism: Context and Provocation

Through this rupture with artistic and societal conventions, Viennese Actionism positioned itself as an act of defiance, unveiling the silence surrounding historical complicity and reframing art as a tool for collective exposure and catharsis. Blood, in particular, holds a uniquely dual symbolism in Viennese Actionism. As the literal essence of life, it connects the individual to a primal, collective experience while also emphasizing mortality and fragility.

In a post-war era marked by physical and emotional trauma, blood transformed the body into both a battleground and a temple. This metaphorical “theatre of cruelty”, a concept created by Antonin Artaud in the 1930s, aimed to go beyond traditional theatre based on dialogue and realistic representation. The foundations of Artaud’s artistic vision aspired to a theatrical experience that would profoundly engage the audience’s body and senses, employing acts of violence and ritual to delve into elemental themes such as death, existence, and memory. His purpose was to awaken a visceral, primal emotional response, compelling the spectator to confront the most harrowing and universal truths of the human condition.

Hermann Nitsch famously explored this theme in his Orgien Mysterien Theatre (1960-1987), an ambitious and controversial project conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total artwork”, that merged visual art, music, and ritualistic performance. This expansive series of actions involved participants engaging in visceral ceremonies using blood, animal organs, and religious iconography to confront primal emotions and reach a state of catharsis. Nitsch sought to dissolve the boundaries between art and life, sacred and profane, evoking profound existential reflection through sensory overload. The performances often unfolded as theatrical rituals, replete with chanting, processions, and sacrificial imagery, drawing on archetypal themes of death and rebirth

Hermann Nitsch, Orgien Mysterien Theatre, 1950s-1960s. Nitsch Foundation. Retrieved from Daily Art Magazine.

In the 45th Aktion, staged in 1974, Nitsch presented one of his most intense enactments of this vision. Set in a carefully orchestrated environment, the performance featured participants and objects drenched in blood, alongside disemboweled animal carcasses. Music composed by Nitsch himself heightened the emotional impact. The ceremony unfolded as a structured yet chaotic spectacle, with participants performing gestures that evoked both religious liturgy and primal instinct. This Aktion immersed the audience in a layered experience, where the raw physicality of the materials juxtaposed with the metaphysical questions it posed about morality, mortality, and the nature of ritual itself. His approach suggested that art is not merely to be observed but experienced—physically, emotionally, and psychologically.

For Gunter Brus and Otto Muehl, the body was a canvas on which to inscribe social and psychological conflicts. In Körperanalyse (Body Analysis), Brus presented a series of self-harming actions that exposed his own body to pain and vulnerability. His works were deeply personal acts of rebellion, pushing against societal repression and reflecting his belief that authentic art must confront and express raw human experience. Rudolf Schwarzkogler, another significant figure in Actionism, took this concept further in his staged photographic series, such as the 3rd Aktion (1965), in which he explored bodily mutilation through ritualised gestures. These works used the body as a sacrificial site, a harrowing critique on the commodification and consumption of the self, pushing the boundaries of acceptable aesthetics to highlight the human cost of conformity.

Why Viennese Actionism Still Resonates Today

In an era of hyper-consumerism and image-saturation, the raw, unfiltered approach of Viennese Actionism remains deeply relevant. Its insistence on the body as both medium and message has inspired countless artists to explore themes of authenticity, vulnerability, and mortality. In confronting their audience with intense, often uncomfortable experiences, Viennese Actionists demanded a level of emotional engagement that challenges the passive consumption of art. Today, as we grapple with new forms of social and personal alienation, the works of Nitsch, Brus, Muehl, and Schwarzkogler serve as reminders of art’s power to confront and transform human suffering. Their legacy endures not only in the materials and themes of contemporary artists but also in the ongoing debate over the purpose and boundaries of art itself. Viennese Actionism, with its fusion of blood, body, and brutality, continues to push us to consider: how far must art go to reveal the truth of the human condition?

Piotr Pavlensky, with his performance Nailed Testicles (2013), embodied the sublimation of physical pain into an act of political resistance, distilling the human experience of agony into a subversive and universal language. By nailing his genitals to the cobblestones of Moscow’s Red Square, the artist does not simply engage in an act of self-mutilation, but rather performed a ritual of extreme violence against himself, symbolizing the paralysis of the individual under the yoke of a totalitarian regime. This act, often interpreted as a form of self-destruction, was in fact a radical form of resistance that challenged oppressive structures through the body itself, which became not only the vehicle of suffering, but also the medium for a collective protest that transcends the limits of

Piotr Pavlensky, Nailed Testicles, 2013. Photograph: Reuters.

This reflection on pain deeply intertwines with the theories of Elaine Scarry, who in her seminal work The Body in Pain (1985) explores the ways in which pain challenges the limits of language, reducing the symbolic capacity of the human body and making it captive to its own suffering. Scarry argues that pain annihilates the linguistic structure, depriving the individual of any form of communication and trapping them in a world made only of silent screams, spasmodic gestures, and tearing. In such a condition, the experience of pain seems to escape traditional means of representation and symbolism, making it impossible to transmit an agony that refuses to be translated into words. However, in Pavlensky’s bold act, pain becomes a public language, transcending the ineffability described by Scarry. It is no longer confined within the interiority of the suffering body, but emerges as a declaration of political existence, capable of awakening collective awareness and responding to its suffering with visible, tangible, and unsettling protest.

The radical use of blood and bodily harm as mediums in art opens profound ethical and philosophical questions about the role of suffering when it is brought into the public eye as part of a staged experience. When artists confront audiences with images of bodily fragility and suffering, they challenge the viewer to grapple with discomfort, empathy, and perhaps even a sense of complicity. Such works provoke a layered response, urging us to examine our own limits as witnesses to human vulnerability and to question what it means to create a shared space for reflection on life’s rawest truths. This deliberate confrontation, often unsettling, raises an essential inquiry: where does art’s pursuit of emotional impact intersect with our ethical responsibility as observers of another’s pain? How far can art go in order to strike a human chord? And what does it mean, ethically, to expose the body’s vulnerability to provoke viewers?

These works connect to the Heideggerian concept of In-der-Welt-sein, being-in-the-world, which highlights the tension between the innermost desires of the individual and the social expectations that shape them. Here, the body becomes both theatre and battleground, a place where struggles between vital impulses and the constraints imposed by culture and collective morality manifest. The shocking performances of the Viennese Actionists remind us that art can be raw, frightening, and untamed—a medium that shakes us out of our comfort zones to reveal, through blood and flesh, a humanity capable of reflecting our common journey of suffering and understanding.